SURGUT — Wedged in between the tall cranes of a busy port and the flashy city center of western Siberia’s oil capital Surgut, lies a riverside boulevard. The walkway is freshly paved and lined with faux old-fashioned street lanterns, the frivolities of a city flushed with oil money.

Pedestrians come here for a view of the dark-grey Ob River and the expanse of typical Siberian birch forest landscape across the water. If they can look past Josef Stalin, that is.

In mid-September, a patriotic youth group made national headlines by installing a bronze bust of the Soviet dictator here, right at the very center of the promenade. Several weeks later, after much protest, the local authorities took it down declaring it lacked the required permit.

The activists are furious and have filed a complaint for "theft." The battle over the bust, they told The Moscow Times, "will continue." So far, it has been a bloody one. Twice, the bust was attacked with red paint.

“Now Stalin doesn’t only have blood on his hands, but also on his face,” said Pavel Akimov several days before the dismantling, with barely disguised glee. His muttered condemnation of the “vandals” who did it was not altogether convincing.

As the son of farmers who were forcibly deported to Surgut in Soviet times, 71-year-old Akimov would consider any bust to Stalin anywhere a personal affront. This one was particularly offensive, however, placed as it was roughly 25 meters away from the site of a future memorial to the victims of repression under Stalin, which he has helped organize.

Staring straight at his victims, Surgut’s Stalin was a rare physical manifestation of a deep rift in Russian society over his legacy that is unlikely to disappear with the removal of the bust. On Putin's watch, support for Stalin has grown to a point where it is now threatening to run out of the authorities' own control.

A Long Winter

Like many other residents of Surgut, Akimov’s life has been deeply influenced by Stalin.

