Yury Grishankin never imagined his business could be destroyed so quickly. At the end of last year, the mid-level property developer’s portfolio boasted eight retail premises, all of which he had built himself.

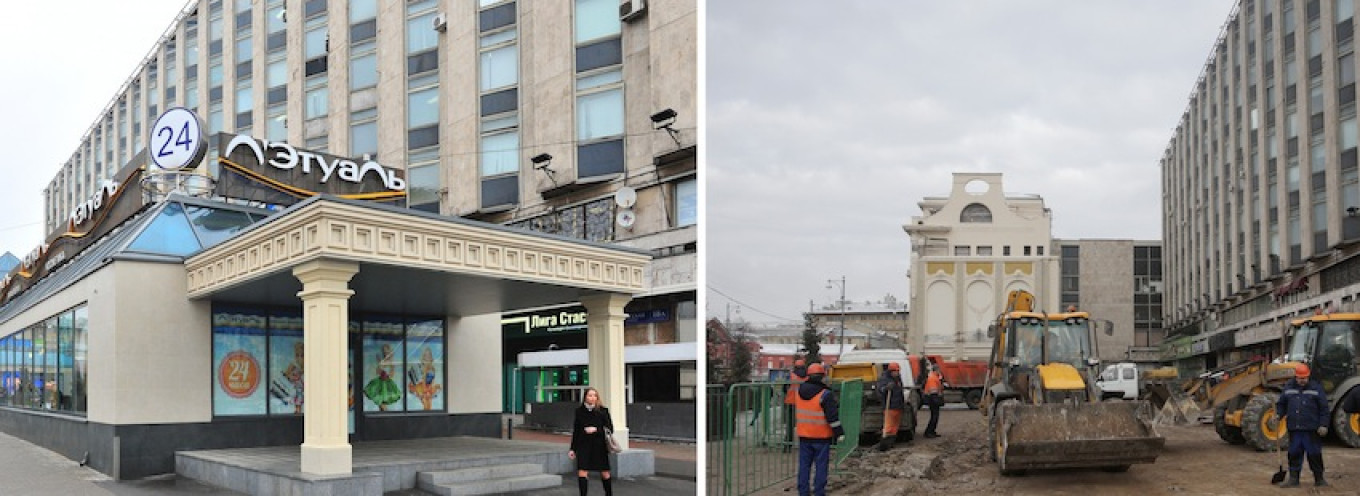

His problems began when Moscow City Hall included one of the properties in a demolition list of so-called “illegal constructions.” On one February night, the property was bulldozed along with 100 other pavilions and kiosks. The move sparked massive public outrage. The owners argued that they had all the necessary paperwork for their properties. Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin was unwilling to listen, and said in a VKontakte post that this paperwork was “obviously acquired illegally,” and the owners cannot “hide behind” it anymore.

The statement sent a clear message to small and mid-level businesses: If the authorities decide to go after your real estate, documents offer no protection.

Grishankin has been told that another six of his buildings have been included on a second demolition list, and will be razed in the coming weeks.

“I will end up with only one building,” says the businessman with a sad smile. “They claim the buildings were illegal — but over the years I’ve won court cases, including in the Supreme Court, proving the opposite.”

Grishankin has decided to strike back, and sue City Hall for damages his business suffered after the February demolition. He has demanded 1.8 billion rubles ($28 million) in compensation, and his case is now being heard by the Moscow Arbitration Court.

“I don’t even want the money as much as I want to show that it is not right — to treat us like this,” he says.

Winning Battles, Losing the War?

On the face of it, Grishankin should have a case. When he built his now demolished two-story retail pavilion near a metro station in southern Moscow in the early 2000s, he received all the necessary permits and a lease on the plot of land the building occupied. The building was constructed on utility lines of the Moscow metro, and metro officials offered him a deal: They would approve construction if he paid for the renovation of those utility lines. “Which I did — that was the condition of getting a permit from them,” Grishankin says.

At the first hearing of the case in the Arbitration Court, his lawyers used this to undermine one of the authorities’ main claims — that having buildings on metro utility lines is dangerous and illegal.

In 2006, Moscow authorities took Grishankin to court for the first time. In their lawsuit, they argued that the pavilion was an “unauthorized edifice” and needed to be demolished. The court ruled in Grishankin’s favor, refusing to deem the building illegal and rejecting City Hall’s demolition request. A second attempt to prove in court that the building was illegal took place in 2013. Several months before the authorities compiled the first demolition list — in October 2015 — the developer once again won the case. As before, the court refused to authorize demolition and declare the building illegal, citing expired statutory limitations.

“After all those court cases I sighed with relief and thought my business was safe,” Grishankin says. “When the building appeared on the demolition list [in December 2015], I tried to contest it, to explain to authorities that I have all the documents. But then they just showed up at night with bulldozers.”

