The Russian army has just started its spring call-up, and the top brass report that they plan to put 153,000 young men in uniform before it is finished. This time the rules for the draft are significantly tougher. In the past, all graduate students were automatically exempted from duty. Now, only those studying in specific fields known only to military officials will be overlooked. According to Defense Ministry representatives, even writing a graduate thesis paper in one of the specified subjects is no guarantee of an exemption.

That bureaucratic hairsplitting contradicts recent statements by Defense Ministry officials. For example, Deputy Defense Minister Nikolai Pankov said during an interview with Ekho Moskvy radio that Russia's 130-year-old system of conscription is hopelessly outdated. "I think it would be wrong to try to maintain the status quo," Pankov said. "We have no choice but to find new ways of accomplishing compulsory military service."

What's more, Pankov was highly skeptical of the idea that graduates should be conscripted, stressing that many do not return to their chosen professions after their release from the army.

Acting under President Putin's impossible orders, the armed forces must pretend that people who would normally do everything in their power to avoid the draft are actually serving in the military.

The top brass clearly disagrees on this issue. Some Defense Ministry officials firmly contend that the draft is fundamental to staffing the armed forces. In their opinion, the main problem is that the population is so unreliable because more than 230,000 young men never respond to their draft notices. At the same time, other ministry officials argue that the draft is hopelessly obsolete and that recruiting students is unwise at best.

The reason for the confusion is that President Vladimir Putin gave the Defense Ministry an impossible task — to staff a million-man army even while Russia is slipping into a demographic black hole. To reach the million mark, it would be necessary to draft 550,000 to 600,000 conscripts annually. However, only 600,000 young men turn 18 each year, and by some estimates the number is less than 500,000.