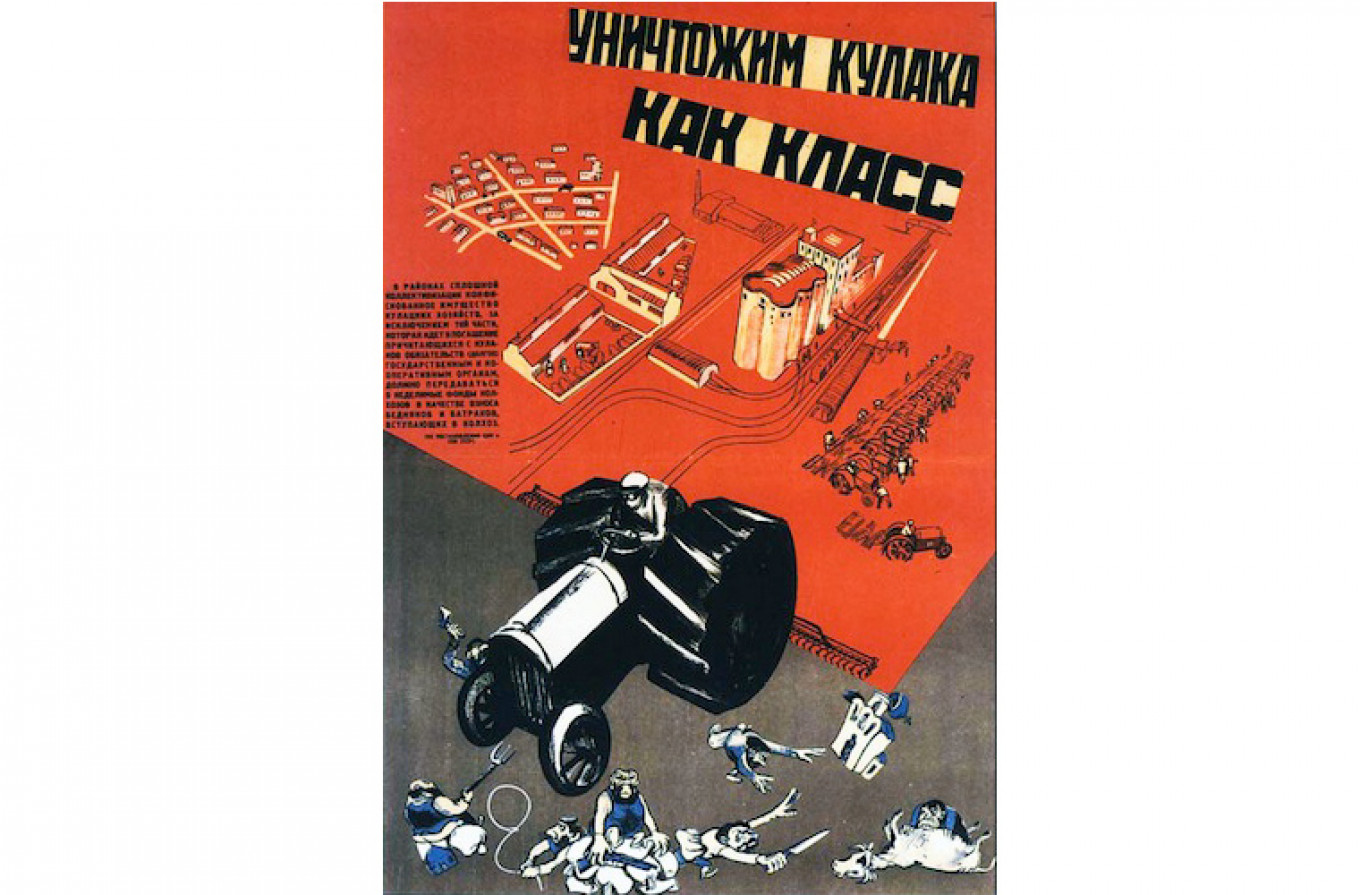

Both his parents came from families of kulaks, so-called wealthy Russian farmers, in the Tyumen region. Their ownership of nine horses, several cows and some tools was, says Akimov, enough to put them on the wrong side of the Bolshevik leadership.

