It has been more than a decade, but Olga Rybkovskaya's voice still goes tense when she talks about her son's stint in hospital.

He was only ten years old when he was admitted to an intensive care unit in the Siberian city of Omsk, where the ICU had implemented a strict no-visitor policy. For eight days, his increasingly desperate parents waited outside closed doors, wondering what was going on with their child.

“He was fully conscious, and couldn't understand why his parents weren't there,” says Rybkovskaya. Though her son recovered, the experience scarred the family.

By law, close relatives of intensive care patients have visitation rights. In practice, however, hospitals frequently refuse access even in near-death situations, citing hygiene or other concerns.

For many Russians, such local injustices are part of daily life. Complaints tend to go ignored. “Making your voice heard is almost impossible and our politicians are completely out of reach,” says Rybkovskaya.

Meanwhile, taking your grievances to the streets can be risky. In Russia, attending an unsanctioned rally more than twice can land a person in jail. Faced with these prospects, most people simply put up their hands and say, Chto yest, to yest — it is what it is.

But technology might provide a way out of the conundrum. Earlier this year, Rybkovskaya launched a petition on Change.org, an online platform, demanding an open-door policy for close relatives of intensive care patients. Within weeks, it had gathered more than three hundred thousand signatures and snowballed into a subject of national debate in the media.

Hundreds of signatories shared their own personal tragedies. “We took my father to hospital with a haemorrhage,” one person wrote. “The doctors said: only fancy hospitals let you pay your way into IC. Here, you’re like everyone else. I waited outside on the stairs for five hours. Then a strange woman walks out and says: what’re you sitting here for? Your father has been dead for ages.”

The publicity eventually resulted in a written reminder from the Russian Health Ministry to hospitals to open their doors — “a victory,” in the words of the young and enthusiastic head of the Russian-language version of the Change.org website, Dmitry Savelau.

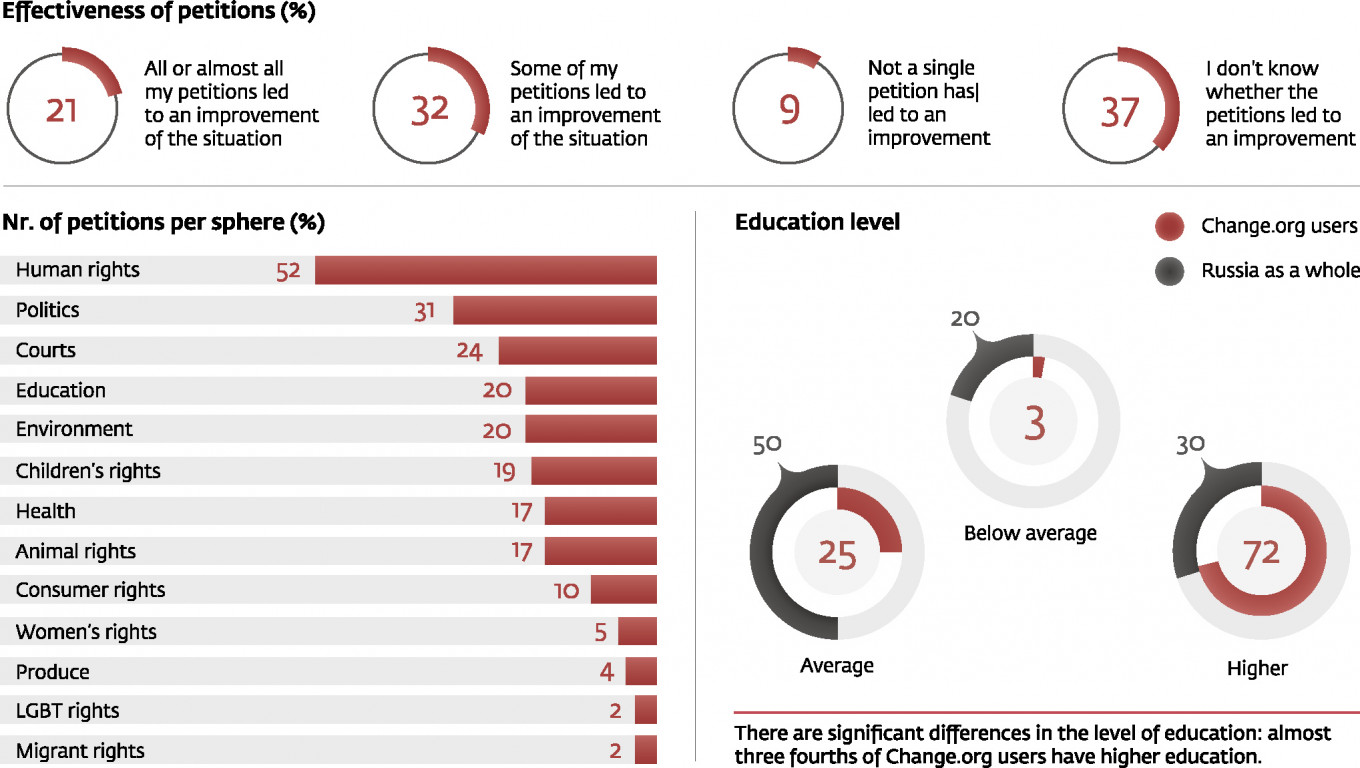

On average one petition every day in Russia is marked as successful, the second highest success rate worldwide, after the U.S. This is “proof that it's working,” says Savelau.