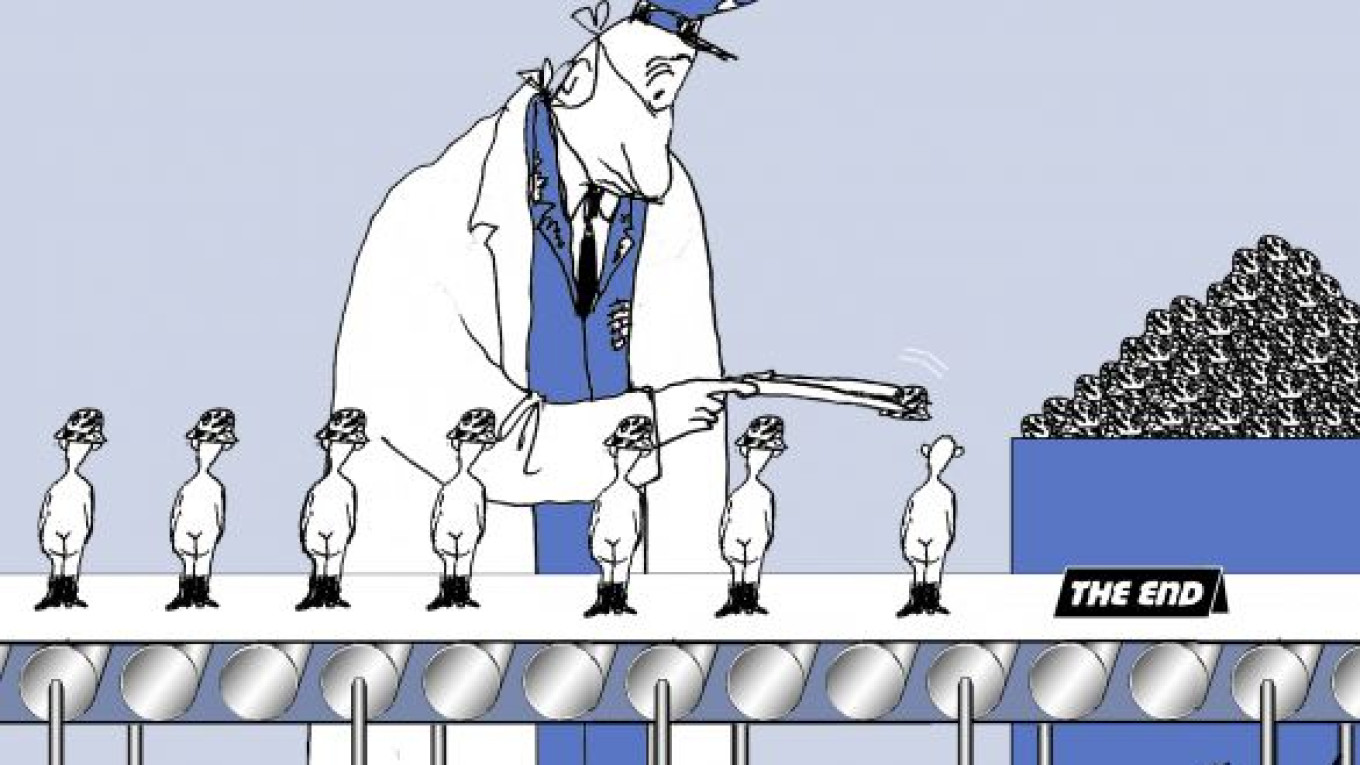

Under these circumstances, the military bureaucracy is split. Some are relying on draconian measures such as the threat of prison to corral draft dodgers into active duty, while other, more progressive officials are looking for new approaches. Thus, the rectors of several universities have proposed — clearly at the Defense Ministry's urging — that university students fulfill their year of obligatory military service in three annual stints of three months each. Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu has gone even further, proposing the creation of "academic squadrons" in the same spirit as the "athletic squadrons" in which world-class Russian athletes ostensibly serve. According to Shoigu, the new squadrons would be staffed by "talented young men who, without leaving their universities, will carry out, in cooperation with their professors, tasks required by the Defense Ministry." And it turns out that the ministry is ready to "finance the research and development activities of such groups."

These innovations all sound very serious and high-minded with their promise of training effective reserve forces and improving the quality of military service. But they will obviously do nothing to enhance Russia's security. Both the proposal to allow students to serve "on the installment plan" and the idea of creating "academic squadrons" are meaningless. It is unthinkable that anyone could master the skills required for military service in three separate sessions spread out over three years. It would be similarly impossible to expect a scientific discovery or development of any use to the military to come from a university student who serves in an "academic squadron" for one year. Only top-tier universities can carry out the research needed to build modern weapons: That work cannot be carried out on orders from a sergeant major.

For the first time in history, the interests of society coincide with the interests of one part of the military establishment. Because Putin has given the military the impossible task of staffing a million-man army, the only solution for the top brass is to fudge the numbers. To do that, they must pretend that people who would normally do everything in their power to avoid the draft are actually serving in the military. It would seem that the Defense Ministry is prepared to do just that — by offering them a nominal form of service in "athletic" and "academic" squadrons, as well as the opportunity to study at a very leisurely pace in several three-month stints. In this way, many of those thousands of draft dodgers would be able to legalize their relationship with the Russian government.

Of course, it would have been better if Putin had simply ordered the armed forces to maintain an army of 650,000 to 700,000 men and to make the transition to a fully professional army by 2017 — the date by which the army expects to have 425,000 contract soldiers. Add to that 220,000 officers, and the result would have been a modern Russian army.

Unfortunately, Russian leaders believe it is necessary to have a million-man army — even if it is only on paper. That means it is already approaching a shortage of 270,000 men. So why not simply record the missing soldiers as doing duty in an "academic" squadron instead? That is one possibility, but it is just as likely that the advocates of more forceful measures will win out. In that case, the Defense Ministry would lure potential conscripts out of their ivory towers and into standard fighting units, with guns and uniforms in place of pens and lab coats. The State Duma is already considering a bill that would make military service obligatory after the second year of college.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.