There was no warning that day, and the tenants of the building barely managed to remove their belongings before the bulldozers got to work. “That very day I went to meet with the municipality head, to submit a complaint about potential demolition. She didn’t say a word, but at 1 a.m. she showed up at the building, along with two buses of riot police officers,” Grishankin says.

Within seven days the building was entirely dismantled.

Second Round

Grishankin’s six other buildings are yet to be demolished. He plans to contest the decision in court, but has little hope of succeeding. Like with the destroyed pavilion, City Hall had tried previously to go after at least three of these buildings in courts, going all the way up to the Supreme Court. In December 2014, the latter sided with the developer, confirming earlier rulings that stated the buildings were not illegal. And yet they have found themselves on the demolition list — along with more than 100 others.

Grishankin’s experience is not exclusive. Several owners of other buildings from the second list polled by The Moscow Times told almost identical stories. They had all the necessary documents, City Hall had sued them, but failed. “I won a court case 18 months ago,” says one owner of a pavilion, asking to speak anonymously. “The court agreed that my building was not illegal. It is a nice-looking pavilion that fits the surrounding architecture, and several small retailers rent space in it.”

The businessman says he plans to try to contest the decision to demolish his building in court, but is convinced that at the end of the day all the structures will be demolished. “If it’s demolished, I’m done — I don’t have any other businesses. Many of my tenants will lose their sources of income, too,” he says.

Another owner, also speaking on conditions of anonymity, told The Moscow Times he won three court cases against City Hall. “These rulings were quite an encouragement for us. The courts are on our side, we thought! We even carried out an expensive renovation of our building,” he says. “And then they made our day by issuing this new list.” When asked whether he plans to engage in a legal battle with City Hall about this, the owner expressed doubts that such a campaign could be successful.

“It’s a wall you just can’t break through,” he says.

Cutting a Deal

Grishankin’s fight for compensation has a long way to go. So far there has been just one, preliminary, hearing. But City Hall has already made it clear that it will be a difficult fight for him to win.

Legally, a developer is entitled to reimbursement for damages caused as a result of a government’s illegal actions. Yet Moscow officials argue their actions were completely within the law, in that they were outlined in a decree signed by the Moscow mayor, the legitimacy of which was confirmed by the Supreme Court in April. Grishankin’s lawyers maintain that demolishing a building that was properly documented and authorized was illegal nonetheless.

The only compensation city authorities are ready to offer to all the owners is the cost of demolition works — if owners carry them out voluntarily and on their own.

It might be, in fact, the best way to go now, says Alexei Petropolsky, a lawyer defending several owners of demolished buildings. “If you want to get something out of it, either demolish your building yourself, or sell your business before it’s too late,” Petropolsky told The Moscow Times. “You can try to take it to arbitration court, but, given that it is vacation season, legal proceedings would take time. By the time the judgement is in, they’d have already destroyed everything.”

Several property owners are rumored to have cut a deal with Moscow authorities. “We worked with owners of the four buildings that went up to the Supreme Court, trying to argue that the first demolition list and Moscow government decree outlining it were violating the law,” Yaroslav Volpin, spokesman of the Association of Real Estate Owners, told The Moscow Times. “City Hall negotiated with all of them, and they ended up settling — some of them for cash, some of them for apartments in Moscow.”

Head of the Moscow department for trade and services Alexei Nemeryuk said he could not confirm this information to The Moscow Times. “The Moscow government, as far as I know, has never paid any compensation. Moreover, there haven’t been any applications,” he said.

Constitution Games

The Moscow City government has based its actions on an article of the Civil Code that was introduced last year, allowing local authorities to demolish constructions built on utility lines without going to court. But this article was intended to target illegal buildings — those built without documents, property rights, permits. Lawyer Petropolsky accepts that such properties are fair game — local authorities can decide and demolish it on their own. But property with contracts, documents, permits, lease agreements, is a different matter and needs to be settled in court. “The Constitution clearly states that no one can be deprived of their property without a court ruling,” he says.

In April, several State Duma deputies from the Communist Party filed a request to the Constitutional Court to establish whether the article itself contradicts the Constitution. The ruling is yet to be made, but the Association of Real Estate Owners sent a letter last month to Russian President Vladimir Putin, urging him to postpone the second round of demolition until the ruling is in. Earlier in June, Putin himself tasked the authorities with improving the legislation that regulates demolition of illegal buildings. He even gave them a deadline — Dec. 1.

City Hall is still, however, planning to carry out the second round of demolition. “They are basically challenging the president,” says Volpin.

Disillusionment has become the main sentiment among entrepreneurs. “We built our businesses from the ground up. No one taught us, and we had to learn everything as we went,” says Grishankin. “Now it simply hurts to see all of that in tatters. No one wants to start anything new.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.