A quarter of a century ago — it sounds rather lofty, but it feels like yesterday, only in a completely different country, or maybe even another world.

I have a vivid memory of October 1992, the short peaceful interval between the barricades around Yeltsin’s White House office in 1991 and the tanks shelling the very same building in 1993.

The Moscow Times office was just around the corner, at the Radisson Slavyanskaya Hotel (we called it Radisson-Chechen). Meg Bortin was the passionate editor-in-chief, and we — a small but noisy and over-enthusiastic Dutch-American-Russian-British crowd — worked on Issue Zero.

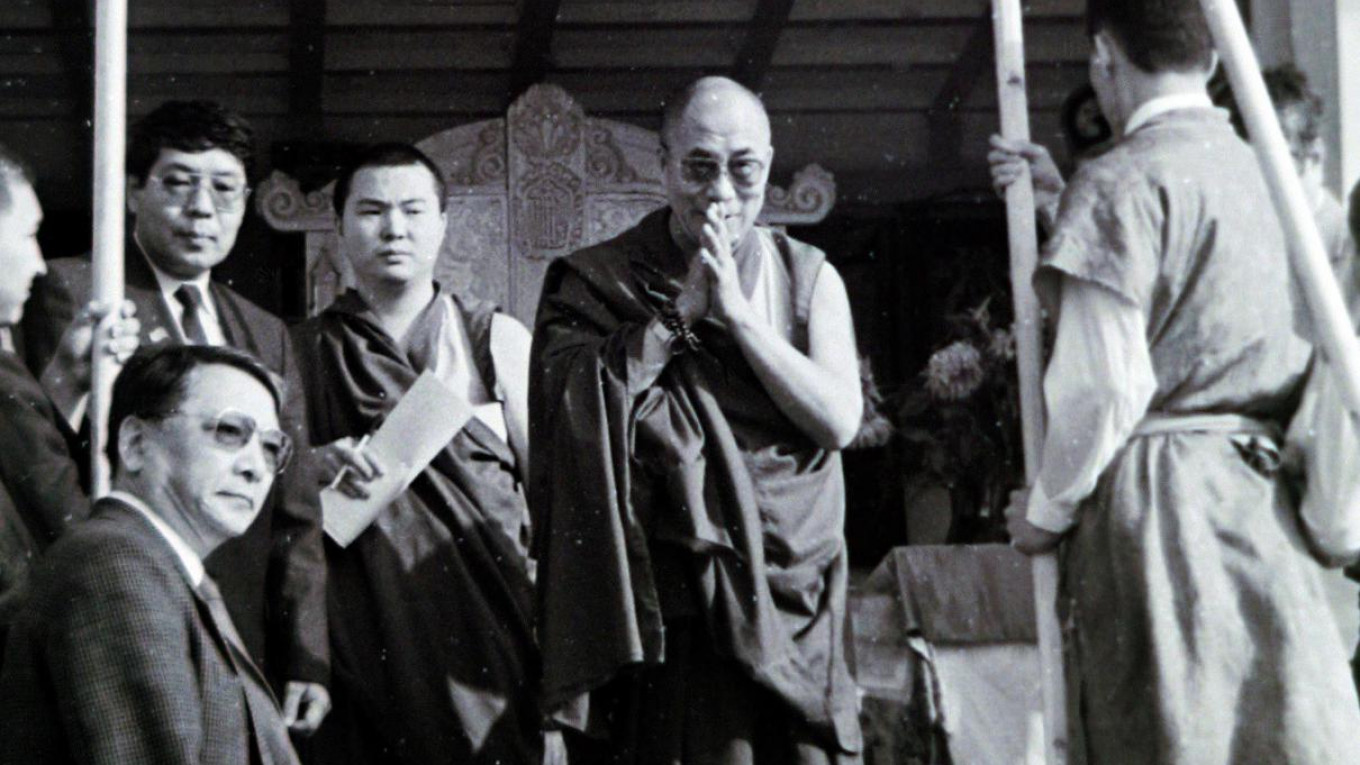

My city life column, entitled “Metro Diary,” got started with a piece called “Moscow Says: Hello Dalai!” about the privately sponsored visit of the Dalai Lama to the Russian capital. I remember boasting that at the end of a VIP tea party I was invited to, I secretly drank the tea left at the bottom of His Holiness’ cup. I have no idea why I did it, but it was fun.

Now, nothing — literally nothing, except for some of us human beings — is left from that era.

The White House now houses the Prime Minister, not Parliament, and is defended by a tall iron fence. The American co-owner of the Radisson Slavyanskaya, Paul Tatum, was shot in the back while walking down the stairs to the underpass by the hotel, and our office moved to Ulitsa Pravdy (Truth Street).

Ivan Kivelidi, the banker who organized and financed the Dalai Lama’s tour of Russia, was killed by a secret hi-tech substance in 1995, along with his secretary Zara who touched his poisoned phone. His Holiness Dalai Lama was last granted a Russian visa in 2004. I traded the metro for a car and driver, but kept the “Metro Diary” running for the whole decade.

The freewheeling ’90s stormed Russia like hurricane Boris, leaving behind the Chechen war, shock therapy, hundreds of thousands of dead bodies belonging to bandits, businessmen, homeless people and passers-by — and tens of thousands of millionaires.

If you want to see what a big, truly anarchic country is like, look no further than Yeltsin’s Russia. I called it “the land of unlimited impossibilities." People were free to do whatever they wanted, take chances and try their luck — but at their own peril.

In today’s Russia, when people try to scare you with the horrors of too much freedom, all they say about those years is crime, crime and more crime.

This is not exactly true. There was much less corruption than there is now because the role of the state was much smaller and social mobility was much more effective. Fewer journalists were killed and attacked because there was real freedom of speech. There was more courage and experimentation in arts and culture because there was absolutely no censorship. As for everyday life in the city — it was ugly, in bad taste, over the top, dynamic, dirty, violent, cosmopolitan — and never boring.

The decade’s last surprise, Mr. Putin, has turned the tide and revived some familiar old values, like patriotism, isolationism, militarism and the Orthodox faith. These values are overwhelming on television and in political statements, but they haven’t yet exerted total control over lifestyle and culture, like in Iran. Moscow today isn’t ideologically and aesthetically sterile or boring: there still are innovative events at galleries and theaters, rap battles and post-punk gigs at underground clubs, concept stores and hipster eateries.

If you’re twenty-something and you speak Russian and English, you can always find something worthwhile and entertaining. Of course, no one knows how long this will last.

In the meantime, I personally miss one thing in today’s Moscow — the atmosphere of adventure and optimism.

..........................................................................................................................................................................

Artemy Troitsky is a journalist and writer, now teaching in Tallinn, Estonia.

This article is part of The Moscow Times' 25th-anniversary special print edition. To view the entire issue click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.