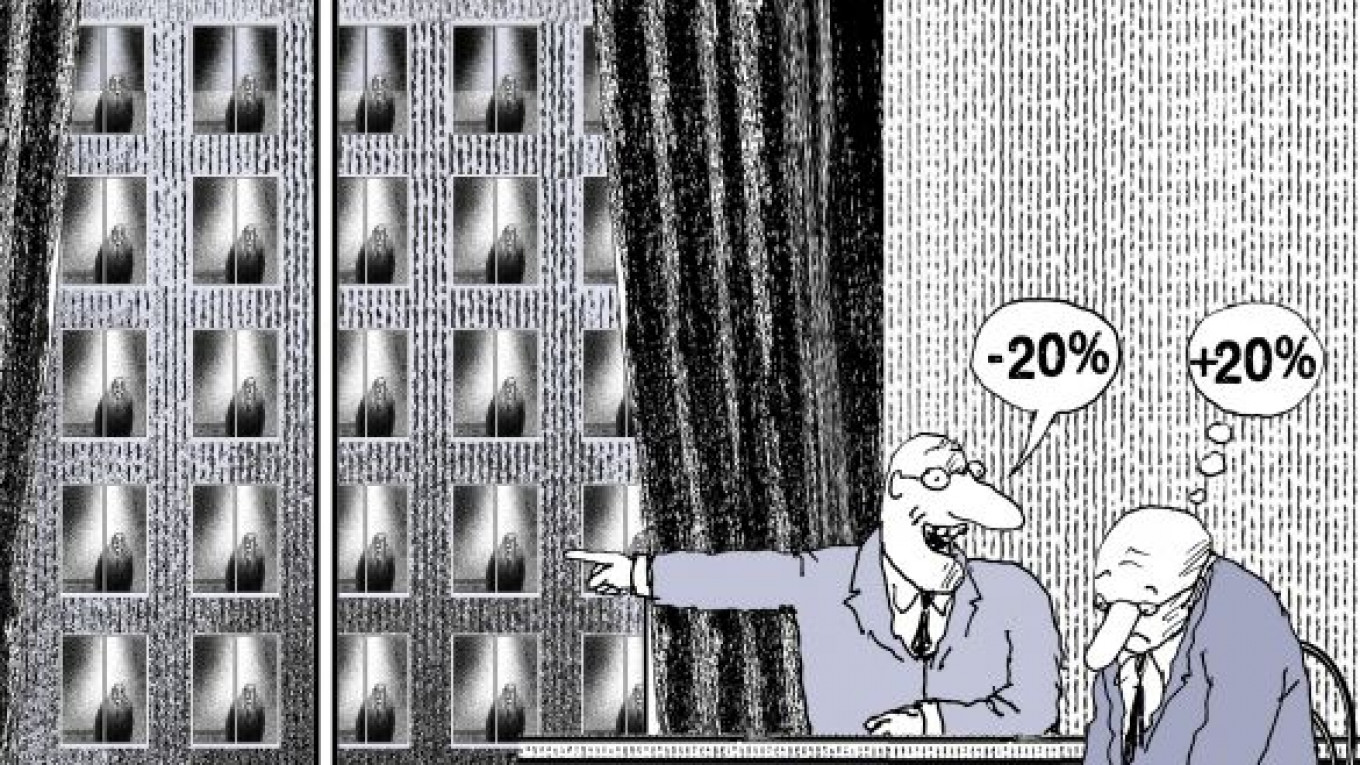

With great fanfare, President Dmitry Medvedev has announced his intention to slash the bureaucracy by 20 percent. It is a bold attempt to deal with an unmanageable government apparatus, perhaps the chief cause of the country’s persistent economic problems. It is also profoundly mistaken.

The push to shrink the Russian bureaucracy is founded on two myths. The first myth is that the bureaucracy is unusually large. The second is that larger bureaucracies necessarily impede private economic activity. There is no empirical support for either proposition.

The myth of the mammoth Russian bureaucracy has its roots in an undisputed fact: The government is largely corrupt and inefficient. It does not immediately follow, however, that the bureaucracy is corrupt and inefficient because it is too big. Indeed, the Russian bureaucracy is quite small by world standards, even after substantial growth in recent years. Consider these numbers: In 2009, public administration employment at all levels of the Russian government accounted for 2.5 percent of the employed labor force. By comparison, public administration in members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, constituted on average 9 percent of the labor force in the early 1990s, according to the single available cross-national study of government employment. Indeed, there was not a single OECD country with a smaller bureaucracy in the early 1990s than Russia has today.

Of course, the more appropriate comparison may be with Russia’s peers among developing and transition countries. Yet even by this standard, Russia’s bureaucracy appears small. In the early 1990s, the typical post-Communist bureaucracy accounted for more than 4 percent of total employment — far smaller than in the wealthy states of the OECD, but larger than Russia’s today. As to the high-performing developing economies that are Russia’s foremost competitors for international capital, the bureaucracy in China was close to 3 percent of total employment in the early 1990s, and in Turkey close to 4 percent. However one slices the data, Russia’s bureaucracy does not look large.

Surely, the argument goes, any bureaucracy can be cut to the benefit of private economic activity. This is the second myth behind the Kremlin’s ill-considered drive. Without a concomitant push to cut red tape, shrinking government employment may leave entrepreneurs even more at the mercy of venal public servants. If it’s hard for a private firm to get a license or permit today, imagine what it will be like when the line backs up because of staff cuts. Desperate to get to the front of the line, owners and managers will be even more tempted to grease the wheels by providing side payments to those with the authority to make or break their businesses. Alone behind the counter, Russian bureaucrats will be like store clerks in a Soviet establishment: all power and no responsibility.

This is no mere theoretical possibility. Our research with David Brown of Heriot-Watt University, based on the statistical analysis of data from numerous Russian firms, suggests that precisely this dynamic was at work during the first decade and a half of the post-Communist economic transition. Our analysis takes advantage of large variation across regions in the size of the Russian bureaucracy. After stripping away the effects of other factors — population, urbanization and the like — what is left is regional patterns of public employment that appear to be rooted in Soviet-era development priorities.

Therefore, Russia offers a sort of experiment by which the effects of bureaucracy on private economic activity can be estimated. First, public servants actually appear to work more responsibly and honestly in regions where bureaucracies are relatively large. Firms in those regions report spending less time and money acquiring licenses from the state, and they pay smaller kickbacks for government contracts. Second, private firms are more productive (relative to state enterprises in similar industries) in regions with relatively large bureaucracies. With a less-hostile state apparatus, private-enterprise owners and managers face fewer constraints when taking actions that raise their productivity — for example, seeking out new markets, laying off redundant employees, starting new product lines and so forth.

The proposal to cut Russia’s bureaucracy is a misguided solution to the wrong problem. The country’s problem is not that its bureaucracy is too large. It’s that the bureaucrats it does have aren’t responsive to the people they serve. There are no easy solutions to that problem, but concentrating power in the hands of a few state officials runs the risk of making the situation worse, not better.

John Earle is professor of public policy and economics at George Mason University and professor of economics at the Central European University. Scott Gehlbach is associate professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.