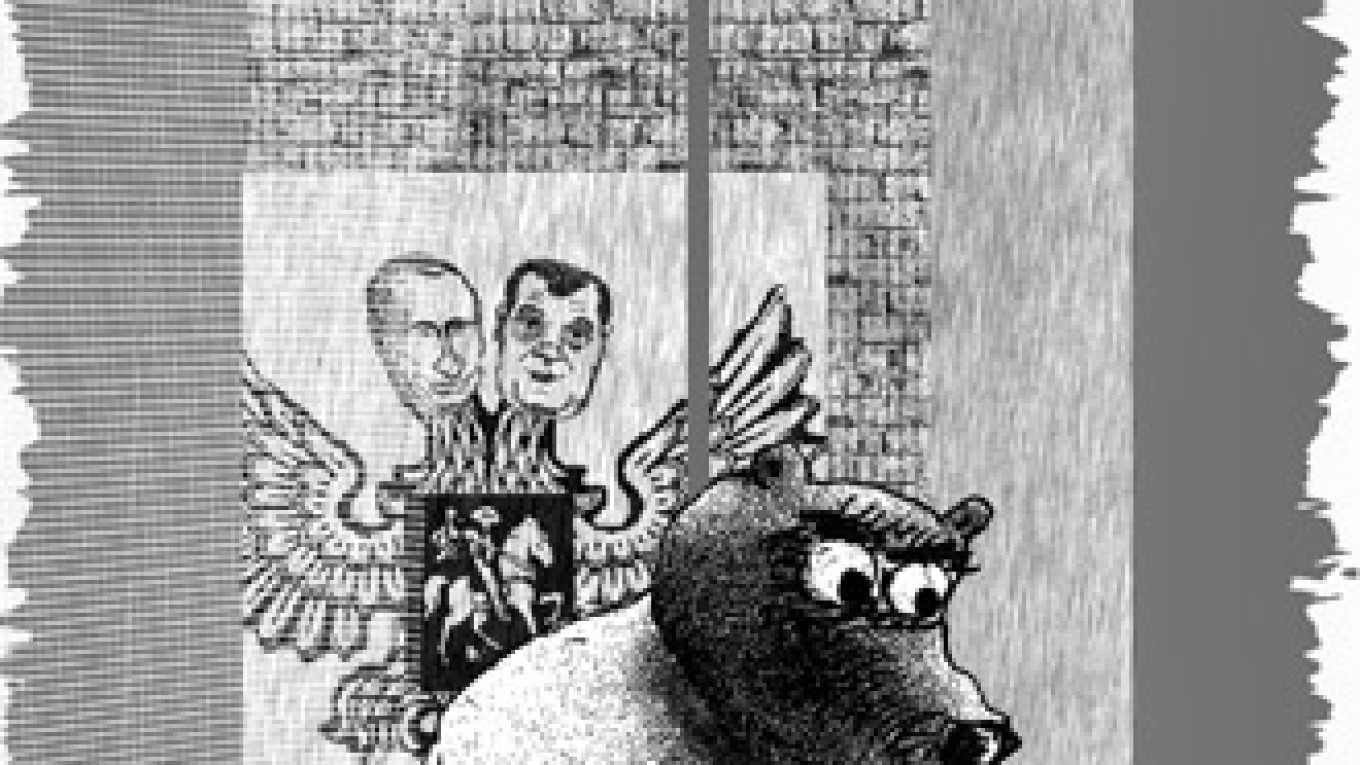

Russia’s leaders are nothing like the inflexible and single-minded Max Otto von Stirlitz, an almost James Bond-like character from the Soviet-era television miniseries “Seventeen Moments of Spring.” In fact, they are much more like Bill Murray’s tragicomic character in the movie “Groundhog Day.” Every morning they wake up in the same depressing room, drink the same vile coffee, walk out onto the same tiresome, dank street and absent-mindedly step into the same dirty puddle, filling their shoes with water. They go on to recite the same rehearsed and deeply abhorrent words to the television cameras, promising the Russian people an early and sunny spring. And the next gloomy morning, the whole thing starts all over again.

