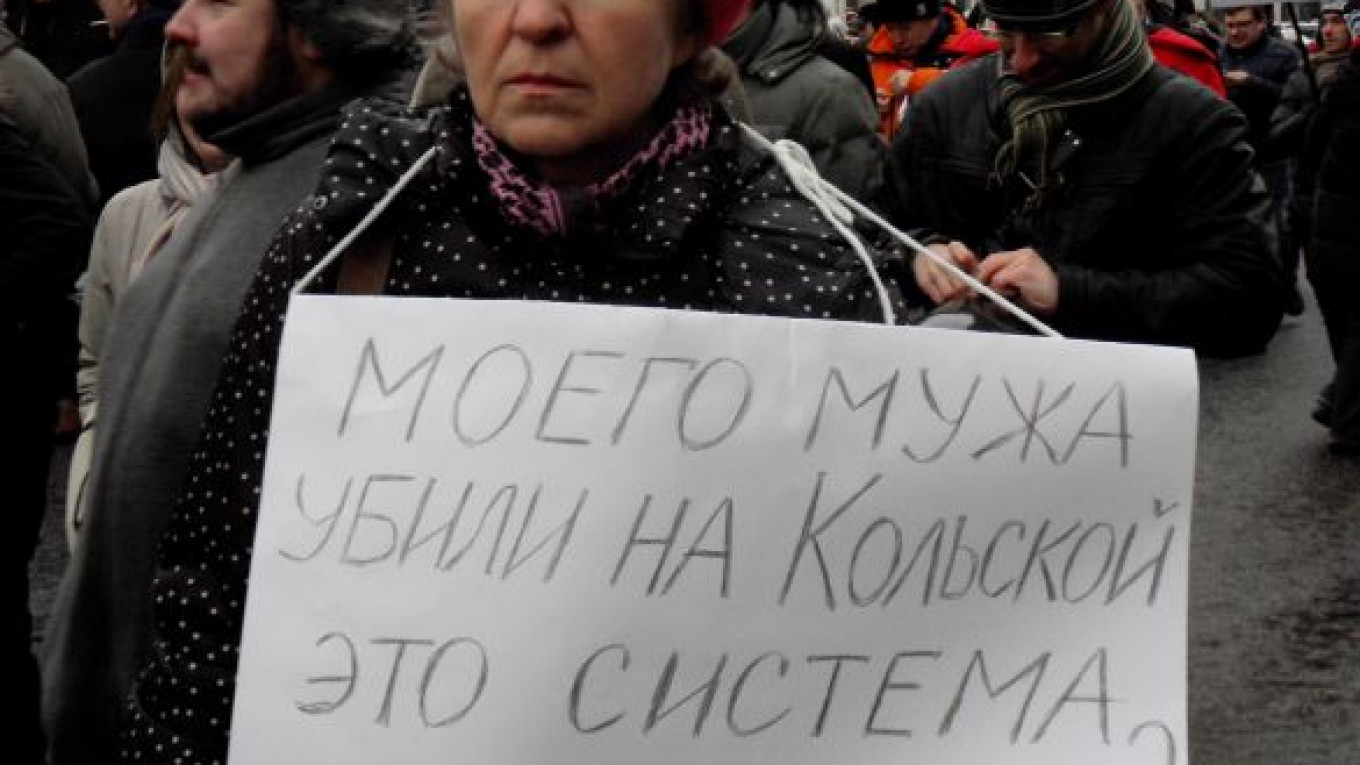

As the anti-election fraud protest at Prospekt Akademika Sakharova raged around her, Yelena Bogush seemed out of place.

While most of the democracy-hungry crowd held up signs demanding "Fair elections," or the ouster of "The party of crooks and thieves," Bogush clutched a sign close to her chest, reading: "My husband died on the Kolskaya platform. The system killed him. Who is next?"

Six days earlier on Dec. 18, her husband, Ilya Kartashov, was one of 53 people who disappeared when the Kolskaya offshore oil-drilling platform sank in the frozen waters of the Sea of Okhotsk some 11,000 kilometers from Moscow.

