For Russia’s sports minister, 2016 is likely to go down as the most turbulent year of his life — and that is saying something.

With allegations of match-fixing and misspending surrounding Russian sports for years, Vitaly Mutko is no stranger to controversy. But the fallout from a report published late last year by the world’s anti-doping authority on an alleged state-sponsored scheme to cover up cheating by Russian athletes has been the most catastrophic by far.

On June 17, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) ruled that Russian track-and-field athletes would not be allowed to compete in the upcoming Olympic Games in Brazil's Rio de Janeiro unless they could prove they had not been “tainted” by Russia’s sport culture.

Add to that a meldonium ban that has affected dozens of Russian athletes, including tennis star Maria Sharapova, and a suspended disqualification for the Russian football team from UEFA following violence by Russian fans in France.

Russian sport is hanging by a thread. But while the storm rages on around him, the man at its epicenter is sitting tight.

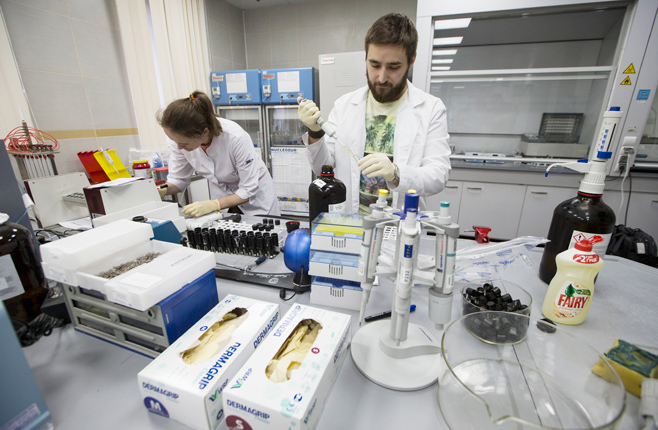

Employees working at the Russian drug-testing laboratory in Moscow in May 2016.

Smooth Sailing

Like many of those who climbed the Kremlin ladder under Putin, Mutko was alongside the president from the very start of his political career.

They met in St. Petersburg's City Hall, in the office of the city's liberal mayor Anatoly Sobchak. After a brief stint as a sailor, Mutko quickly rose up the ranks of local politics — reaching the position of deputy mayor in 1992. Putin at that time was head of the city's external relations department. In a sign of what was to come, the two men joined forces to organize the first international sports event held in Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1994 Goodwill Games in St. Petersburg.

After Sobchak lost a gubernatorial electoral bid, Mutko left City Hall to serve as president of the St. Petersburg Zenit football club in 1997. There, he proved his executive abilities. With Mutko at its helm, the club made it into the top three for the first time, and went on to win the Russia Cup in 1999. Mutko would later describe the time at Zenit as “the best years of my life.” But there was plenty of controversy too, with allegations of corruption and match-fixing.

Those rumors would continue to hang over Mutko during his time as head of the Russian football federation from 2005 to 2009. Editor of the Sports.ru website Dmitry Navosha says that Mutko’s contribution during this time was “not bad,” certainly when compared to his predecessors. But if anything, Mutko worked within existing structures, rather than push for reform and liberalization.

Mutko would remain a proponent of state involvement in sports throughout his career. In 2015, for example, he introduced a decree limiting the number of foreign players on the football field during match time to six. The move was widely contested by the clubs themselves but Mutko claimed it would serve national interests.

“Unlike in other countries, Russian clubs continue to be told what to do from the top and operate within a Soviet-era structure,” says Navosha.

Russia's Yelena Isinbayeva celebrates after winning the women's pole vault final at the IAAF World Championships in 2013.

The President's Man

When Putin was looking for someone to fill the position of sports minister in 2008, he needed someone he could trust. Mutko was that person.

“He is a typical product of Russia’s vertical hierarchy structure: 100 percent loyal to the leadership,” says Navosha.

Insiders, however, describe Mutko as not so much a civil servant as “a people’s man” with ties to athletes, coaches and fans. A man who hangs out with football players in the changing rooms after a match, a bottle of beer in hand, as recent photos from France show. Handouts, ranging from VIP tickets to football matches, according to an inside source spoken to by The Moscow Times, and cars for successful Russian Olympic athletes, seem part of his modus operandi.

“Mutko runs sports as if it were his personal company,” says journalist Konstantin Gaaze. “He knows everything about it, from top to bottom. He knows what trainer to hire, to fire. To whom to give money, and from whom to take it away.”

As sports minister, however, Mutko got off to a bad start. At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada, Mutko’s first big test, Russia failed to deliver, despite high levels of spending. With a total of 15 medals, only three of which were gold, it was Russia’s worst-ever Olympic performance.

Mutko’s already fragile position took another hit when an audit commissioned by then-President Dmitry Medvedev named him responsible for widespread misspending in the lead-up to the Games. It also revealed Mutko’s own exorbitant lifestyle at the taxpayer’s expense — for the 20-day Olympic event, he had claimed 97 expensive breakfasts. The total cost for his stay was $32,000, according to the audit.

