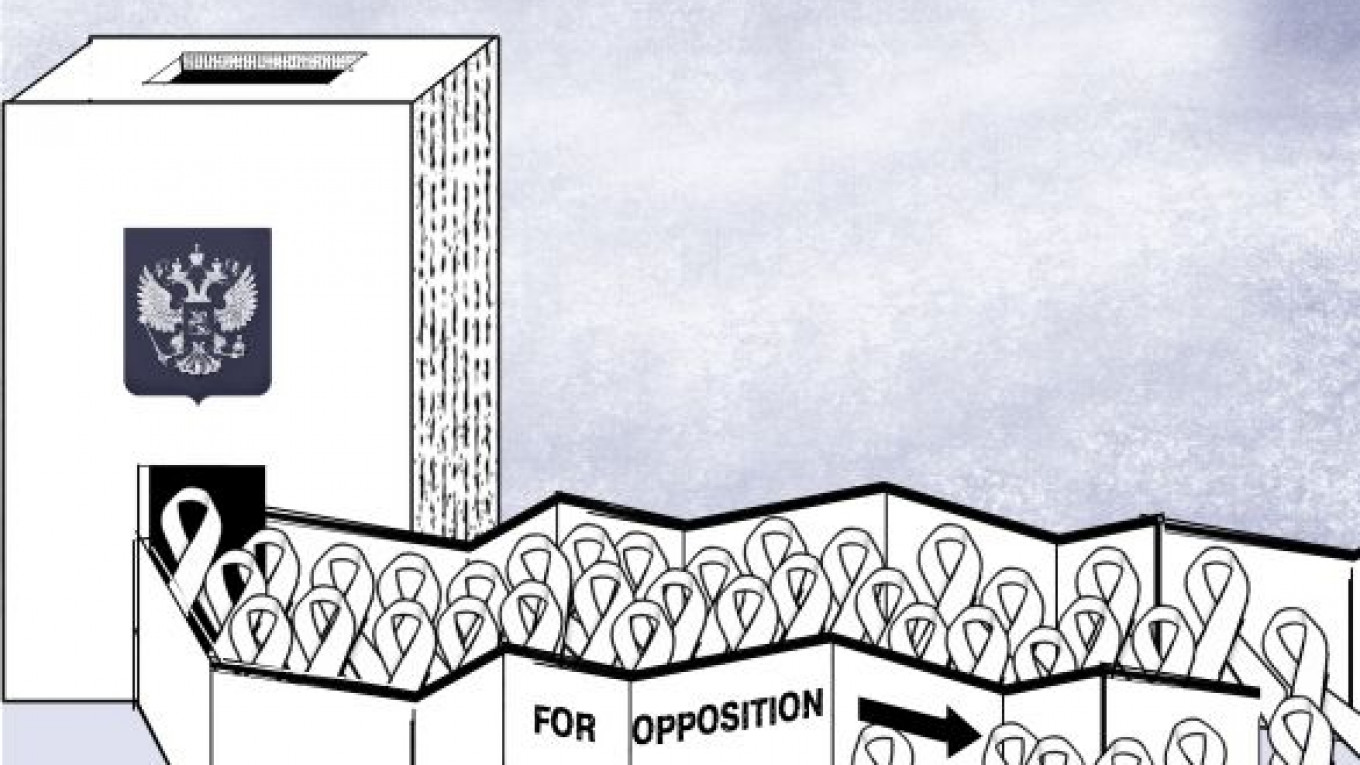

Regional elections in October will be a test for the "nonsystemic" opposition that staged mass protests from December to May. In theory, that movement has an opportunity to use concessions offered by the authorities that give them greater involvement in the political process. How ready is Russia's opposition to enter the political arena in a serious way?

Right now, the greatest opportunity for an opposition figure to gain public office is in the Moscow suburb of Khimki, where former Mayor Vladimir Strelchenko was recently pressured into resigning by Sergei Shoigu, the governor of the Moscow region. On Strelchenko's watch, there have been numerous assaults and beatings of environmental activists and a record of rampant corruption gone unpunished. The worst conflict was a clash with the grassroots movement that opposes the construction of the Moscow-St. Petersburg highway, which will cut right through the Khimki forest.

Now Yevgenia Chirikova, a leading figure in the nonsystemic opposition, announced that she would like to run for the mayoral post in Khimki. She already ran for mayor in Khimki once before in a dirty election that was tainted by fraud. Strelchenko had originally lost the race, but the ?µlections ??ommittee met behind closed doors for a recount, after which Strelchenko was announced the winner.

Chirikova's bid for mayor has received the rare support of the Yabloko party, as well as the Parnas party and State Duma Deputies Ilya Ponomaryov and Gennady Gudkov from the Just Russia party. But Just Russia leader Sergei Mironov said the party would put forward its own candidate in the race. That move makes it a spoiler, splitting the protest vote and fulfilling the very function for which the Kremlin created an "official" opposition.

It seems that the authorities will be a little more flexible in their tactics for the fall regional elections. At least Shoigu has made it clear that the opposition will face less discrimination during this campaign. The plan might be to let a real opposition candidate like Chirikova compete in an election that voters perceive as being more or less competitive and honest. Authorities may be prepared to recognize the actual results of election if they are sure that the United Russia candidate will win anyway.

Indeed, there are solid grounds to bet on United Russia victories in Khimki and in other regions. The authorities have made great efforts over the last six months to discredit the nonsystemic opposition. In recent months, several opposition figures were given the chance to speak on talk shows on state-controlled television, where it was a simple matter to edit and manipulate the footage to cast them in a bad light, and even to make complete fools of them. State-controlled media outlets were purposely fed leaks discrediting opposition members — for example, tapes of their private telephone conversations, compromising photographs or huge stashes of cash discovered in police raids.

At the same time, the opposition has done its own share to discredit itself. The opposition will hold something akin to a primary to elect a 45-member coordinating committee, but ordinary people have little understanding of how the candidates are put forward, and information about the election is practically unavailable outside of a few remote Internet sites. Moreover, disaffected Russians are tired of the same old faces in the opposition camp. The demands and slogans shouted at large rallies were unrealistic from the outset and have since been largely forgotten. What's more, the opposition has been inactive over the summer, allowing their flame to be extinguished, at least for the time being.

To make matters worse, the opposition has been linked to one degree or another to the Pussy Riot punk rock group, which in the eyes of most Russians is considered radical and eccentric, if not freakish. And despite the opposition's excuse that it does not endorse the group's protest methods and only sought a more lenient sentence for the women, the argument is lost on most conservative voters. They continue to view members of the opposition as spoiled Muscovites who run about the city's central squares wearing white ribbons and shouting anti-Putin slogans while lacking any understanding of the more difficult and often despondent lives of provincial Russians.

Now the opposition must convince dismayed voters that it has been misunderstood and that it has a program for action that includes reforms at the municipal level. Opposition leaders must prove that they are not demons with horns but ordinary, honest people who can be trusted to hold public office. The main task before the opposition is to find a common language with the public so that voters will believe that its leaders are a new and different type of politician ?€” public servants in the Western sense of the word ?€” whom Russia needs to modernize.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.