MINSK — In the aftermath of Belarus' presidential election, a 3-year-old boy is at the heart of a battle with a secret service that still calls itself the KGB.

Lyutsina Khalip is fighting to keep her toddler grandson Danil out of an orphanage after the secret police jailed his parents, a journalist and an opposition presidential candidate who had challenged President Alexander Lukashenko.

The repression of this family is part of a broad campaign to punish Lukashenko's opponents and crush all dissent. After winning a fourth term last month, Lukashenko unleashed the KGB against the opposition in a chilling echo of the Soviet era.

"Lukashenko is trying to frighten Belarussian society, to plunge it into fear," said analyst Alexander Klaskovsky. "And for this he is using tried and true methods from the 1930s — repressions, arrests and searches."

About 700 people, including seven of the nine opposition candidates, were arrested on election night when police brutally dispersed mass protests in central Minsk against what international observers agreed was a rigged election.

Most were held for 10 to 15 days and released. But more than 30 people remain in jail, including the little boy's parents: presidential candidate Andrei Sannikov, who finished a distant second to Lukashenko, and Irina Khalip, an international award-winning journalist who writes for Russia's Novaya Gazeta newspaper.

In the weeks since the Dec. 19 protests, KGB officers have searched the homes and offices of journalists and rights activists across the country, seizing computers and files. A popular radio station that had given airtime to Sannikov was closed down.

Even ordinary people have been ordered to show up for questioning after cell phone providers gave police the records of all calls made in the vicinity of the election-night protests, according to some of those called in for questioning and police.

Lukashenko has never tolerated much dissent during the more than 16 years he has ruled. But the current crackdown is drawing direct comparisons to the repressions of the Soviet era. The threat to take away little Danil Sannikov has been particularly alarming because it is so reminiscent of the Stalinist practice of putting the children of so-called enemies of the people in orphanages when their parents were sent to the gulag.

"The terrible Stalinist times are returning to Belarus. I can't believe that this is really happening," said Lyutsina Khalip, 74, clutching her grandson to her chest.

She and her husband, film director Vladimir Khalip, believe that the government is using the boy to put pressure on their daughter and son-in-law.

"The attempt to take our grandson is a vile way of putting pressure on our daughter, an attempt to force her to do what Lukashenko wants," Vladimir Khalip said by telephone from a hospital, where he has undergone two eye operations in recent weeks.

Political analyst Valery Karbalevich said such use of children was a standard tactic, pointing to past cases of grown children being jailed to pressure political opponents.

"By using children they are able to get their opponents to confess, to capitulate politically, to appear on state television and make a repentant speech," he said.

That seems to be one of Lukashenko's goals. Presidential candidate Yaroslav Romanchuk, who was not arrested, denounced the protest organizers on national television in a clip shown repeatedly for several days.

"Some people from the presidential administration came to see me and made me read a text," Romanchuk said later. "They told me that this would save the lives of several of those who were arrested."

The elder Khalips have had no word from their daughter since she was arrested. All they have is a quick note she was able to write asking her parents to take care of Danil and saying she loved him very much. She and their son-in-law face charges for their role in the protests that could keep them in prison for up to 15 years.

