Roman Talalin prefers to sip his tea with a Snickers bar.

The 21-year-old and his ex-girlfriend got acquainted during their daily tea drinking sessions in Volgograd. Talalin liked the ritual so much that he decided to create a social networking group in honor of Snickers, the chocolate bar that the couple always ate with their tea.

The group now has more than 14,000 members who share Talalin’s hunger for foreign chocolate.

Soviet-era brands of chocolate remain the key players on the market, but the aging consumer base is starting to lose its nostalgic pull to the Soviet names. Foreign producers are also attracting a bigger following by introducing Russians to new tastes.

A large patenting wave swept the Russian chocolate market 12 years ago, said Natalya Serbkova, who handles patent issues at the Slavyanka confectionary factory in Stary Oskol, Belgorod region. This wave has left Russian confectioners scrambling for the right to give their candy Soviet names. For them, these names still translate into quality and customer loyalty.

“Those who were born before 1990 know the names perfectly,” Slavyanka chairman Sergei Gusev said. “They are still nostalgic for them. Many have grown up on them and love them.”

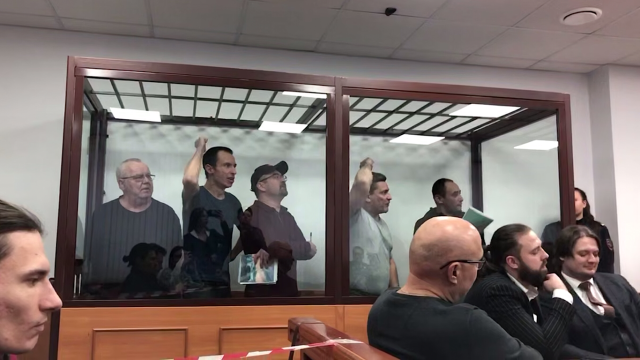

The fight over Soviet branding has intensified in the past four years. Moscow-based United Confectioners, which owns Soviet chocolate kings like the Krasny Oktyabr and Babayevsky factories and holds the rights to 80 percent of all Soviet-era brands, has filed multiple lawsuits over regional producers’ use of similar candy names and packaging.

Slavyanka, for one, patented the Alina chocolate bar, but United Confectioners claimed that the wrapping, which features a young girl, is copied from its Soviet-named Alyonka. The conglomerate recently sued Slavyanka for 313 million rubles, although Gusev said earnings for Alina had only amounted to 4.5 million rubles since it was patented in 2003.

Kirill Kolodnitsky, director of the legal department at the Omsk-based Sladunitsa confectionary factory, suggested nationalizing the Soviet names of chocolate. His company is dealing with a 215 million ruble lawsuit that United Confectioners filed over the use of Soviet-name variations for two of its products.

Foreign producers are standing aside in the fight, instead preferring to put their money into innovations.

The strategy appears to be working since the companies without any Soviet brands of chocolate in their portfolios are increasing their share of the Russian market. After United Confectioners, Mars, Nestle and Kraft Foods were the leading confectioners in Russia in 2010.

Swiss-based Nestle, which owns several facilities in Russia, has put out three new variations of the Rossiya–Shedraya Dusha (Russia - Generous Soul) chocolate bar this year and continues to reinvent its packaging. The packaging for its premium chocolate Komilfo won a marketing prize in 2007.

"The Russian market is developing," Nestle said in an e-mailed statement. "The producers that can offer the customer the best quality for a rational price will be most successful."

Alpen Gold, made by U.S.-owned Kraft Foods, is now the leading chocolate bar in Russia. Last year, the company introduced a variation on the bar, a new line of chocolate under the Milka label and the first porous chocolate bar with a berry filling.

The company plans to introduce more new products in the near future.

"Russian consumers are hungry for new ideas, new tastes and experiences, and underlying this they appreciate and expect improved quality, so to take and hold leadership one should invest in innovation," Kraft Foods said in an e-mailed statement.

Russian confectioners have also begun to turn away from their reliance on Soviet brands and put more attention on new products. Slavyanka, which now refuses to produce candy with Soviet names, has developed 150 new chocolate brands over the past 10 years.

"As the population passes away, the Soviet names will be forgotten," Gusev said. "They are already largely forgotten."

Getting the new products on the market is a risky move. Gusev said it takes at least three to five years for a new chocolate brand to develop a loyal following.

The prospects, however, are also tempting. Chocolate consumption per capita in Russia is 50 percent less than in Western European nations. The average Russian consumes four to five kilograms of chocolate products per year, while the Irish and Swiss eat more than 10 kilograms per year, according to Nestle's statistics.

The consumption per capita in Russia is expected to jump to 11.8 kilograms per capita by 2015, according to a BusinesStat study released last month.

This could mean that more people will be joining Talalin's group as they munch on Snickers with their tea.

"Chocolate is happiness that you can taste," Talalin said. "It's the analogue of unconditional love."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.