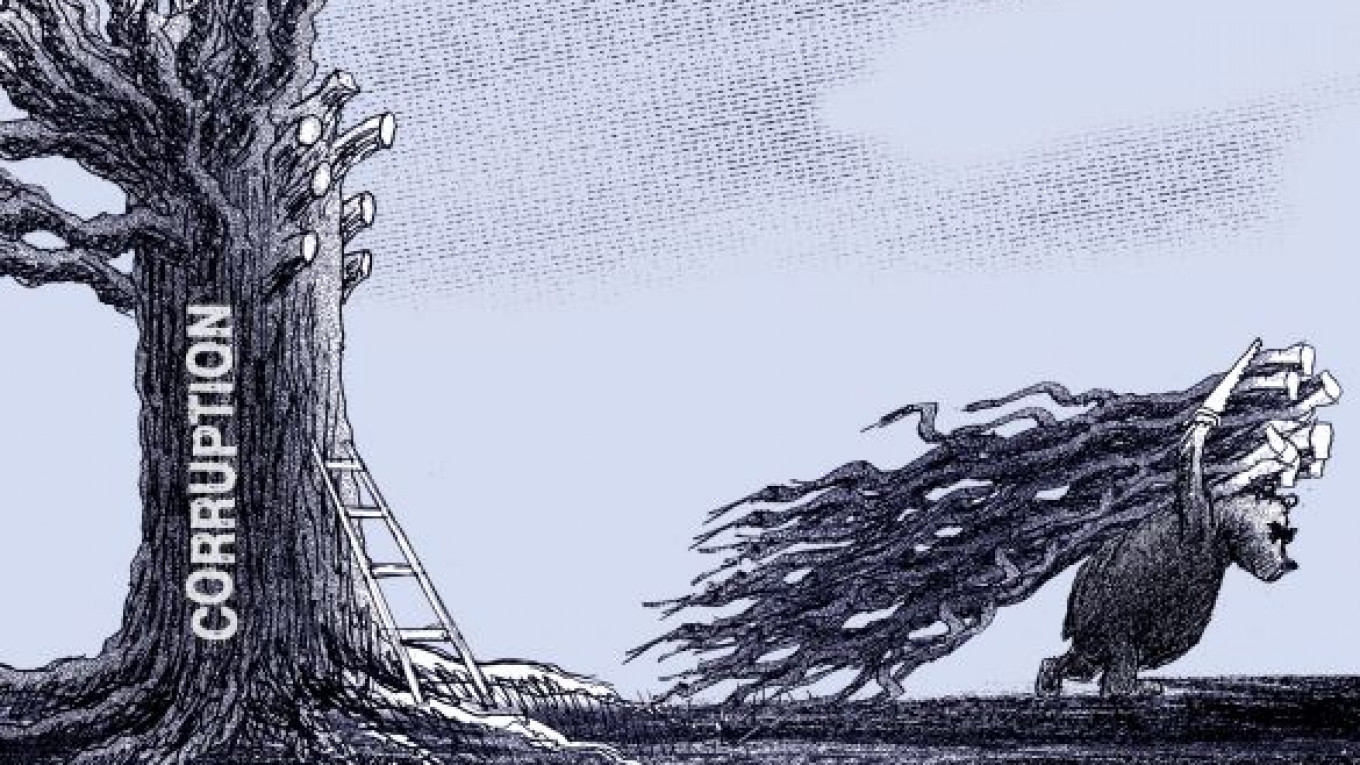

Commenting on Russia's enormous problem of corruption several years ago, then-President Dmitry Medvedev tried to put a positive spin on the issue, saying that all countries are corrupt and that the real problem for Russia is one of perception rather than reality.

Yet most foreign businesses have taken a much different view on the subject. Surveys conducted among foreign investors have consistently shown that corruption matters enormously in the decision to invest in Russia or increase the scale of existing operations in the country.

While Rosstat, the state statistics service, calculates that corruption amounts to between 3.5 percent and 7 percent of gross domestic product, most independent estimates hover around the 25 percent mark and higher. Furthermore, there appears to have been a marked increase in corruption during President Vladimir Putin's second presidential term, from 2004 to 2008, which was a period of economic boom in Russia.

The current anti-corruption campaign shouldn't be dismissed as cheap PR. There is now a real, high risk of being caught.

Yet the anti-corruption campaign initiated in 2008 and bolstered since Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 has morphed into something more than simply a campaign directed at cleaning up the business environment.

Most Russians are skeptical about these state campaigns, seeing them as little more than a smokescreen to deflect attention from corrupt officials. What's more, a number of lawmakers have turned on each other, fueling the perception that the anti-corruption campaign has unleashed a political free-for-all aimed primarily at settling personal scores.

But it would be wrong to dismiss the campaign as cheap public relations. The scale and the high status of some who have been exposed, including former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, has suggested that those using public money for private gain face a genuine risk of being caught. In addition, there have also been investigations regarding plagiarism in the academic community; embezzlement in state corporations and ministries; fraud in the prison service; tax evasion by companies and high-profile individuals; fraud in state tenders and purchases; and corruption involving contracts for the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

The largest problem for foreign investors is that very little of this is connected with the business environment. There has always been an awareness among the elite that Russia needs to take these steps if it is to secure large investments that are needed to modernize the country. But there are serious doubts about the ability of the anti-corruption campaign to do this.

The targeting of state-owned companies and public officials underscores the notion that corruption in Russia is a top-down phenomenon that manifests itself as a bottom-up operating issue. A civil servant needs to meet the target set by his superior, who in turn must meet a target for his own superior and so on up the chain. Ironically, the fact that the average bribe has increased in size over the past decade provides some good news: It means the risk of taking a bribe has also increased.

At both the federal and the regional levels, a spate of new guidelines and laws is being enacted to crack down on the large-scale theft and corruption. For example, the city of Moscow has received praise for its overhaul of tender processes in a bid to promote greater transparency, and some regional governments are following suit. State-owned power companies are now forbidden from contracting companies with unknown ultimate beneficiaries.

Recent high-level arrests have shed light on the companies and schemes involved in the misappropriation of state funds, many of which have involved fixing tenders, false invoices and illegal payments to offshore accounts. The expectation is that new anti-corruption measures will reduce the opportunity for officials to seek bribes, as doing so would become prohibitively risky. In the meantime, foreign companies operating in Russia should be mindful that despite the rhetoric of the current anti-corruption campaign, in many day-to-day interactions a request for unofficial payments remains a common part of the country's business culture.

Foreign businesses encounter corruption most often when government contracts and state purchases are involved, or when these companies try to obtain permits or clear customs. Especially small- and medium-size businesses are often stuck between the need to get their products into the country and the necessity to act within the limits of the law.

To enforce a zero-tolerance policy on corruption, employees need to be well-trained, adequately remunerated and well-trained on corporate ethics policies. Visibility over their operations is often the most important weapon in battling corruption. Understanding the political and commercial nuances in the region in which they operate is also a key element. Local governance in Russia's regions varies enormously, and the federal government's anti-corruption message may not have filtered down to the region of operations. Perhaps most important, companies need to hire and retain trusted employees — particularly in roles susceptible to corruption — such as procurement and government relations.

Steven Eke, Rosie Hawes, and Hannah Lilley are consultants at Control Risks, a global risk consultancy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.