In his new article “Go Russia!” President Dmitry Medvedev acknowledges that Russia has fundamental problems that, if left unresolved, will doom it to further degradation. He describes them as being, “an inefficient economy, semi-Soviet social sphere, fragile democracy, negative demographic trends and unstable Caucasus,” along with “endemic corruption.”

But Medvedev’s patron, then-President and current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, named exactly the same problems as being the most fundamental ones facing Russia in his very first address to lawmakers in July 2000, shortly after he was elected president.

This is how Putin saw the situation almost 10 years ago:

• The demographic problem — Russia’s population was shrinking by an average of 750,000 people annually;

• Russia’s weak economy — “the growing gap between the advanced nations and Russia is pushing us into the group of Third World countries;”

• The need to build a strong democratic state that protects the freedom of its citizens, the business community, civil society and speech;

• Excessive state interference in business and corruption — “the state itself largely contributed to the dictatorship of the shadow economy and ‘gray schemes,’ rampant corruption and the massive outflow of capital;”

• Outdated and ineffective social policy — “today, a policy of general state paternalism is economically unfeasible and politically inexpedient;”

• The need to strengthen control of the central government over the regions, with the priority being a resolution of the Chechnya problem.

Subsequently, all of those problems and challenges reappeared, year after year, in each successive presidential message. Every declared reform invariably failed: judicial, land, administrative, housing, public utilities, natural monopolies and others. During the “fat 2000s,” the Russian population shrank by 4.3 million people, corruption increased by a factor of 10 and the number of state employees doubled. Efforts toward democracy have stopped, with Russia stuck fast on lists of countries that are “not free.” What’s more, the country has fallen even further behind economically. In the World Economic Forum’s index of global competitiveness, Russia dropped 12 places in 2009 to 63rd among 133 countries, behind every other member of the developing economies of Brazil, India and China. Even Turkey, Mexico and Indonesia placed higher than Russia. After a full 10 years of “getting up off our knees,” Russia remains exactly where it was — in 2001 it was No. 63 on that list, with the very same countries outpacing us. But now even more countries have passed us by, and Russia has sunk even deeper into the “Third World.” The World Economic Forum lists the same reasons for Russia’s poor economic competitiveness as it did a decade ago, putting it in 110th place for ineffective state management, 116th for the absence of legal safeguards (including judicial safeguards), 119th for the lack of protection of property rights, corruption and favoritism. What’s more, all of those problems only worsened during the past decade. Russia is having more trouble riding out the global economic crisis than other major economies, and Medvedev has acknowledged that it is the result of mistakes and omissions made in the 2000s.

Despite the fact that, overall, more money was spent on the social sphere, the situation there became qualitatively worse. Half of Russia’s working population cannot obtain access to medical services because of long waiting lists and high prices. The quality of formal education has dropped sharply, while social stratification has increased. The correlation between the size of the average pension and the average salary worsened, from 33 percent in 2000 to 22 percent in 2007. The differentiation between the standard of living and incomes among regions also increased. For the North Caucasus, 2009 has been a critical year, with the region reeling under the effects of daily attacks and terrorist acts — just as it did at the beginning of the decade. Worse, terror has become a way of life for thousands of young men and women in Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia.

Over the past decade, Russia has not achieved even one of its declared goals or recovered, even partially, from even one of its underlying illnesses. In fact, most have grown even more severe.

Now, as if starting from a clean slate, Medvedev again lists the very same problems, and promises to resolve them during the new decade that begins in four months.

Meanwhile, Putin confidentially informs Western political analysts from the Valdai discussion group that he and Medvedev will jointly decide who will become the next president in 2012. He said they will decide the question amicably because they are of “one blood.” Russia’s seemingly endless Groundhog Day continues.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.