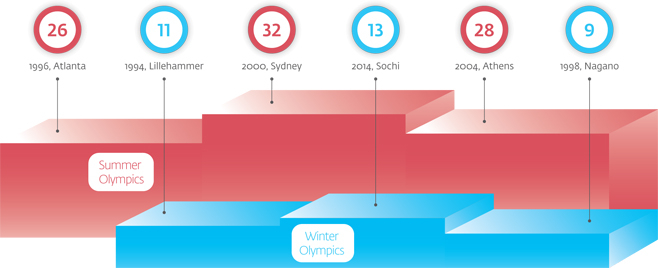

Russia's Olympic medal success

Many believed it was only a matter of time before he would be fired. But Putin’s Kremlin, however, was willing to give Mutko the benefit of the doubt. “The message was: Do whatever you want to do, as long as there are results,” says Gaaze.

If Mutko dropped the ball in Vancouver, he subsequently made up for it. In 2010, Russia secured the right to host the 2018 FIFA World Cup, in large part thanks to Mutko’s tireless personal lobbying. The minister also cultivated an image as an endearing, if somewhat clownish, figure.

His pronouncement of “Let me speak from the heart in English” in a heavily accented speech for Russia’s World Cup bid was widely ridiculed, but it made him more human.

More success followed in Sochi when the Black Sea resort was transformed into a world-class site for the 2014 Winter Olympics. Adding to the general euphoria, Russia topped the medals table that year.

But the success has not endured. Just this month, the national football team limped out of the Euro 2016 football championship, with many criticizing the players’ commitment.

FIFA has been engulfed in a sweeping corruption probe that has seen its head and former ally of Mutko, Sepp Blatter, removed. An investigation has also been launched into Russia’s successful, but questioned, World Cup bid.

Both Mutko, who sits on the FIFA Council, and Putin have jumped to Blatter's defense and deny any backroom dealings. Following his suspension, however, Blatter himself has told the media that the decision on where to stage the football tournament was a done deal before the vote took place.

Now, Sochi — Mutko's other success — has become the focus one of the biggest sports scandals in history. Russia might have won, but it cheated its way to victory, whistleblowers claim.

'Aware and Complicit'

In November 2015, the publication of a report from the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) shook the sporting world. The agency had uncovered a “deep-rooted culture of cheating” in Russian track and field, it said. The report described a state-sponsored doping program, requiring a concerted effort by sports coaches and athletics and anti-doping officials to conceal athletes’ positive drug tests. Crucially, the WADA probe said that the system could not have operated outside the knowledge of Russia’s sports ministry — and the man running it.

“It was impossible for him not to be aware of it. And if he’s aware of it, he’s complicit in it,” the chairman of the WADA probe, Dick Pound, said of Mutko’s involvement.

Mutko’s response has been mixed.

Initially, he dismissed WADA’s claims as politicized slander. As subsequent reports have confirmed and expanded on the initial revelations, including damning claims made by the former head of Russia’s anti-doping lab Grigory Rodchenkov, his tone has gradually softened.

In an editorial in the Sunday Times newspaper in May, Mutko admitted “serious mistakes” had been made by athletes, coaches and sports officials. Ahead of the IAAF ruling, he emphasized that Russia had reformed its athletics scene, including dramatic staff overhauls at the Russian anti-doping agency RUSADA and its athletics federation.

Veteran journalist Vladimir Pozner first interviewed Mutko in 2009, not long after his appointment as minister. At that time, Mutko lacked media experience, Pozner says. “He wasn’t very good at bringing across his viewpoint … He stumbled around a lot.”

To Pozner’s surprise, however, Mutko accepted a second invitation to appear on camera in a May interview. The minister didn’t behave like a man knee-deep in scandal, says Pozner. In fact, he “skillfully" responded to all questions with a combination of openness, calmness and cultivated confidence. “He had changed a lot,” says Pozner.

According to an anonymous source familiar with the situation, the doping scandal has called into question Mutko's position outside Russia. As controversy mounted, both the International Olympic Commitee and the IAAF have made unofficial requests to Putin to remove Mutko from his post as a sign of goodwill, the source said.

But a purge within the ranks of the Sports Ministry seems out of the question. Putin does not respond well to external pressure and will stand by Mutko just to prove a point, the source said, adding that Mutko also acts as a buffer for any claims of wrongdoing by his superior, Putin himself.

“Putin sees the doping scandal and everything around it as a political campaign against him personally,” says a different source with connections to a top official of Russia’s Olympic Committee during the Sochi Olympics. “He’s not going to give up Mutko.”

The question is how long that formula can hold — and at what price.

WADA will publish a second report into doping in Russia in July. In a recent preliminary statement, the chairman of the probe said the report would contain further evidence of the Sports Ministry’s hand in the doping probe.

And it's not just Russian athletics that should be concerned. In the days following the IAAF's ruling, media reports have alleged that two top Russian anti-doping officials had offered to stop testing Russian swimmers in return for cash in the buildup to the 2012 London Olympics.

While Mutko might succeed in clinging to his post thanks to his personal ties to the president, the recent scandals have been catastrophic to his international reputation. Few people would take at face value the image Mutko presented of himself during his first Q&A with Pozner in 2009.

What is your most valued attribute? Pozner asked then. “Decency,” Mutko replied. What do you hate most? “Lies.” And finally: What would you say if you appeared before God?

“I'm sorry if I did something wrong,” Mutko answered.

Contact the author at [email protected]. Follow the author on Twitter at @EvaHartog

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.