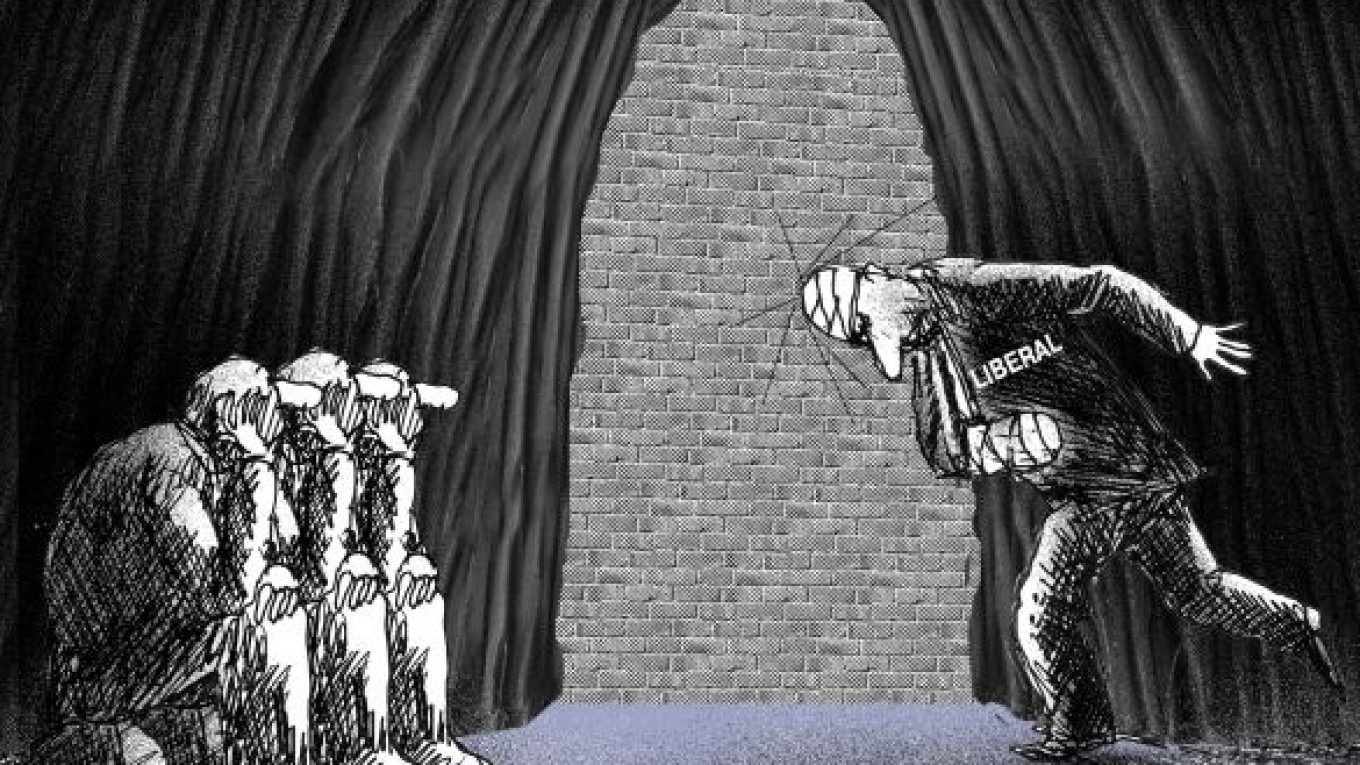

The liberal opposition is often called upon to repent for the “sins” of the 1990s, a period strongly associated in the public mind with liberal reforms.

We are told that as soon as liberals and democrats repent for our mistakes, the public will believe us, vote for us and offer us various forms of support.

We are told that only our repentance will convince people that if the liberal opposition ever gets voted into the Kremlin, it will not simply replace one corrupt and ineffective power vertical for another.

At the same time, it is unfair to say the entire 1990s was a dismal failure. The decade’s reforms contributed a great deal to Russia’s development, including a free-market economy, freedom of the press and other democratic liberties.

But Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, thanks to his powerful propaganda machine, has convinced millions of Russians that liberal ideas and the liberal political movement are to blame for all the country’s current misfortunes. This is a cynical attempt to deflect attention away from the corruption, stagnation and erosion of democracy that have occurred over the past 11 years under Putin’s rule.

That being said, it is only fair to acknowledge that there were many mistakes made by the architects of liberal economic and political programs in the 1990s. It is important to learn from these mistakes, particularly if the liberal opposition is trying to position itself as a viable political and economic alternative to autocracy.

The main problem with Russia’s liberalism of the 1990s is that it was all too often half-hearted and misguided at best and distorted and corrupt at worst. The four main problems of the decade’s liberalism were:

1. Many influential reformers of the 1990s were not real democrats. What’s more, they were afraid of democracy and even the idea that political forces with differing values could come to power through free democratic elections. This explains why many liberals of the period praised Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and believed that his model of development — modernizing through authoritarianism — would be particularly appropriate for Russia.

2. Far too many liberals in the 1990s neglected the importance of building effective democratic institutions. The very ideas of a strong parliamentary system, public control of government, federalism and an independent court system struck liberals of that period as harmful and absurd. They openly emphasized the need for strong presidential power and the bureaucratic vertical.

3. Liberal thinking was dominated at the time by an almost neoconservative belief that generous social programs and labor protection were irrelevant or even harmful. That is why it should come as no surprise that millions of Russians continue to hate liberals who oppose building a social welfare state.

4. Finally, many of the highly placed liberal politicians were unable to resist the temptations of enriching themselves through corruption — above all, through inside deals with their favorite oligarchs and bankers and opaque privatization schemes. What’s worse, some of those same liberals now occupy senior government posts in Putin’s regime, further discrediting the word liberalism in Russians’ minds.

For the new Russian liberalism to succeed politically and to thereby help the country prosper, it will have to adopt programs to build strong guarantees of political and economic freedoms, increase competition and create a favorable business environment. It also will need to declare a new program to build up the state and to develop the country’s human capital.

The new liberals need to focus on building an effective democratic state and public institutions, including independent regional and municipal governments. Above all, to build faith and trust in the country’s government, liberals must be an example of honesty and decency. To be sure, the temptation to embezzle funds is large in any government position, but liberals must prove to Russians that they have strong morals and can place the public good over personal gain. The battle against corruption must start from the top, and the country’s top leaders must adopt a zero-tolerance policy.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition Party of People’s Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.