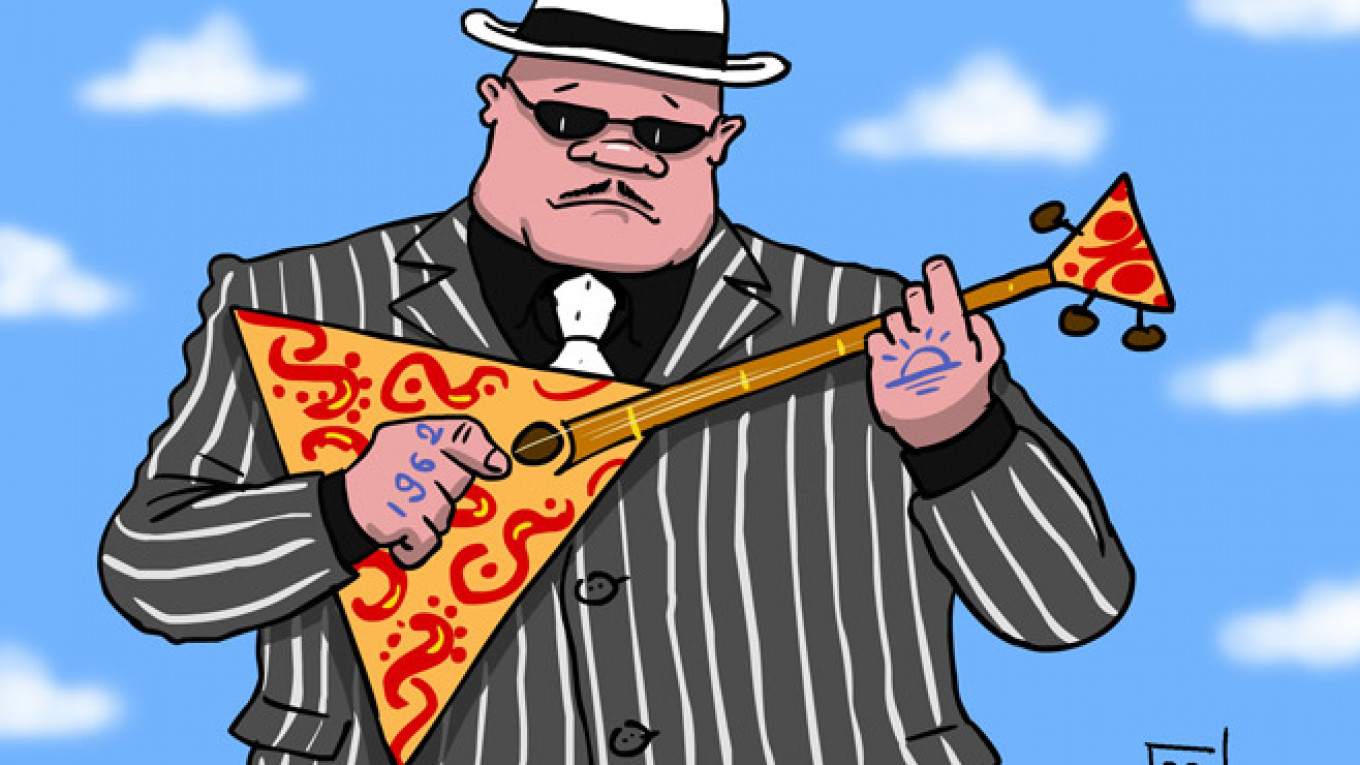

It probably reflects the current heightened tensions between Russia and the West, a time when many are willing to believe the very worst about Russians, that I have also noticed an upswing in queries coming my way about "Russian mafiosi." How powerful are they, how closely do they work with the state, how great a threat are they abroad?

The trouble is that often these are not Russians, and very rarely can they actually be considered a mafia. The clumsy stereotypes this demonstrates also says something about how the West sometimes gets Russia wrong.

