The latest joke about the presidential election campaign in Russia comes from comic Mikhail Zadornov. "The recent electoral debates remind me of a swingers club. Everyone knows how the evening will end, but beforehand you have to introduce yourself and make small talk."

Not everyone has such erotic associations. For most people in Russia, until recently the campaign just produced a constant sense of deja vu. Voters had seen it all dozens of times before: the same frontrunner, the same "opposition" candidates who didn't look like they had a hope of victory — nor did they look like they even wanted to win. And, of course, everyone knows how the performance ends.

And then in mid-December, a new actor appeared on the stage when billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov announced that he would run for president.

This was Prokhorov's second foray into politics. Last spring, he headed the Right Cause party, only to quit a few months later after a series of scandals. At the time, it appeared that Prokhorov had left politics and gone back to his more successful hobbies, such as basketball. Few people took his bid for president seriously.

In fact, most people thought Prokhorov's presidential bid was just another Kremlin project. The skeptical view was that the Kremlin, rattled by protests, was using Prokhorov as a kind of tame opposition.

But this version stopped being plausible after Prokhorov made several bold moves. He attended the opposition rallies and even inserted their demands into his electoral platform. These included radical measures such as annulling the results of the Dec. 4 State Duma elections, introducing elections of governors and judges, limiting presidential powers and cutting the presidential term to four years. To underline the seriousness of his intentions, Prokhorov has already begun to establish a new party based on liberal political values and oriented toward the European Union as Russia's main partner in foreign relations.

Prokhorov even telephoned Soviet-era dissident Vladimir Bukovsky, whose name still makes people in the Kremlin break out in hives. After their conversation, Bukovsky wrote on the Ekho Moskvy blog: "Is Prokhorov capable of dismantling the Putin regime? I think so."

At this point, it was difficult to believe that Prokhorov was a Kremlin project.

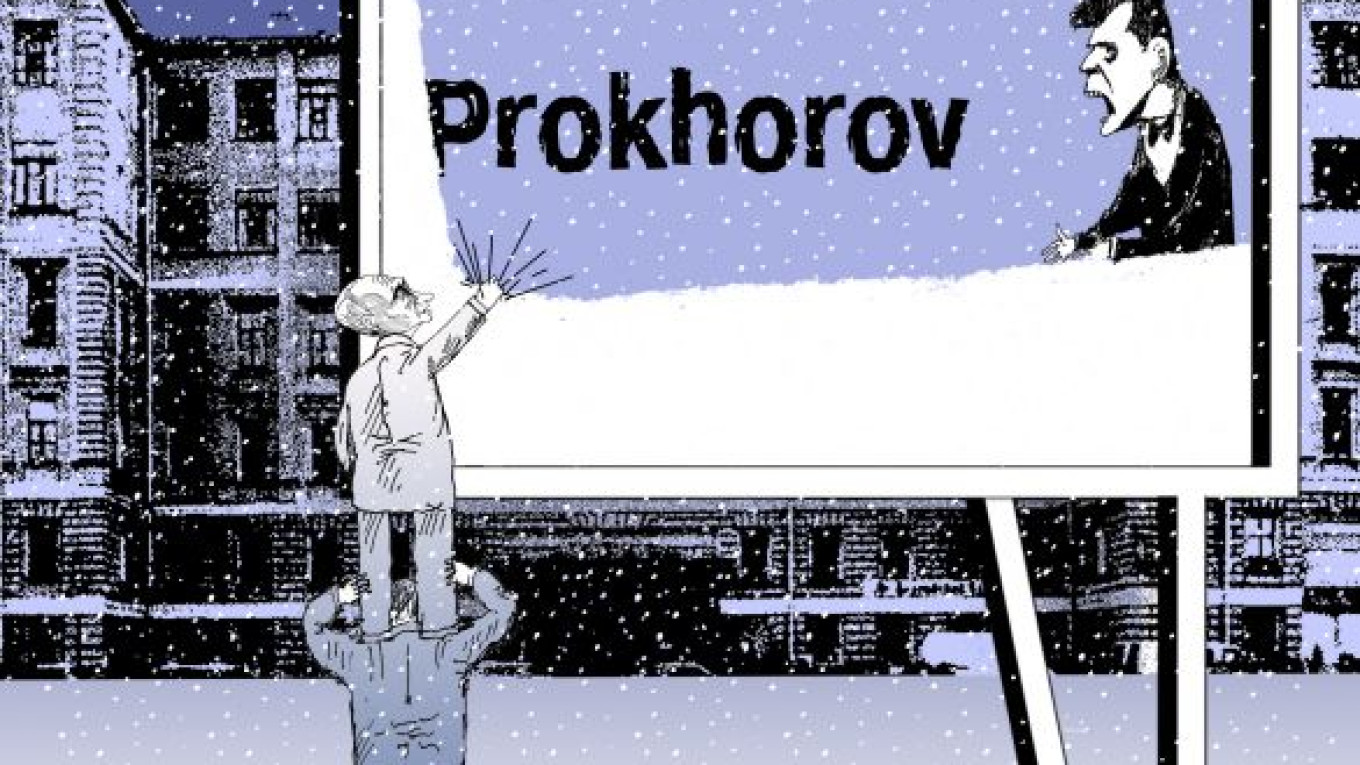

It didn't take long for the Kremlin's true attitude toward the candidate to appear. In many cities, as soon as Prokhorov's campaign billboards went up, they were torn down. In Novosibirsk, he wasn't able to meet with voters after the hall he rented was abruptly closed. And then, in the best traditions of pro-Kremlin movements, a smear campaign was initiated against him, including a mock gay calendar for the candidate from the so-called "boys of Leningrad region."

Despite these efforts, Prokhorov's rating has gone up. By the end of January, he was in second place behind Prime Minister Vladimir Putin in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The blogger Nikitskij wrote in his LiveJournal blog: "Yesterday I was in the Caffeine cafe on Sretenka. They were doing some marketing event and asking people who they were going to vote for. And they posted the results, which really surprised me: 40 percent for Prokhorov, 24 percent for Putin, 10 percent for Liberal Democratic Party leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky, 9 percent for Just Russia leader Sergei Mironov, and 7 percent for Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov. That was the vote of the 'caffeine electorate.'"

Prokhorov also has supporters among the more conservative voters. A straw vote on the site Voensud.ru for members of the armed forces gave Zyuganov a strong lead, but Prokhorov got a respectable 17 percent. But nationwide polls give Prokhorov only 6 percent to 8 percent of the vote, which rules out victory or even participation in an unlikely second round of voting.

That said, in Russia, politics don't happen at the polling stations or on the streets but rather on the rugs in Kremlin offices. The Prokhorov phenomenon shows that there is a fierce battle among the ruling elites raging on — or perhaps under — those plush rugs.

In Russian history, this kind of battle has almost always led to a regime change. Only leaders who were supremely talented diplomats and strategic thinkers — and with a strong dose of brutality to boot — were able to hold on to power.

No one who has observed Putin doubts that he is brutal enough, but it's not clear if he has everything that it takes to hold on to power.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist whose blog is .

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.