As each new round of Russia’s seemingly endless series of military reforms gets under way, the military always laments over the destruction of its great army. The script is well known: The top brass issue dire warnings about how cuts in the military budget and personnel will undermine the country’s national security. Now the military faces a new blow: reforms to the armed forces’ educational system.

The biggest news is that military academies will not be accepting new students this year and next. What’s more, in 2009 about 25 percent of graduates from those schools were offered posts as sergeants, not officers. This year, that number might reach 50 percent of the 15,000 graduates. The only other option for those rejecting the rank of sergeant is to leave the military.

By taking on military education, reformers are attacking one of the most important modernization issues facing the armed forces. The largest reforms that have been executed so far — eliminating skeleton units and firing more than half of the officer corps — will be pointless without making drastic changes to military education.

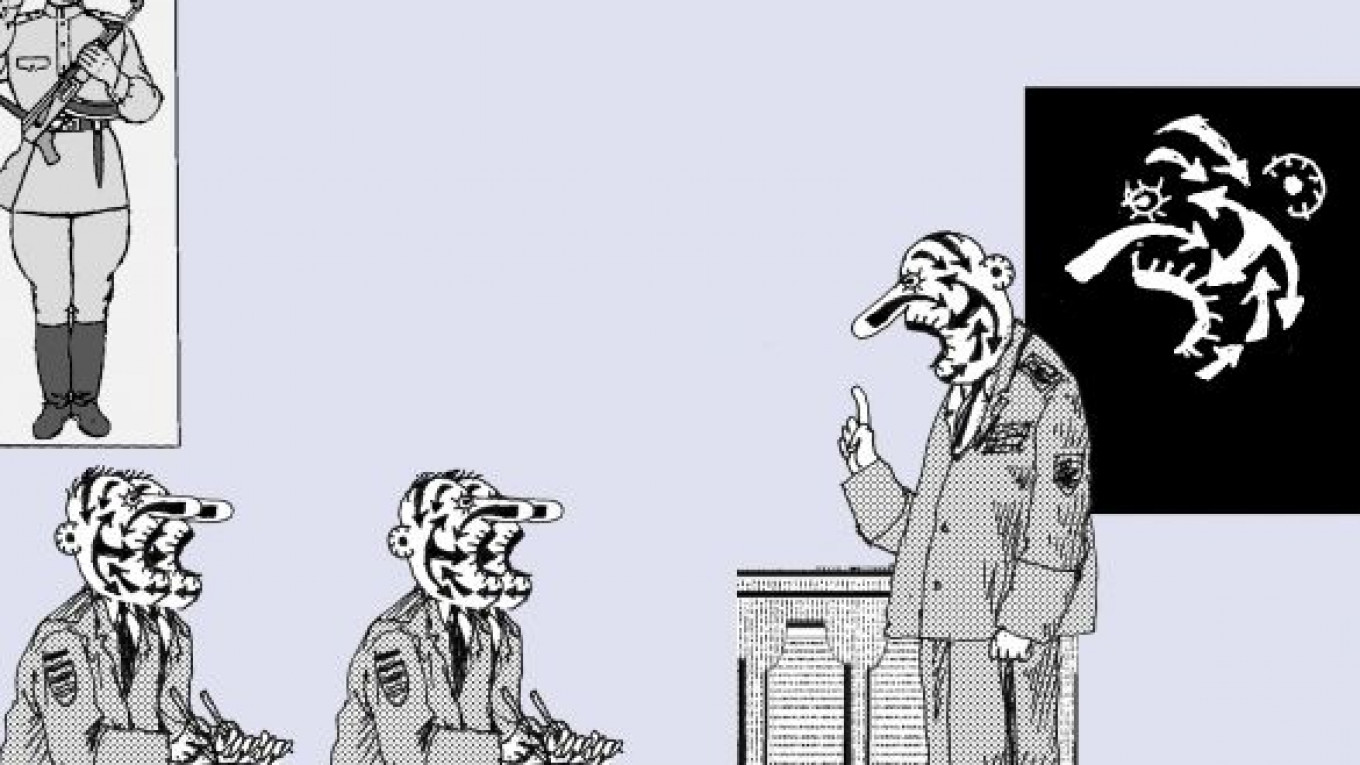

Why did military academies place a moratorium on accepting new students for the next two years? The main reason is that reformers have rejected the mass-mobilization army concept. According to that model, millions of reservists are called to duty when the country is in danger. And when troops are deployed in huge numbers, officers — especially junior officers — become cannon fodder, and whatever knowledge they have is of no use to anyone.

But the two-year halt to admissions cannot be explained exclusively by the fewer officer posts resulting from cuts to the number of military units and divisions. Today, the reformers have finally realized that Russia’s military academies have not been training professionals but low-skilled technicians who are only needed in a mass-conscription army. The educational process in most academies is still designed to give the future officer only as much knowledge as is necessary to master one or two specific types of equipment.

I remember how generals reacted with both surprise and disdain when they were introduced to the programs of the three U.S. military academies. It turns out that Army officers at West Point, Naval officers at Annapolis and Air Force officers at Colorado Springs are not trained to specialize in specific military equipment. Instead, their programs are split almost evenly between the natural sciences and the humanities. Students are taught mathematics, physics and chemistry. That approach makes it easy for their graduates to go on to master everything from aircraft technology to a ship’s navigation equipment. In addition, the graduates of U.S. military academies and universities not only become experts in their field of specialization, they also receive a broad education in the humanities, which gives officers an understanding of their place in the complex modern world.

One of the reformists’ goals is to make the military education system stricter, like in the United States. Under Russia’s old education system, students who receive a “D” on tests were allowed to retake the exams. But under the new system, students who receive bad grades can be expelled.

The two-year admissions hiatus is necessary to mobilize resources and tackle the Herculean task of fundamentally restructuring the educational program.

But it is not clear how all of the military education reforms will be implemented and who will teach the teachers. Twenty years ago, it was simple enough to rename the Marxism-Leninism departments at military academies as political science departments, without instructors having to change much in terms of their academic programs and methodologies. Nonetheless, reform optimists are confident that by dedicating more time to teaching foreign languages to young officers, they will have a greater opportunity to pursue their own self-improvement outside the classroom.

Either way, the Defense Ministry is determined to build a system in which military academies try to convince students to treat the military as a profession and not just as a tool to master a narrow set of skills. They want students who are sincerely motivated to learn and increase their broader qualifications.

But military education reforms will be useless if fundamental changes are not made to the system by which officers can advance in rank. All these calls to intellectual development appear hypocritical considering the fact that the career of every Russian officer is still completely dependent on the whims of his immediate superior officer. Even if an officer is a military genius, he will never advance if his superiors are opposed for any reason. To change that situation, it is necessary to grant higher ranks based on a system of open and transparent competition. Unfortunately, this very important item has not yet made its way onto the reform agenda.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.