Kiev, or Kyiv, as the Ukrainians say, is a gorgeous panorama of golden-domed churches. If you go to the Kyiv-Pechersk Cave Monastery and then take in the adjacent World War II memorial complex with its giant silver statue of the grieving Mother, you can see Ukrainian history from the 11th to the 20th century in a single sweep. As for the night life, well, this autumn there was no need to go in search of clubs, as the main thoroughfare, the Khreshchatik, was one continuous orange street party.

But what to do with that extra free day? Despite the distractions of contemporary Kiev, I couldn't get Chernobyl out of my mind after coming across a web site written by Yelena, a biker who zooms down the abandoned roads of the contaminated Zone and calls herself the Kid of Speed. On her web site, kiddofspeed.com, Yelena waxes lyrical about the peace of the countryside, left to nature since the residents were evacuated following the nuclear power plant disaster on April 26, 1986.

But Yelena detests journalists and refuses to give interviews. I was stuck until I found a small business run by a former Chernobyl worker that organizes single- or multiple-day tours to the Zone. Chernobyl External Services deals mainly with foreign specialists going to ecological conferences, of course, but it will also get out the white minibus and roll out the red carpet for the curious layperson. If 20 people can be found to fill the bus, then the cost for each individual is only $60.

The firm says that on a short visit to Chernobyl, the danger from radiation is now no greater than flying in an airplane, and advertises its guided tour as a "safe adventure." In fact, CES is not the only company offering trips to the Zone, although the number of takers among visitors from overseas has evidently not been great so far. The contaminated air is only one disincentive: In order to enter the 30-kilometer exclusion zone that was thrown around the nuclear plant after the accident and is still in force, visitors also need permission from the SBU, the Ukrainian successor to the Soviet KGB.

Tour leader Sergei Akulinin works with good humor and military precision. "See you at the bus in eight-and-a-half minutes," he joked. Not eight, not nine, but eight-and-a-half.

On the eve of the tour just over two weeks ago, I left Kiev for Slavutich, the new town that was built for atomic workers after the accident made their old town of Pripyat uninhabitable. It is a journey of 186 kilometers to the north. Slavutich, with a population of 25,000 people, is like a model of the old Soviet Union, as different Soviet republics helped to build it.

Dinner was in a converted bomb shelter, now a restaurant with nautical themes called Nautilus. The wall decorations hinted at the Great Barrier Reef. Trout was on the menu, not locally caught. The drinking water was bottled. Accommodation was in the three-star European Hotel, originally built by Finns to be the town hospital. The tour started at 7 a.m. sharp.

Before the tour began, Sergei took me to the Slavutich Cultural Center to see its explanatory exhibition and memorial bells. The diagrams of pipes and turbines could only be of interest to a specialist, but I was moved by the sight of 30 faces staring from photographs. These were the first victims who died from massive doses of radiation straight after the accident, which happened because an experiment on the fourth bloc went wrong. On another wall was the face of Viktor Bryukhanov, the then-director of Chernobyl, who was made to bear the responsibility and jailed for 10 years.

"It was not an atomic explosion but a heat explosion," Sergei made clear. Nevertheless, radioactive dust from the ruined reactor was carried on the wind over a wide area of Ukraine and into neighboring Belarus and Russia. The communist authorities failed to warn the population immediately -- indeed, May Day parades went ahead in Kiev -- and it was Sweden that first alerted the world to the disaster.

AP Workers who covered the ruined fourth reactor pose in 1986 with a poster that reads, "We Will Fulfill the Government's order!" Many later died of radiation poisoning. | |

Under pressure from Europe, Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma closed the whole power station in 2001. Which was why I was astonished to start the tour the next morning by commuting to the mothballed power station on an electric train together with hundreds of workers from Slavutich. Far from being a ghostly scene, the power station is a hive of activity, as the workers have to maintain the metal sarcophagus that seals the fourth reactor and keep an eye on the other closed blocs.

