"If you can't measure it, you can't manage it." That is the wisdom behind adopting metrics like gross domestic product and other aggregate indicators that signal the health of national economies around the world. Policymakers and planners have used these numbers for decades to help them understand how to guide domestic economic growth.

But reliance on GDP and other traditional indicators may be sabotaging a keenly sought goal: the development of thriving innovation economies. Today, some vital parts of the information-technology sector barely register in the national accounts.

While GDP measures the market value of all goods and services produced within a country, many stars of the digital age — think Wikipedia, Facebook, Twitter, Mozilla, and Netscape — produce no goods and provide free services.

These same star players also tend to undercut the productivity of traditional businesses. Free navigation apps have shrunk sales for Garmin, the GPS pioneer that was once one of the fastest-growing companies in the U.S., while Skype is killing the international phone call "one minute at a time."

These developments point to the need for new growth metrics that recognize new kinds of enterprise. Since these metrics concern innovation, they should be forward-looking as well. Policymakers need to understand how to establish, manage and thus measure the conditions that encourage innovators to flock to a region and forge a prosperous future there. Innovation metrics must capture the value of new ideas years before those ideas become profitable in traditionally measured ways.

The need for such metrics is especially urgent in the developing world. Emerging economies commonly use foreign direct investment, or FDI, as a yardstick to measure progress. That metric makes sense in the early stages of development: poor economies need foreign capital to build factories, train workers and put money in the pockets of ordinary citizens.

But foreign investment most often goes to low-risk, low-margin projects: iron foundries, cement plants, and so forth. Innovation, by contrast, is a high-risk, high-reward effort. Even big multinationals do not put a lot of money into a new idea at first. Tomorrow's most disruptive innovation may have no effect on FDI or GDP today.