Many Russians believe so, too. Change.org's headquarters in San Francisco said this month its Russian-language site reached 10 million users — an impressive number considering it only came to the country in 2012.

The platform launched its Russian version for post-Soviet countries during a period of mass street protests against rigged elections and corruption in the Kremlin. It was a gamble, says Savelau: Would the company’s philosophy of grassroots civic action translate to Russia?

“The idea that you can communicate with your neighbors and your community and come up with solutions to problems yourself is entirely new in the former Soviet Union,” he says.

Now, an average 3,000 new petitions are uploaded to Change.org in Russia every month on complaints regarding health care, animal rights, the environment, and federal policies, in that order. Some want to clean up Lake Baikal, some want to stop a local school from being shut down, others protest Russia’s involvement in Syria.

As diverse as they are, however, they almost all have one thing in common: most are addressed to Russia's most famous problem solver, President Vladimir Putin.

That gives the petitions on the sleek website an anachronistic touch. “It's part of a much longer tradition of petitioning the Tsar to correct the misdeeds of local power holders that continued during Soviet times,” says political scientist and Russia expert Graeme Robertson.

Today’s Kremlin does its part to keep that ritual alive. Since 2001, Russians have been encouraged to send questions to an annual televised call-in with the president. The strictly choreographed show presents Putin as problem-solver-in-chief, and queries are solved with an efficiency that Russians rarely witness in everyday life.

Even before the show ended last year, two of the callers' complaints had been solved: A factory boss miraculously found millions of rubles to pay unpaid wages, while local authorities in the city of Tomsk began to fill potholes within minutes of a resident's complaint to the president.

Such direct appeals to Putin on matters big and small are “typical of states where power is highly centralized and institutional responsibilities are not well defined,” says Robertson. “Skipping to higher political authorities may be the only strategy that works.”

Part of Change.org’s mission is to wean Russians off this dependency on the ruler in the Kremlin, says Savelau.

“It’s fine if people ‘CC Putin,’ but we’re trying to tell them: maybe in between you and Putin there are other institutions directly responsible for your problem.”

A study conducted by the independent pollster Levada Center and commissioned by the platform shows that people who sign a petition are likely to take follow-up action, such as further petitions, meetings, or involving the media to draw attention.

“Petitions that help people develop broadly shared understandings of political problems and injustices could well be the beginnings of a broader political movement,” says Robertson. “Online activity may be particularly important in contexts like Russia where action on the streets is increasingly risky.”

That makes platforms like Change.org a force to be reckoned with by the Kremlin, says Yekaterina Schulmann, an expert on the workings of the Russian government.

“It’s a mistake to think the authorities don’t care about public opinion,” Schulmann says. With elections rigged, protests stifled and most media state-owned, petitions provide a rare mirror of what’s actually going on in Russian society — one watched anxiously by the Kremlin, she says.

In 2013, the government launched its own petitions platform, the Russian Public Initiative (ROI), which promises to send petitions that gather more than 100,000 signatures for review by a government-appointed committee.

In theory, that should make it a more effective platform than Change.org, which provides no such guarantee and has no links to the Kremlin. But only 13 petitions have passed the barrier, ROI told The Moscow Times. Only roughly half of them - on questions like limiting sound levels on TV ads, rules around switching mobile phone operators, and crosswalks — were “approved” and sent up the chain of command.

In Moscow, there is also the Aktivny Grazhdanin (Active Citizen) online platform which polls support for City Hall policies. But such government-initiated platforms have repeatedly been accused by critics of hijacking public opinion to rubberstamp uncontroversial decisions. That makes spontaneous platforms like Change.org all the more valuable — even to the rubberstampers, says Schulmann.

“The more you fence out the supposedly hostile and treacherous outer world, the more nervously interested you become in what is taking place there,” she says.

“I wanted my petition to become a real topic of discussion right away,” says Vadim Manukyan, the author of two Change.org petitions calling for caps on the salaries of Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and State Duma deputies.

Manukyan was not prepared to take his demand to the streets and risk backlash from law enforcement.

“This is the new format to deal with the Russian reality,” says Manukyan, who has a legal background. “Speak out, but stay within the bounds of the law.” He’s already seen an effect, with some of the deputies elected in September signing his petition and sharing it on social media.

Change.org has another benefit: signatories are not obliged to give their full details when they register. That inspires confidence in many Russians who are wary of retribution.

But the line is thin. The Change.org team must monitor petitions to ensure they don’t violate Russian laws banning the “promotion” of drug use, suicide, homosexuality or separatism. Patriotic groups meanwhile claim the platform's American roots make it anti-Russian.

“Our answer is: start a counter-petition!” says Savelau. Indeed, the platform contains many “patriotic” petitions, including calls for statues to Stalin and against a competition ban for Russia’s Paralympic team.

In Savelau’s eyes, that is precisely what makes it a success. “The point is to facilitate debate on issues that matter to people,” he says.

In today’s Russia, where the State Duma is widely seen as a puppet of the Kremlin, that might in itself be considered progress. That and, as Savelau says, “maybe one day people will no longer write to Putin if there’s a light bulb that needs fixing.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.