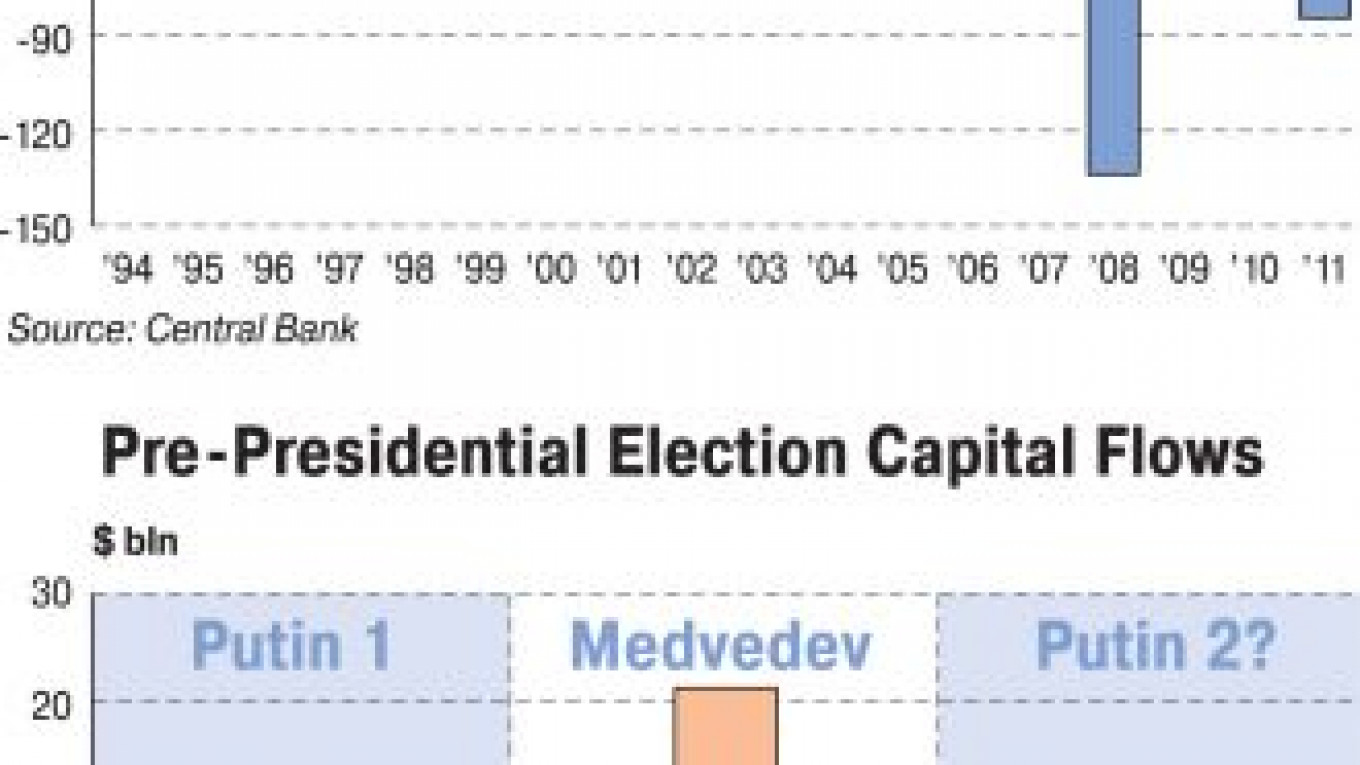

Capital outflows totaled $84.2 billion last year according to data released by the Central Bank on Wednesday, the second-highest figure since 1994 and a big jump from the $33.6 billion that exited Russia in 2010.

The cash exodus crescendoed to $37.4 billion in the final three months of 2011 against a background of mass street protests in Moscow and financial crisis in Europe.

Politicians and central bankers were repeatedly forced to revise their predictions about capital outflow over the course of the year as they were left behind by rising figures. About $19 billion was logged in the third quarter and $7.3 billion in the second quarter.

In what now appears to be a foolish hope, Central Bank Chairman Sergei Ignatyev said in April that inflows were possible during the last eight months of the year. “You can’t have such strong capital outflow for so long,” he said.

The final count of $84.2 billion was higher than the Central Bank’s November estimate of $70 billion and $4.2 billion more than Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s forecast as late as Dec. 26.

Experts contacted by The Moscow Times said the European debt storm and other macroeconomic factors outside of the Kremlin’s control played a significant role in sucking money away from Moscow. But most added that disputed Duma elections on Dec. 4 and huge opposition demonstrations had fueled the trend.

While the Central Bank did not publish monthly data for the fourth quarter, Deputy Chairman Aleksei Ulyukayev said in December that capital outflow was $14.7 billion in October and $10 billion in November. Capital outflow in December was, therefore, about $10.2 billion.

Ivan Tchakarov, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, said in a research note that the acceleration in the last quarter was “at least partly related to the heightened political uncertainty in the aftermath of the Dec. 4 parliamentary elections.”

Aton head equity strategist Peter Westin told The Moscow Times that the above-average figure for December meant “the political factor has been important.”

Yet he added that it was impossible to attribute the $24.7 billion outflow in October and November entirely to election jitters. Pointing to the spike in European bond yields and debt repayments during that period, he said the primary cause was likely to have been European parent banks drawing funds away from their Russian affiliates. “A big chunk of the money that was flowing out came from European banks in Russia,” he said.

Deputy Economic Development Minister Andrei Klepach criticized foreign lenders like UniCredit and Societe Generale in October for pulling liquidity from their Russian units.

The chief economist at Otkritie Capital, Vladimir Tikhomirov, said another reason for the high fourth-quarter outflows was the resources Russian companies and banks had been forced to divert to refinancing their obligations on European debt markets.

But he added that a general mood of political uncertainty linked to parliamentary and presidential elections was undeniably weighing on domestic and foreign investors. “When you stay on the sidelines you have to keep your cash in a safe place — which is obviously somewhere outside the country,” he said.

The Central Bank monitors all cross-border financial transfers to produce the net capital flow statistics. Russia has only recorded an annual inflow twice since 1994 — in 2006 and 2007.

The highest-recorded negative was $133.7 billion amid the throes of the 2008 global economic crisis. The size of recent outflows are relative, however, as Russia’s gross domestic product has grown steadily during the 2000s.

While improvements to the investment climate — including a reduction of corruption and a strengthening of the rule of law — would help slow the exit of cash, the Kremlin has only limited options because international macroeconomic factors are so important.

Russia abolished capital movement restrictions in 2006, and Putin said last month that the measures would not be reinstated even if the financial flight continues to escalate.

“The flow of money into and out of the country is a barometer,” said Yevgeny Gavrilenkov, chief economist at Troika Dialog.

“If we are talking about some sort of short-term action, then it’s unnecessary and pointless,” he added. “You will start to break the barometer.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.