American-Russian businessman Peter Vins says he could have apologized for calling the policemen who raided his company "bandits" and seen his legal problems limited to a $10,000 fine.

But Vins, a former Soviet dissident, refused and now faces up to six years in prison on tax evasion charges.

“Why should I apologize when even Medvedev and Putin are calling them this?” Vins said, referring to criticism of the notoriously corrupt police force by President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

“I want to win this case even though my business is near bankruptcy,” Vins said in a telephone interview from Riga, Latvia, where he is living after his supporters, who include several prominent human rights activists, advised him to stay away from Russia.

Vins' tale covers familiar territory for many investors who have sought to do business in Russia over the past two decades. But what makes his case unique — and a possible litmus test — is that it is unfolding at a time when the Kremlin has declared war on corruption amid a series of embarrassing incidents involving corrupt police officers.

Vins, son of Soviet Baptist minister Georgy Vins, immigrated with his family to the United States in the late 1970s but returned to Russia in 1993 and opened the VinLund logistics company the following year.

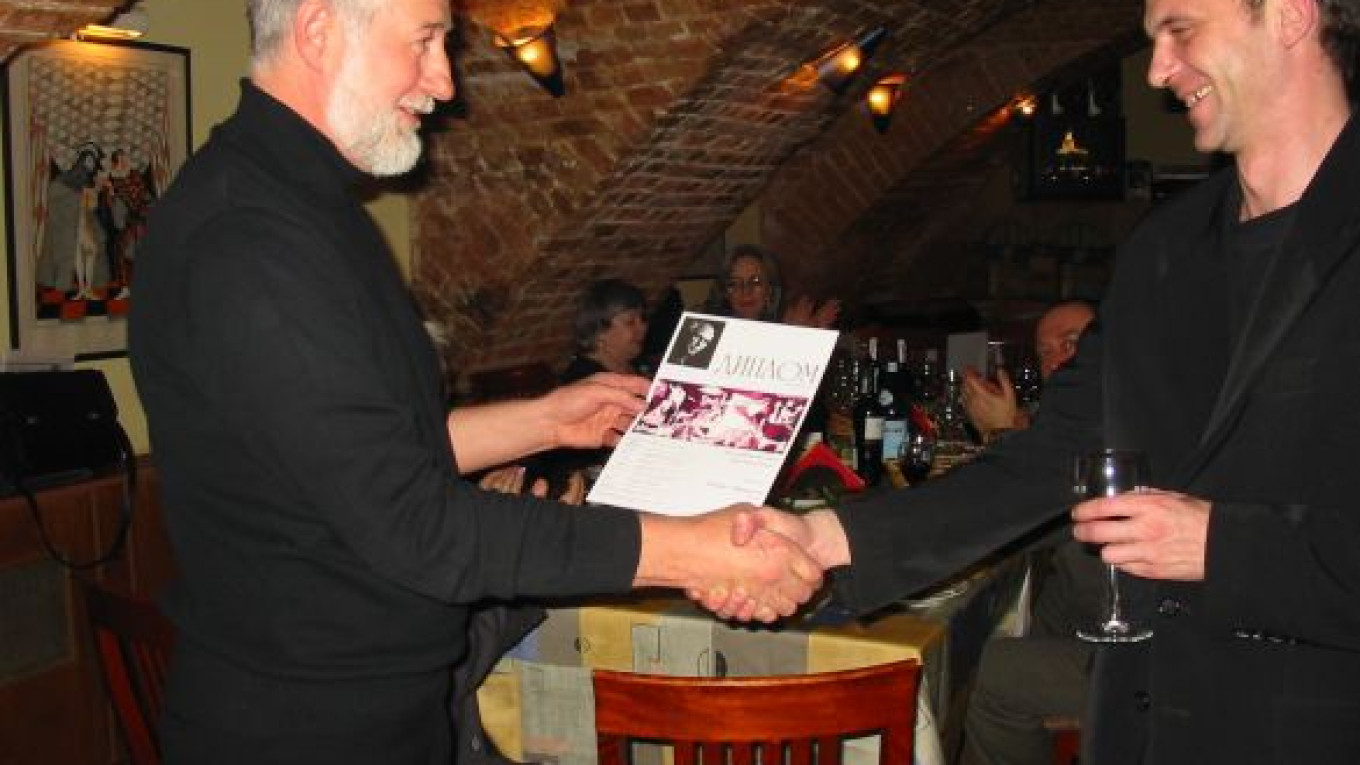

Vins also holds extensive human rights credentials. He is a former member of the human rights organization Moscow Helsinki Group and the founder of an Andrei Sakharov prize for investigative journalism. The Vins family had been close to the family of the nuclear physicist and human rights champion, and in 2000 Peter Vins established the $5,000 award called, "For Journalism as an Act of Conscience."