The route to Chernobyl from Slavutich runs through the territory of Alexander Lukashenko's Belarus. Because I did not have a visa to enter the country, I went on the train with all the sleepy workers, who are not checked by the border guards. The driver of the white minibus took my luggage over the Belarussian border and met me with it at the station, which is back inside Ukrainian territory. I had spent 10 days in Kiev with the orange protesters, and if Lukashenko was interested, my rucksack contained nothing but dirty clothes.

The train passed through a landscape of pine forests and rust-colored marshes. Storks' nests and bunches of mistletoe decorated the dark skeletons of the deciduous trees.

The workers poured out onto a platform enclosed with corrugated iron and trudged down a plastic-floored corridor to machines that checked them for radiation. Then they changed into the clothes they keep for work -- turquoise jackets with black suits underneath -- so as not to spread the contamination back home. They are happy to work here because the wages at Chernobyl average $350 per month, which is good pay by Ukrainian standards.

After the dosimeter machine pronounced me clean, I was whisked off to the Sarcophagus Viewing Center, where you get to watch a video and see a scale-model of the inside of the wrecked fourth reactor while looking out the wide glass window at the encased reactor itself. For some reason, I had expected a dome, but the sarcophagus, built to last for 30 years, looks more like a roof, gray as a crow's wing.

In elegant English, tour guide Yulia Marusich explained that the sarcophagus is unstable and that plans are being drawn up to replace it, as the plutonium and other elements in the reactor will be lethal for centuries to come.

Next stop was the ghost town of Pripyat, abandoned in the days immediately after the accident. The silence was eerie. Sergei pointed to his old flat in an apartment building at 34 Lesya Ukrainka. He sighed. "My wife and I used to push our sons' baby carriage up this alley. Our youth is here." Stray dogs barked. We thought it wise to move on.

The air smelled sweet after the car fumes of Kiev. Blue jays flitted in the bushes. In the absence of people, the streets and countryside around were completely litter-free. The red rose hips and black wolfberries looked a normal size. Sergei said that after the accident, monster pinecones had appeared and the needles of the pine trees had grown the wrong way around, but that gradually Nature had righted herself.

We drove on to the town of Chernobyl, an old settlement with little cottages and a white, blue and yellow Orthodox church. Here, specialists from the Ukrainian Emergency Situations Ministry work 15 days on and 15 days off, studying and cleaning up the Zone. We lunched royally in their cafeteria; from the taste of the food, there was nothing wrong with it.

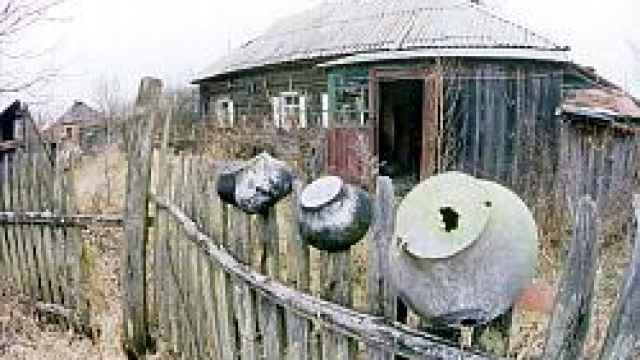

Itar-Tass The silence is eerie in ghost towns like Terekhi, abandoned after the accident at Chernobyl. | |

"The tour operators include a day at Chernobyl," he said. "Twenty to 30 people sign up, but when Day Zero comes, most of them decide to stay in Kiev. We get one or two people coming. Mostly they have an interest in ecology."

Our last stop was the village of Ilyntsi, once home to 100 people but now nearly deserted except for a few elderly residents who returned after evacuating to other regions of Ukraine. Up a lane, some men were cutting wood. In the yard of one house, clean washing was hanging on a line. We rang the bell and were invited into the home of Galya Pavlovna.

Weeping, the old woman, originally from southern Ukraine, explained how she had married for a second time and come to the Zone with her new husband. Then he had died and she had been left in what she called an "alien" place with few social services.

As a parting gift, Pavlovna pressed on me a pillowcase decorated with Ukrainian embroidery. To my shame, I passed this gift from the heart, together with myself, through the dosimeter when I departed. The radiation reading was normal.

To book a trip to Chernobyl through Chernobyl External Services, contact Sergei Akulinin at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.