Sometimes the gangsters are Russian passport holders, to be sure, but of non-Russian ethnicity. One such was Aslan Gagiyev, the North Ossetian gang leader arrested in Vienna on Jan. 17. Often, though, they are not even that — a "Russian mafia" in the United States or Europe, for example, will often turn out to be made up of Armenians, Georgians, Ukrainians or Belarussians. The official U.S. law enforcement term is now "Eurasian organized crime," but "Russian" is still widely used as a catch-all for everyone from Azeris to Uzbeks.

Not surprisingly, then, their relationship with the Russian authorities will also be varied and often conflicted. Russia undoubtedly has a serious problem with corruption, and the interpenetration of business, crime and politics. There is likewise evidence of, from time to time, active links between government agencies and organized crime. Many of the "self-defense forces" which cropped up in Crimea alongside the Russian "polite people" appear to have been drawn from the heavies of local gangs, for example.

Corruption is not a Russian monopoly, though. More to the point, the relationship is complex. Connections tend to be several times removed: A powerful businessman calls in a favor from a local governor, for example, on behalf of a client, who in turn is in bed with organized crime. It is not as if Russia's kingpins are lining up outside the Duma or the Kremlin with suitcases of cash and wish lists.

It also obscures the fact that law enforcement continues. Russia is not a country that can simply be characterized as a "mafia state." There are honest police officers and judges out there trying to do their jobs, even if admittedly not always in favorable conditions. The arrest of the aforementioned Gagiyev, for instance, followed a joint operation between the Russian and Austrian authorities.

Then let's consider that troubling word "mafia." There is a whole criminological literature on what distinguishes a "mafia" from other forms of organized crime, but in general use it has all kinds of implications.

A "mafia" is a close-knit gang, a ruthless hierarchy with a godfather at the top, his lieutenants below and foot soldiers at the bottom, like some underworld army. There is mistrust, but also loyalty, maybe some kind of code of behavior, honor among thieves.

Frankly, you'd be hard pressed to find this within much Western organized crime these days, but Russian organized crime is even more postmodern. The big organizations, such as the infamous and transnational Solntsevo, are loose networks of local gangs, criminal businessmen and autonomous groups that form and reform as opportunities open and close.

The days of the thieves' code, of strict adherence to the ponyatiya ("codes") are long gone. Especially among ethnic Russians, only essentially local — city, town or neighborhood — gangs retain any strong hierarchical basis.

So talk of the "Russian mafia" then says several things about how the West looks at Russia, especially now.

It tends to assume homogeneity where there is actually bewildering variety. All of Eurasia is still too often "Russia" and a range of different criminal actors, operations and subcultures are treated as one and the same.

Second, it reinforces a notion that whatever comes out of Russia and Eurasia is somehow specially and uniquely dangerous. Yes, organized crime in the region is violent and vicious, but set alongside the gangs of Mexico or Brazil, the Italian Camorra or the American MS-13, they might almost seem models of decorum.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it sees organization and long-term strategy where there is often just anarchy and opportunism.

This is also very much a theme of Western perspectives on current policy, especially on Ukraine, where the usual cliches — such as Putin the "chess grandmaster" or the "judo black belt" — are deployed to present the Kremlin as a sinister strategist.

In the West we have no problem seeing our own leaders as hapless victims of events, grasping at ad hoc measures to avoid tough and unpopular decisions, or driven by prejudice and simplistic assumptions. Yet somehow we tend at the same time to ascribe deeper, subtler and more deliberate designs to our rivals.

At a time when there is a widening gap between Russia and the West, it is comforting to use every opportunity to demonize the other side. But just as in the West we are dismayed to see glib and inaccurate talk of "Nazis" and "imperialists" being mobilized by Russian nationalists, the idiom of talk of the "Russian mafia" demonstrates a degree of caricature on the other side, too.

Mark Galeotti is professor of global affairs at New York University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.