VinLund, meanwhile, expanded and prospered in the turbulent 1990s and more stable 2000s, attracting clients such as the French carmaker Peugeot and U.S. farm equipment producer John Deere.

But everything changed in September 2007 — five months before Medvedev first declared war on corruption and six months before he was elected president.

Plainclothes detectives raided VinLund's Moscow offices in a search that mystifies Vins to this day. He said the crackdown might have been connected to his human rights work, ordered by a business rival or simply routine police work.

The detectives accused VinLund of working with companies that existed only on paper and of providing false accounting data to the tax authorities. While Russian law does not require a company to check the legitimacy of another company before teaming up with it, the Supreme Arbitration Court encouraged such checks in a 2006 ruling. If a front company disappears, its tax problems become the problems of its partners.

Vins said the detectives did not identify themselves, behaved rudely, and one of them wrapped his hands around the neck of a female VinLund lawyer who tried to snap pictures of their leader with a cell phone.

“They behaved like criminals,” Vins said.

Vins only learned that the men were officers with the Moscow police force's economic crimes department after he filed a complaint with the Moscow City Prosecutor's Office shortly after the incident. He said he received a reply that his company was clean and could continue its work.

But in September 2008, Vins received another visit from officers with the economic crimes department. They acted politely, Vins said, and collected documents describing VinLund's relations with clients.

Two months later, however, Vins was notified that one of his companies stood accused of transferring money to the accounts of nonexistant firms. In August 2009, a criminal case was opened against Vins on charges of evading $100,000 in taxes. At the police's request, the Moscow City Court issued a warrant for Vins' arrest in September.

The court is scheduled to consider an appeal against the arrest warrant in February, Vins' lawyer Olga Strizhova said. If it upholds the warrant, the police will put Vins on Interpol's international wanted list.

Vins fled Russia in late 2008, fearing revenge from police officials after he publicly complained of police harassment.

What prompted Vins' ordeal — like many disputes between investors and the authorities — is a matter of speculation.

“My understanding is that he is being punished for making this case public,” said Boris Timoshenko, a representative of the Glasnost Defense Foundation, a Moscow human rights watchdog that awards the annual Sakharov prize established by Vins.

More than 100 cases similar to Vins' were opened under the same article of the Criminal Code in Moscow in January 2009 alone, said Pavel Larin, a lawyer with the Nalogovik consulting group who is unaffiliated with the Vins case.

“Inspections of a business by tax and law enforcement officials are often used to pressure the head of the company," he said. "But their nature might not be just economic, but political, too."

Incidentally, Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer for William Browder's Hermitage Capital who died in a pretrial detention center in November after being denied medical treatment, had been charged with the same article of the Criminal Code as Vins.

Vins has written two letters to President Dmitry Medvedev in which he maintains his innocence and explains that he has tried to fight injustice “with legal methods.”

In one letter, he wrote that police investigator Sergei Tsibulin made him an offer before he sent his case to court: that he would get off with a fine of 300,000 rubles ($10,000) if he returned to Moscow and apologized for describing Russian policemen as "bandits" in his letters to the media and Russian officials.

Tsibulin, reached by cell phone Monday, refused to comment on Vins' claim or the case.

Other representatives of the Moscow police's economic crimes department also declined to comment on the case, citing the ongoing investigation.

Sakharov’s widow, prominent human rights activist Yelena Bonner, urged Medvedev in an open letter earlier this month to intervene. Bonner said she was writing the letter "in the name of Sakharov, who for many years defended Peter Vins, his father and mother."

Bonner, who lives in the United States, also wrote that she had advised Vins not to return to Russia in order “not to repeat the fate of Magnitsky,” the lawyer who died in detention.

Strizhova, Vins’ lawyer, hopes that new amendments to the tax and criminal law that went in effect this month might help her client. The amendments increase the size of a tax claim that can be classified as “particularly massive fraud” to three times the amount that Vins is accused of owing. Therefore, Vins is now charged, on paper at least, with committing a lesser crime, punishable by a fine alone and without prison time. The new amendments also allow judges to place people suspected of tax crimes under house arrest instead of in pretrial detention facilities.

Vins said he just wanted to get back to work and reach out to the many clients who have fled amid his problems with the police. “I hope we will continue to do business in Russia,” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.