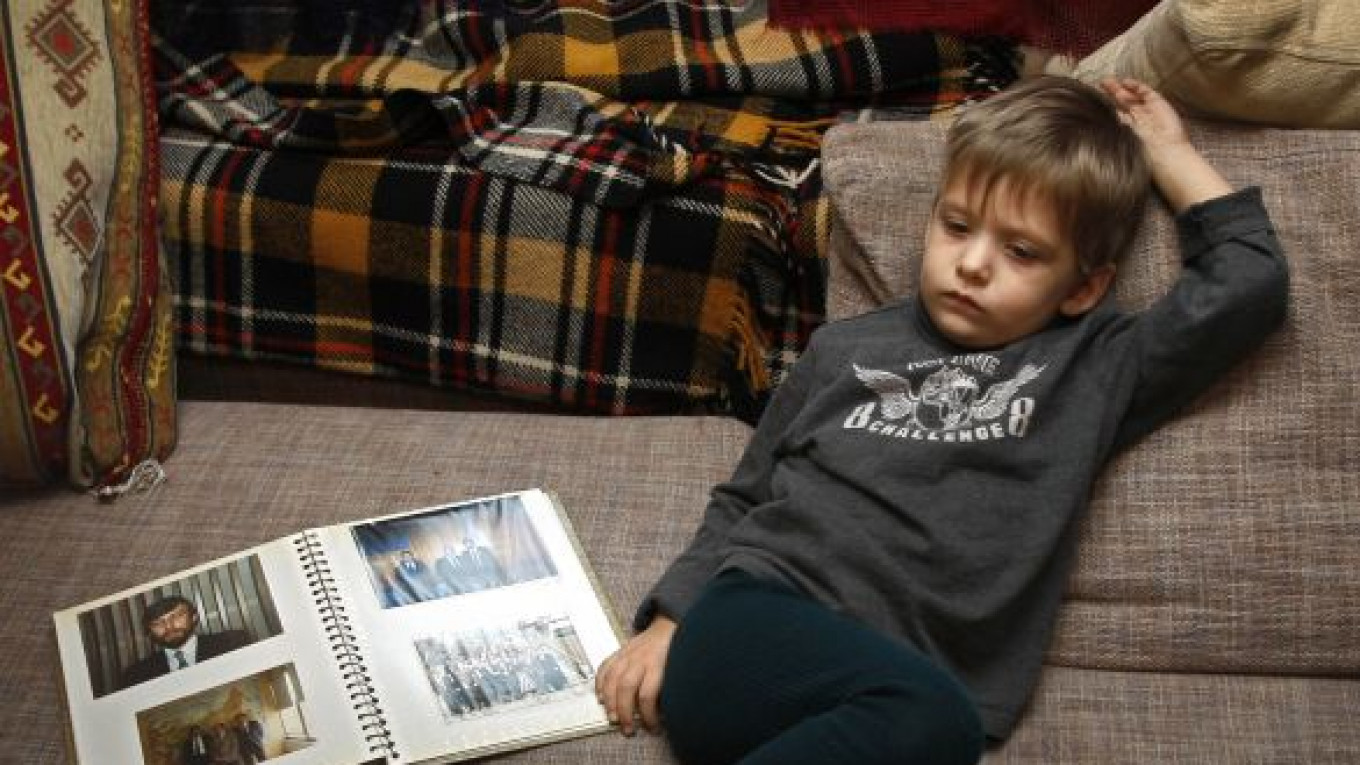

Danil now spends his days playing in his room, which is full of toys brought by visitors in a show of support for the family.

His grandmother has kept him at home ever since government social workers tried to take him from his kindergarten during a New Year's show. She was at the KGB jail that day attempting to pass warm clothes to her daughter and son-in-law when she got a phone call that sent her rushing back to the kindergarten.

There she was met by two social workers who said they were checking on the welfare of the boy and showed her a document from the KGB ordering the check. They gave her until the end of the month to prove she was fit to care for Danil.

Lyutsina Khalip has applied for legal guardianship, which involved going through a medical examination. Both she and the 3-year-old boy were tested for hepatitis, syphilis and HIV.

"All this is being done to humiliate us as much as possible, as if we were not a happy family but homeless and living at a train station," she said.

The social worker in charge of Danil's case said many factors would be taken into consideration.

"We cannot yet say whether the grandmother will be given guardianship or whether Danil will be better off elsewhere," Antonina Drugakova said. She confirmed that the case was opened after her agency was contacted by the KGB.

The pressure on Khalip increased last Wednesday when KGB officers showed up for a fourth search of her daughter's apartment, where she now lives with Danil, and took her in for questioning, followed by a search of her own apartment, the second since the election.

The KGB then ordered Khalip to sign an agreement not to reveal any details about the searches or interrogation. Lawyers representing jailed candidates and journalists have had to sign similar documents.

The questionable vote tally for Lukashenko and the ensuing persecution of his opponents have drawn an array of denunciations from the West, which had hoped that Belarus would follow through on promised reforms.

The United States and European Union have called for the immediate release of those arrested, and the EU has threatened to reimpose sanctions, including a travel ban on Lukashenko and other officials.

The West has been eager to lure Belarus out of its quasi-Soviet patterns of political repression, human rights abuses, lack of independent broadcast media and a largely state-controlled economy. The EU offered Belarus 3 billion euros ($4 billion) in aid if the elections were judged free and fair.

Lukashenko had appeared to be toying with taking the aid, and had even sharply criticized traditional patron Russia during the campaign. But his tone changed after Moscow agreed to eliminate tariffs for oil, giving a big boost to an economy that has grown dependent on cheap energy supplies from Russia.

"In Belarus for now they aren't shooting people," said Valentin Stefanovich of the rights group Vesna. "But the KGB has revived the entire Stalinist arsenal of means of dealing with dissidents."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.