News of the shocking tragedy has been largely overshadowed by the political turmoil shaking the country since the disputed Dec. 4 State Duma elections sent tens of thousands of protesters into the streets.

But Bogush — a petite blonde with sharp eyes — is determined to keep pressure on the state-run companies involved and to make sure that people hear her belief that the government is guilty of "annihilating its own people."

"I am nearly certain that it is the management of the companies that is responsible. People on the platform were caught in a trap. At each stage the only thought was, 'How can more money be saved?' For the safety of the people there was never enough money," she said.

It was a brutal winter storm that caused the Kolskaya to sink beneath the waves as it was being towed to Vietnam after a three-month stint out to sea in the Far East.

But the story of the doomed oil rig begins in April 2011, when Gazprom subsidiary Gazflot commissioned state-run, Murmansk-based drilling company Arktikmorneftegazrazvedka, or AMNGR, to drill for oil on a shelf 200 kilometers off the coast of Sakhalin.

The AMNGR platform, the Gazprom Kolskaya, arrived in Magadan in August and was towed into position the following month. Built in 1985 by Finnish company Rauma-Repola, the Kolskaya had already passed the average lifetime of a floating oil rig of about 18 years, experts say.

The aging Kolskaya was plagued with problems before it even arrived, according to documents provided to The Moscow Times by Natalya Dmitriyeva, daughter of towing operation Captain Mikhail Tersin. He had kept the documents in his personal files, and they have since been handed over to prosecutors.

Dmitriyeva says when her father — a 30-year veteran — was given the assignment to move the Kolskaya, he told her the job was "simply impossible."

"He was nervous and angry," Dmitriyeva said.

The earliest document dates back to May 2011, when an insurance company informed AMNGR deputy CEO Vasily Vasetsky that the platform had several cracks in the area of its nose that needed repair.

"Given the successful preliminary repair the platform can be transported on Aug. 31," an inspection certificate issued by the Russian Maritime Register of Shipping stated on Aug. 25. The same document also demanded that a permanent repair be made within a year.

Dmitriyeva says she thinks that during the storm, the cracks opened and caused the platform to sink. Her father did not survive.

"My father worked for this company for years, and they always saved money at the cost of people's safety," she said.

In the spirit of her father who, according to Dmitriyeva, was "very truthful and always fair," she says she wants to make all the information she has public in the hope that those responsible will be punished.

"Father loved his job, he loved the sea. He always wanted his ashes to be spread over the sea," she said tenderly.

Even more telling is a document from the platform's manufacturer that explicitly stated that "towing is prohibited in the winter, in winter seasonal zones."

But on Dec. 11, a towing ship, the Neftegaz 55, joined by an icebreaker, the Magadan, arrived to move the platform and its 67 crew members. A week later, the platform sank. Ultimately, 14 people were saved and 17 bodies later found and identified, but 35 remain missing.

Investigators with the far eastern transportation branch of the Prosecutor General's Office have opened a criminal case after determining that "violations in the towing of the platform" were the main reason for the accident. They say the platform should not have been towed in the winter and there were too many people on it, according to a statement on their website.

Horror on the High Seas

Survivor Alexander Kovalenko, who was in charge of the drilling rig, said he had argued that no one should have been on the platform as it was being towed.

"Everybody knows that people should not be left on the platform," Kovalenko Komsomolskaya Pravda.

He says only Gazflot workers were removed despite his request that the AMNGR crew be moved onto the icebreaker Magadan before the operation started.

"We would have to pay for the icebreaker — rent and fuel. So don't ask that question again," he says the main engineer of AMNGR, Leonid Bordzilovsky, told him by phone from Murmansk.

Kovalenko said Tersin advised management in Murmansk to take a safer route along the Kuril Islands to hide from the storm, but was instructed to follow the sea because it was shorter.

When the storm began getting severe on Dec. 16, the platform started to move faster and began shaking, survivors said. On Dec. 17, part of the Magadan's tow rope broke. AMNGR Murmansk was informed and asked to send another ship, Kovalenko said, but he told Komsomolskaya Pravda that the request was ignored.

