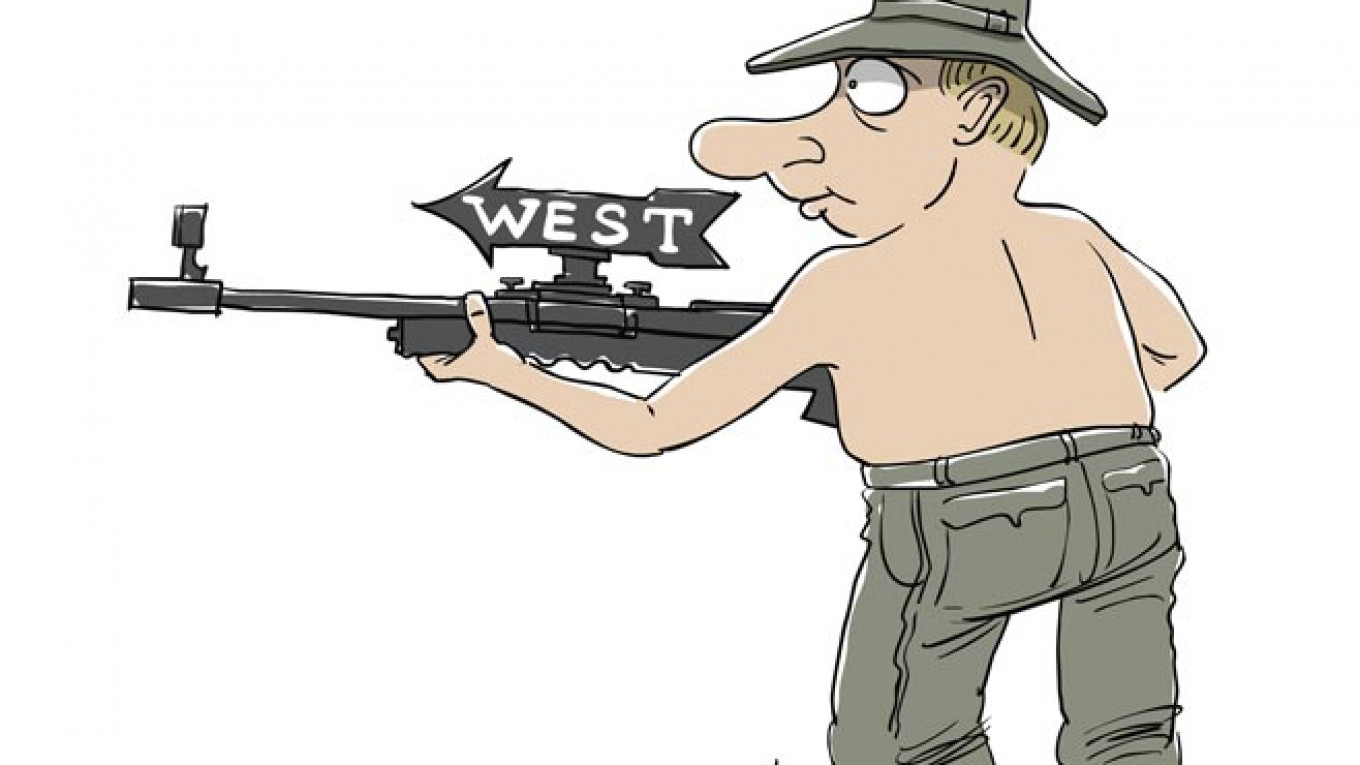

Russia and the West entered February surrounded by uncertainty — frustrated and angry with the other side but still ready to explore an admittedly fraught path forward. They exited March unexpectedly locked in a new cold war, the ambiguity gone, and the other side transformed into an undisputed adversary with plans underway to deal with it as such. Russian aggression sent them reeling into this other world, but over the years they had prepared the way together.

The new cold war will be between Russia and the West, not an international affair, but it will affect the entire global arena.

The new cold war will be different from the original. It will be a cold war between Russia and the West, not a global affair, though it will profoundly affect the entire international political system. It will not have the last one's ideological impulse, although the political animus now congealing will substitute. And it — let's hope — will not play out under the dense shadow of nuclear Armageddon.

Some will add that, unlike the original Cold War, it also will not really matter, given Russia's fundamental weaknesses and relative insignificance compared with a surging China and the scale of other challenges facing the U.S.

They are wrong.

Dealing with the Russia-West relationship in fundamentally adversarial terms will contaminate nearly every critical dimension of international politics, seriously warp U.S. and Russian foreign policy and exact a heavy price in lost opportunities.

Rather than redefine NATO to better address new security challenges, the old NATO will be reinforced and pressed closer to Russia's borders. Despite its economic limitations, Russia will answer in kind. Defense planning in Washington and Moscow, which were both in the process of adjusting to more modern, 21st-century threats with diminished resources, will come under irresistible pressure to spend on old threats that are driven by fears copied from the original Cold War.

Any thought of salvaging a crumbling arms control regime in Europe, reducing tactical nuclear weapons, cooperating on missile defense or taking the next steps in controlling strategic nuclear weapons — let alone, the first steps toward managing an increasingly unstable multipolar nuclear world — now becomes pure fantasy.

Russia-West energy relations, vexed but key to the global energy economy, will take on an unadulterated geo-strategic dimension. Violence, when it erupts, say, between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, in Central Asia or, worse, in Ukraine will tempt nervous adversaries to intervene against one another rather than work with one another to contain it. Dealing with vast new challenges, such as the rise of China, will be done competitively rather than cooperatively.

In the face of this new reality and given its immense costs, the overriding guideline for U.S. and Russian policy should be to make the new Russia-West cold war as short and shallow as possible. The pressures on both sides, however, push in the opposite direction. In the U.S., the tendency will be to rest policy on regime change — that is, only when President Vladimir Putin is gone can we hope to build a different relationship with Russia — rather than aim for a change in regime behavior. In Russia, the tendency already is to give up on the U.S. and its European allies and focus on rallying others to a jaundiced view of where Western policy is taking the world. In a throwback to the original Cold War, the emphasis on both sides will be on "winning this new contest" rather than on managing, then defusing and ultimately surmounting it.

In the mature, later phases of the original Cold War, management, rather than victory, came to dominate, and elements of cooperation — the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaties in the 1970s, the space station and the reunification of German in 1990 — merged with moments of dangerous tension, such as the 1973 Yom Kippur War, turmoil in the Horn of Africa and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. And then it was over.

Success for the U.S. blended credible strength with a readiness to engage. It also depended on the growing realization that mistrust between the two sides mattered as much as the other side's malevolence; that the pathologies in their interaction contributed as much as the pathology in the nature of the other side; and that Soviet behavior was more determined by events than by predetermined plans or genetic code. In the end, U.S. policy was wiser in shaping events than in trying to shape Soviet character.

Sad as it is, we are arriving at this point because Russia and the West wasted the "peace dividend" that was awarded to them by the end of the original Cold War, only to have to learn again the lessons of that costly rivalry.

Robert Legvold is Marshall D. Shulman Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Columbia University and author of "Russian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century and the Shadow of the Past."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.