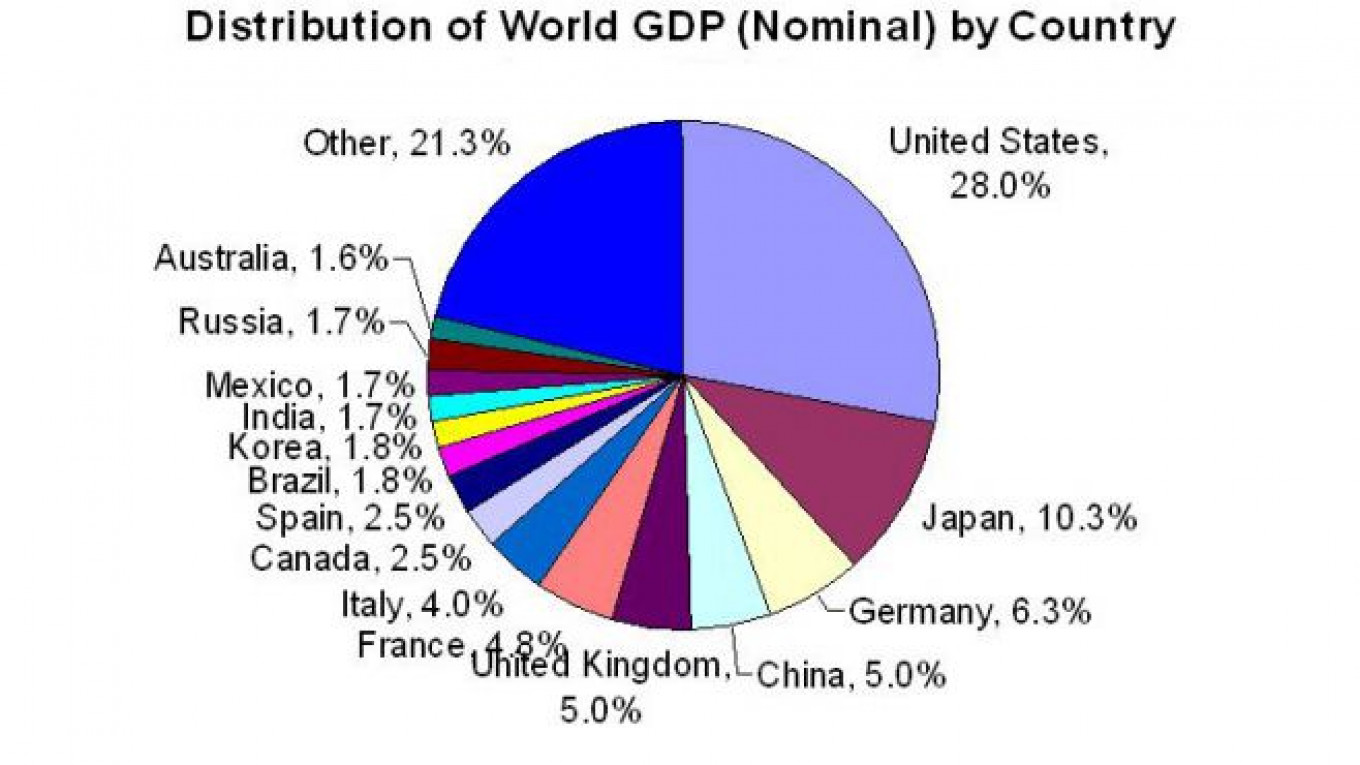

Thus, for countries like China, India and Brazil that are trying to jump-start their domestic innovation cultures, FDI targets actually prevent government planners from reaching out to the people and companies that are most likely to take creative approaches to problems.

So what does valuable innovation look like, in terms of macroeconomic data, years before it gives rise to the next Google, Bayer, Porsche or Alibaba? What numbers best characterize a thriving innovation ecosystem in its birth stages?

We already know some of the essential ingredients. They include top-level talent, serial entrepreneurs with good track records, startups backed by reputable capital and breakthrough products protected by intellectual-property rights. Analysts that I work with recently investigated whether these ingredients could be quantified. Our preliminary results suggest that they can.

For example, we learned that five of today's most successful startups in the information-technology sector had two attributes in common by the end of their third year in business: they had filed more than one patent and been funded by more than one top venture capital firm. In subsequent years, these five companies' cumulative revenue was six times higher than that of startups chosen at random.

Economists could extend such analyses to develop a set of key performance indicators for young innovation economies. Governments could then use these innovation metrics to identify startups, talent and products with the strongest potential for future success. This approach could be applied to any high-tech incubator project — within or beyond the developing world — that currently measures success only in dollars.

Of course, such metrics would merely improve the odds of succeeding, not point to a sure thing. Innovation economies will always require investments in a multitude of prospects to produce the few big winners that will ultimately anchor the mature ecosystem. But even a modest improvement in odds will deliver outsize results if it means landing two Apples or Samsungs rather than one — or none.

Changing how we think about economic value will not be easy. Yet countries where GDP has been flagging — an ever-increasing cohort — might welcome new metrics that can show signs of real progress. And there is a growing awareness among policymakers and planners that virtual assets like creative talent and entrepreneurial skill make up an increasing portion of a country's wealth.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis acknowledged as much last summer when it changed the definition of GDP to better represent the contributions of intellectual property and research and development to productivity and economic vitality.

Broader efforts to reform GDP, including initiatives sponsored by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the European Commission, seek to encompass sustainability, living standards and other important aspects of a country's wellbeing. In addition, groups like the Institute for New Economic Thinking are championing the study of innovation economics to provide data and analyses for these efforts.

As former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke noted in a 2011 speech, "We will be more likely to promote innovative activity if we are able to measure it more effectively and document its role in economic growth."

In fact, metrics that help countries drive innovation could change our very understanding of economic growth. Governments want them, economies need them, and the global community will benefit from them. It is time for macroeconomics to measure up to the ambitions of 21st-century innovators.

Edward Jung, former chief architect at Microsoft, is chief technology officer at Intellectual Ventures. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.