On the night of Dec. 18, the nose of the Kolskaya platform started to go under water. Water flooded through the portholes and into the galley, knocking out walls between the cabins.

In the morning, Kovalenko said he was yelling on the phone with AMNGR in Murmansk: "We will drown with the platform and will all die!"

At 9:24 a.m. that morning, the SOS signal was given. The platform crew was reassured that helicopters were on the way.

But rescue pilot Vasily Khristoradov told the far eastern news site

Sakhalin.info that the first choppers were not dispatched for nearly 4 1/2 hours following a squabble over who would pay for the operation.

According to survivors, those who waited on the platform for helicopters all died, like Andrei Dmitriyev.

"His friend who survived told me that my brother was waiting for the helicopters to come, whereas he himself decided to jump," Dmitriyev's sister Natalya Pankratova said.

Her brother was only a 25-year-old drilling assistant, who had just started his job. He had no experience coping with such a deadly situation.

"As soon as he started working for AMNGR, he started complaining about how horrible and careless the attitude toward the employees was," she said.

In no time, the Kolskaya slipped into the water. Some, like Kovalenko and survivor Sergei Grauman, an assistant driller, jumped off early enough to be saved.

"Then the real horror started," Grauman told Komsomolskaya Pravda. "The Magadan was not saving, but killing people."

Both he and Kovalenko said the giant ice-breaking ship was ill equipped for a rescue operation and that neither of them had the strength to climb up the net that was lowered by its crew. They were ultimately saved by the crew of the Neftegaz.

Chillingly, they watched as their fellow crewmen floundered in the water and then got sucked under the nose of the Magadan.

Survivors, relatives and maritime experts believe that the crew could have been saved during many different stages of the towing operation.

"Why were people left on board during towing? Why did they not save anyone when problems occurred?" asked Dmitry Svistunov, the son of Nikolai Svistunov, the rig's doctor who remains missing.

Maritime expert Mikhail Voitenko told The Moscow Times that he thinks an honest investigation into the disaster would reveal a great number of errors. He also suspects that the platform suffered from greater technical problems than have already been revealed, as the "very experienced" owners of the Magadan would not have agreed to a potentially dangerous operation otherwise.

Voitenko says anyone with experience in seafaring would expect a storm of that kind during that time of the year in the Sea of Okhotsk.

"I think someone really wants to prohibit an objective investigation into what led to the death of the Kolskaya platform," he said.

An Unpredictable Tragedy

The companies involved deny they are to blame for the accident. In an interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda, AMNGR's acting general director Yury Melekhov said it was not too late in the year for towing. He said the platform was designed to carry up to 100 people and that it was Captain Tersin who gave the order for people to stay onboard.

In a news conference on Dec.19, he acknowledged that there were three cracks in the platform, but insisted that "they were already fixed in Magadan. The repair took 20 days and was finished Aug. 31."

The icebreaker Magadan and ship Neftegaz were "fully prepared for the operation," he insisted.

"The evacuation of the platform was carried out in an organized manner. All the men were dressed in hydro costumes," or dry suits designed for extreme temperatures, he added.

The Moscow Times first contacted AMNGR on Jan. 20 with a list of questions about the incident. After failing to respond for 10 days, a spokesman for the company promised on both Jan. 30 and Jan. 31 that answers would come "tomorrow." He finally assured The Moscow Times that a response would be sent by mail, but it had not been received by press time.

Voitenko says by law the main responsibility lies with AMNGR, but Gazprom is not off the hook as they requested drilling in December, knowing that the platform needed to be transported back.

Long before the accident, local environmental activists filed a suit against Gazprom. Their main concern was that the rig was located in an area that is home to a very rare species of fish. In October the environmentalists appealed to President Dmitry Medvedev with their concerns. Neither the company, nor the president responded.

"A company that allows itself a violation of this sort can be expected to violate all sorts of other laws," Alexei Knishchnikov, of the World Wildlife Fund Russia, told The Moscow Times.

