The presidential election on March 4 was crucial for Russia, a country that many observers believed was on the brink of a "color revolution." There are three important lessons that can be learned from the election.

First, with Vladimir Putin reinstalled as the new-old president, he becomes solely responsible for everything that may happen to the country. This comes at a time when the potential for economic growth and political stability is nearly exhausted.

Five years ago, I wrote a comment in Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper in which I supported a third term for Putin. At that time, I was aware that he may step aside for four years — particularly in 2007 as the global economic crisis was just beginning to take shape — and later come back as a savior of the nation. Now, with the consequences of the crisis clearly visible, Putin must cope with the country's economic problems directly as he returns to power. So we will see how the master who orchestrated the current Russian political system can manage it in difficult times. I believe that he will not be successful.

Second, the presidential election showed that Russians are tired of the same old candidates. Communist leader Gennady Zyuganov, who has led the party for nearly 20 years, may still try to hang on for a few more years, but more likely he will be replaced by a younger politician well before the next election cycle — perhaps Sergei Udaltsov, 35.

This clearly reflects major changes in the Russian political map since the mid-1990s and may result in a major regrouping on the left of the political spectrum. If this leads to a formation of a modern social democratic party on the base of both the Communist Party and A Just Russia, it may open a new era in Russian politics, one that is better equipped to meet the country's social needs.

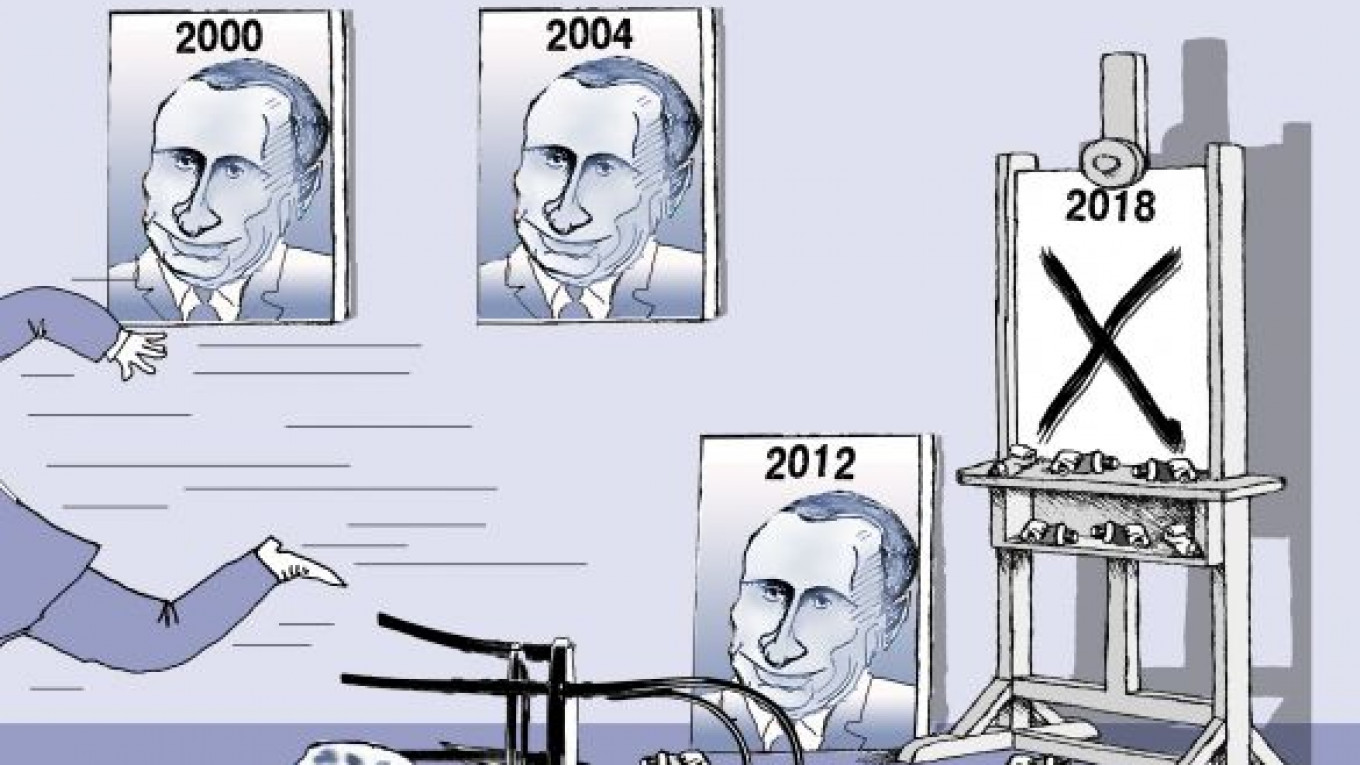

Third, billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov received nearly 8 percent of the vote — perhaps 16 percent if you consider the votes that he would have likely received if there had been no ballot-stuffing. Prokhorov's success refutes many of the myths about Russian politics. It shows that Russians do not hate oligarchs as much as they used to, that the memory of the "wild '90s" is fading, and that they desperately want a new political figure who answers to the needs of a rising middle class. Prokhorov's success was caused not so much by his personal capacities but by these new aspirations. If he does not make any major mistakes in the years ahead, he may very likely become the leading presidential contender in 2018.

Russia's political landscape is now clearer than ever before. We have a national leader who denies responsibility for the crumbling system he created. We have rivals who proved unable to attract enough votes to win. And we have Prokhorov, a young, dynamic and accomplished businessman who may be able to unite the middle class and to turn it into the most vibrant and influential political force in the country, despite the fact that liberal-democratic values up until now never really served as a unifying force in Russian politics.

What is in store for Russia in the near future? I don't believe that Putin will change his mode of governance. In many respects, he has driven himself into a corner. Having labeled many members of the opposition as Western-funded secret agents, Putin can't very well sit down at the same table and negotiate with them. Moreover, he cannot manage the economy if there is not enough petrodollars coming in every month to feed the appetites of the corrupt elite.

It would be terribly naive to expect a softer and gentler Putin 2.0 emerging in the next six years. Instead of making unrealistic demands, the opposition should let Putin's system falter on its own. But this doesn't mean it should sit and wait idly. It should switch its focus from organizing street protests to building new political structures. Those opposing Putin both from the left and right should now focus on constructing two new parties — one on the left and the other on the center-right, somewhat resembling Democrats and Republicans in the United States. This would help squeeze out the amorphous center now occupied by the pro-Putin United Russia.

The opposition should also take advantage of the new legislation proposed by outgoing President Dmitry Medvedev to ease registration requirements for new political parties and widen the number of direct elections in the country. Newly registered parties could run in mayoral and gubernatorial races, and they could play an important role in shaping regional legislative assemblies. Their main task should be to prepare themselves for national campaigns in 2017 and 2018. At the same time, they should drop the incendiary, unattainable demand that Putin step down from office before 2018.

New freedoms and democracy will not come overnight. They must be won in a long battle that should be fought within the framework of the law.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is a professor of economics at the Higher School of Economics, director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies and editor-in-chief of Svobodnaya Mysl.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.