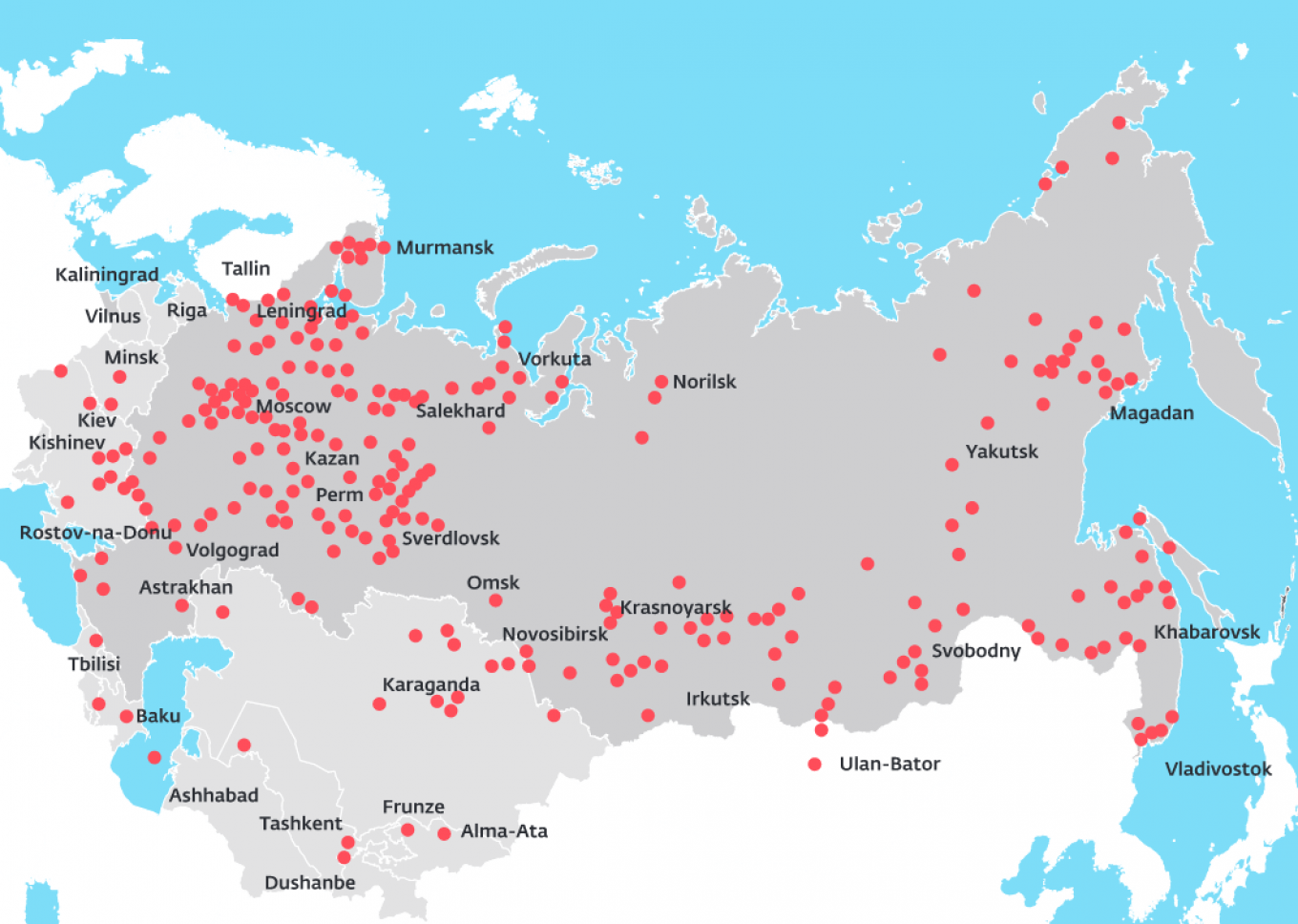

In the autumn of 1930, Akimov’s parents and tens of thousands of other farmers were forcibly relocated northwards, through Tobolsk to Surgut. Conditions en route were harsh, and many did not survive the journey. “They threw the bodies out onto the snow or into the river,” says Akimov. Those fortunate enough to make it to their destination in the subarctic taiga were left to survive in whatever way they could.

Around 150,000 people crossed Tobolsk toward Surgut in the late twenties and early thirties. According to Akimov, only one third of that number was still alive in 1933.

In Surgut, displaced kulaks formed as much as a third of the city’s population, he says. They worked in logging or at a nearby fish processing plant, which once stood where the memorial is now set to be built.

Just as they were getting settled, however, the Soviet regime stepped up its crackdown on the kulaks, this time with the intention of “liquidating it as a class.” According to Akimov, 134 farmers were rounded up and executed in Surgut alone. “They shot the elderly and the young — 17 -year-olds — who were somehow guilty in the eyes of the Soviet authorities,” he says.

His research, which has brought him “many sleepless nights,” left him in little doubt that Stalin’s hands were soaked in blood. “When decisions were made, Stalin was the person who signed off on the plans,” says Akimov. “Without his consent, nothing happened.”

Today, around 750 direct descendants of the kulaks remain in the city of Surgut, most of them pensioners. To make sure their memories live on for a new generation, the “Our Memory” group that Akimov leads was given permission to build a large monument on Surgut’s river front. It will consist of two stone slabs, nine meters tall, with a bronze figure emerging from the middle to represent those who managed to survive.

If left up to local activists, however, the bronze survivor would walk straight into the line of sight of its slaughterer, much to Akimov's horror.

“No matter where you turn, in this region there are descendants of those who were forcibly exiled here or shot,” he says. “There is no place for Stalin here. This bust is pure sacrilege.”

A Bust to Victory

Those behind the Stalin bust disagree.

The “Working Youth of Siberia,” an umbrella organization for more than a dozen “patriotically minded groups,” first thought of the idea during last May’s Victory Day. The event marked the 70th anniversary of Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany, and the group had hung up posters of Stalin around the city, only to have them taken down by local authorities.

First, the group played by the rules and submitted a request for an official permit in late May. But when they received no answer, they decided to go ahead anyway.

“Stalin was a wise leader. He made Russia into an industrial force and gave development a huge push: we went into space, developed nuclear weapons and power stations,” says Denis Khanzhin, a 28-year-old with a round, childlike face. “But his main achievement was establishing order.”

For these young Russians, most of whom are in their late twenties, “order” is high on their priorities list. They advocate a lifestyle with no crime or substance abuse — they don't smoke or drink — and are nostalgic for a time when the rules were clear and the government dependable.