The active search for survivors ended on Dec. 22. Experts say that even in a hydro costume, a person can survive no longer than 10 hours in such conditions.

Many relatives are still waiting for the return of their loved ones.

"Everyone is broken or still in hope," Bogush said.

Dmitry Svistunov says he still waits for his father, Nikolai, to come back.

Svistunov was given hope after his mother received an SMS from his father's phone on Dec. 22 and Dec. 23, cryptically reading, "*728#." The same SMS was received by another relative. More than a month later an empty lifeboat from the Kolskaya was found washed up on the steep and rocky coast of a remote island in the Kuril chain, but there was no sign of survivors, RIA-Novosti reported.

Svistunov has asked several agencies for help in trying to locate the phone, but with no success, he said.

"He was a very good-hearted and soft person. Nevertheless, everyone respected him, which is rare. Usually good-hearted people are not very well respected," Svistunov said. "You cannot possibly imagine how much I loved him."

His father worked on ships all his life and had already retired, but he needed money and decided to take the Kolskaya job, Svistunov said.

Bogush said she received the last call from her husband on Dec. 11.

"He was so happy that they were done and would leave finally, he also told me that he would not have a signal before arrival," Bogush said.

For her, missing means dead. A survivor told her that he had jumped off the platform with her husband — therefore she believes that he was swept under the Magadan.

Bogush, who is originally from the Chechen capital of Grozny, is left with a 7-year-old daughter and has no close relatives in Moscow.

Her daughter Valya "grew up suddenly," her mother said. She thinks that Valya understands what is happening.

"I think she was used to him being there and then not being there. But now she asks me, 'Will you get married again?' 'No,' I say," Bogush said.

Seeking Justice

As she describes the man she married, Bogush speaks in a steady, convincing voice. A nervous movement of her left hand and the occasional twitching of her face reveal what she is going through. Still, she refuses to accept her grief.

"The other relatives all pity one another — that is the wrong approach. I want those responsible for the accident to be found and punished," she said.

Her husband, Ilya Kartashov, was a veteran oil platform worker. In fact, he had worked on the Kolskaya between 1985 and 1990. He left AMNGR in 1998, but was asked to come back in 2010.

A senior mechanic, he learned his skills on the job. Born in Baku, Azerbaijan, he started working on oil rigs in the Caspian Sea as a teenager. He later graduated from a Baku technical college.

The couple met on an oil rig in Mexico in 1998, where Bogush worked as a translator.

"He loved his job. He was always working more than was expected of him. He did the same at home, always checking technical devices. 'Does the TV and the radio and this and that work?' he would ask when he called," she said.

His colleagues described him as calm and levelheaded — never raising his voice and always offering support and understanding.

Kartashov's desire for hands-on work meant he was not cut out for a desk job.

"I would rather go right to the source and do practical work," his wife quoted him as saying.

Bogush, Svistunov, Pankratova and Dmitriyeva were informed that their loved ones were insured by the company for $30,000.

"When I read that the insurance was $30,000 — that the life of my husband costs that little — I was amazed." Bogush said.

Tersin's daughter Dmitriyeva wants to believe that those responsible will be prosecuted.

"I want to believe that the country I live in cares about its people," she said.

Several top Gazprom executives, including the deputy chairman of the board, Alexander Ananenkov, retired early, Gazprom's press service announced on Dec. 30.

Although his retirement does not appear connected to the Kolskaya tragedy, Bogush feels a certain satisfaction from it, she said.

The relatives of the victims are organizing a lawsuit against AMNGR. They also sent a letter to Medvedev asking for the creation of a government commission to investigate the accident.

"I can't describe everything that I felt and saw in words. It was the worst day in my life. I still cannot believe what happened, but I do know: These people did not die, they were killed!" an 18-year-old boy whose brother died on the Kolskaya and requested anonymity wrote to The Moscow Times.

"The country seems to have forgotten about the tragedy entirely," another relative who requested anonymity said.

Many relatives share the sentiment.

"I just can't believe that my husband died so that some oil managers can buy themselves another car," Bogush said, finally in tears.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.