Picture the scene. It is 2016, oil costs on average $35 per barrel, and Russia’s recession rolls into its second year. The economy shrinks by 2-3 percent. Unemployment creeps up, and wages continue to fall, depressing consumer spending. The ruble devalues, driving up inflation. To keep price rises in check, interest rates remain high, discouraging investment. The government drains its reserves, hoping that the oil price picks up before they run dry.

This was the nightmare scenario painted by Russia’s Central Bank in its December research paper. The bank, and Russia’s federal budget, is still planning for average oil prices of $50 per barrel next year and an end to the recession by early 2017. But with the global oil market oversupplied and prices falling well below $40 per barrel, the likelihood of the pessimistic scenario is rising, the bank warned.

If that happens, Russia could face the first sustained cutbacks in government spending and falls in individual wealth since Vladimir Putin rose to power 16 years ago.

“We must prepare for difficult times,” said Finance Minister Anton Siluanov, whose budget relies for around half its revenues on taxes from the oil and gas industry. As the Central Bank published its research, Siluanov said oil prices could fall below $30 per barrel at certain periods, according to the TASS news agency.

Even if oil drops only to $30, the ruble, which falls in line with crude prices, would weaken to around 80 to the U.S. dollar, said Chris Weafer, senior partner with Moscow-based consultancy Macro Advisory. That would be 10 percent weaker than in midDecember and a devaluation of around 60 percent from two years ago, making Russians far poorer in dollar terms.

Not ready to face a $30 average oil price next year, the Finance Ministry instead mapped out the effect of $40 oil on the 2016 budget. It said state revenues would fall by 1.6 trillion rubles ($23 billion), or 2 percent of the country’s economic output, while the deficit would grow from 3 percent to 5.2 percent of GDP, or just over 4 trillion rubles ($57 billion).

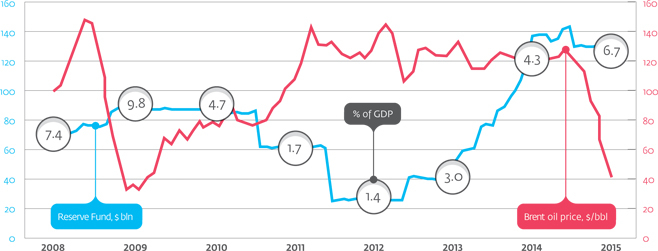

Drilling for prosperity: Oil prices and Russia’s Reserve Fund since 2008

To cover the shortfall, the ministry said the 4 trillion rubles amassed from oil exports in Russia’s Reserve Fund would be almost entirely spent by the end of 2016, according to the Vedomosti newspaper, which obtained a copy of the report. The plan also proposed a 5 percent sequester on spending across swathes of government.

That means the state would do less to offset the higher inflation, lower wages and shrinking output predicted by the Central Bank. And if the Reserve Fund is exhausted before oil prices rebound, the government would be forced to make deeper savings, and the number of victims of the recession would rise.

Poverty is already increasing. The economy is set to shrink by 4 percent this year, and official data show that over September to January, 20.3 million Russians, or 14 percent of the population, was below the poverty line—2.3 million more than in the same period last year.

So far, this has not stopped Putin’s ratings from rising to record highs thanks to a wave of patriotism and Russian military action in Ukraine and Syria. But parliamentary elections are scheduled for next year, and a presidential vote is set for 2018.

Prolonged economic hardship would influence a “fundamental change in attitudes toward the state” and support for the government would fall, said Vladimir Milov, head of the Institute of Energy Policy think tank in Moscow.

Aware of the social risks, the government is likely to cut spending, first and foremost, on infrastructure and investment, Weafer said. But this would undercut the foundation of any economic recovery, and as a result “the economy will be weaker for longer,” he said.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.