“Of course now we have President Putin,” says fellow activist Albert Bulatov. “We wish that development was faster. But today there are many rules and obstacles, back in the day things were simpler.” He sounds nostalgic.

The activists say Stalin’s reputation has been undermined by “myths” and “lies.” “The numbers are so exaggerated! We need to see the past the way it was, or else we have no future,” says Bulatov.

Another activist suggests “no one who lived fairly was targeted,” and that those displaced or executed under Stalin included “murderers.”

The group claims to have popular backing and accuses the local authorities of unfairly choosing sides in the debate over Stalin’s legacy. “It’s fine to have a monument, but it should be a monument to the innocent victims of complicated times,” says Bulatov. The others nod.

Memory Blank

According to Akimov, of “Our Memory,” Stalin’s revival has been fueled by ignorance over the details of his repressive policies. “Youngsters are being told matter-of-factly: there was repression,” he says. “They have no idea what it means or its scope.”

But it would be wrong to dismiss the Surgut youth activists as illiterate. Most of them are well-off and work as engineers for the local branches of gas giant Gazprom or Surgutneftegaz. As they talk, they throw around enough facts to show an understanding of history.

More important is the emotional and political appeal of Stalin, says historian Nikolai Svanidze. “It is being approached as a political, not a historical question,” he says.

According to Svanidze, Stalin has become a symbolic counterweight to the lawlessness many Russians feel existed in the 90s and continues to this day. “Stalin has become a symbol for order, honesty, harsh justice,” he says. “The more difficult life will get, the more ‘protest’ will manifest itself in support for Stalin, causing deep division in society.”

Polls show support for Stalin has risen in recent years, with almost half the population judging his leadership as having had benefits.

Svanidze, the historian, predicts more statues of Stalin and controversy in the near future, with ordinary Russians battling against each other for their own version of the truth.

The Kremlin, meanwhile, is doing little to provide a unified narrative. While President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev have publicly condemned Stalin, the Kremlin-led wave of patriotic rhetoric and glorifying of the Soviet role in WWII sends a more ambiguous message.

Earlier this year, the Kremlin also appointed a new education minister, Olga Vasilyeva, a religious scholar and historian who some have accused of being too soft on Stalin’s role. Russia’s only preserved labor camp which also served as a museum, Perm-36, was forced to close after increasing government pressure. And the country’s most prominent NGO to remember the victims of repression, Memorial, has been labeled a “foreign agent."

The Surgut group says they have been contacted by fellow activists from all over the country asking for the details of the sculptor who made the bust (a man in North Ossetia.)

In Kazan, local activist Ravil Garifullin is 3-D printing his bust of “Generalissimo Stalin,” to be put up in the city center once the municipal authorities give their go-ahead. He expects it to go up within the next six months, he told The Moscow Times.

Meanwhile, in Novosibirsk, a city which suffered heavily during the war, a group of residents is trying to fight plans to unveil a bust to Stalin put forward by the local Communist Party.

“The communists have been conducting their ‘ritual dances’ around the figure of Stalin, expecting to draw in patriotically-oriented voters,” says Novosibirsk activist Dmitry Kholyavchenko. “It’s astonishing that Stalin’s legacy has been made an open question again, denying obvious historical facts and elementary human values.” So far, Kholyavchenko’s petition against the bust has gathered 766 signatures, in a city of more than a million residents.

Back in Surgut, the saga around the bust to Stalin promises to drag on. The Surgut youth group shows no sign of relenting and hint a bust of the feared Soviet secret police chief Lavrenty Beria, could be next.

“Imagine what my father would say if he were still around?” Akimov asks.

On the boulevard, before the bust was taken down, most pedestrians seemed immune to the controversy. Young and old stopped by the statue for photos. “Stalin is part of our history!” a man in his seventies walking along the promenade says. “We’re not razing churches to the ground just because of the Inquisition, are we?”

As a watery sun rose up high in the sky, it caught a golden engraving on the bust’s pedestal citing words reportedly uttered by Stalin to Molotov before his death in 1953.

“I know that after my death a pile of rubbish will be heaped on my grave, but the wind of history will sooner or later sweep it away without mercy” — the inscription reads.

In Surgut, as in much of Russia, that wind appears to be picking up.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.