Alexei Navalny has spent years publishing revelations of the ill-gotten luxuries of Russia's elite and seeing them ignored by authorities. But when the blogger and opposition politician's anti-corruption fund unveiled an investigation linking colleagues of Russian Prosecutor General Yury Chaika to the bloodiest bandits of recent years, Navalny thought they would be forced to act.

Published on Dec. 1, the investigation linked Chaika's deputy, Gennady Lopatin, and another prosecutor, Alexei Staroverov, to the leaders of the Tsapok gang, who terrorized the town of Kushchevskaya in southern Russia through systematic rape and theft for more than a decade before their slaughtering of 12 people, including four children, forced authorities to intervene in 2010.

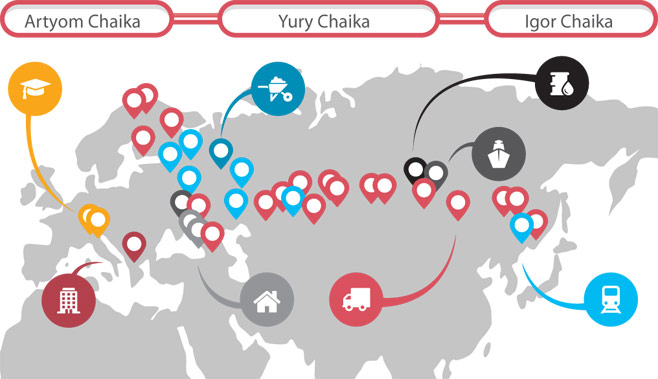

It also linked Chaika's son, Artyom, to the expropriation of a shipping company in the Far East whose director was allegedly strangled, and documented the apparent rigging of auctions for lucrative state contracts by Artyom's brother, Igor. The investigation showed how both Chaika's sons, who have amassed businesses and real estate worth millions of dollars, enjoyed the protection of prosecutors.

It took the public by storm. Three million people watched a Russian-language film version of the investigation on YouTube in less than a week. But there were no mass firings or public investigation opened. Yury Chaika branded it an attempt to discredit him, while Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said it was not interested in the dealings of Chaika's "grown-up" sons, whose affairs he said had nothing to do with the Prosecutor General.

Two days after the investigation was published, President Vladimir Putin made his traditional denouncement of corruption during his annual state of the nation address. Chaika watched calmly from the front of the audience as Putin asked the Prosecutor's Office to be vigilant.

The reaction is a familiar one in Russia, where almost every member of elite that emerged from the 1990s had dealings with organized crime. News that officials are corrupt surprised few — particularly in the Kremlin.

Chaika's web of shadowy connections.

Moreover, Putin has made it a point never to react to outside pressure or cut loose members of his cabal. "Putin's mind is set: if he reacts [and fires Chaika] that makes him vulnerable — not in front of society, but in front of his siloviki," a source close to the security services told The Moscow Times, using a word that refers to "strongmen" officials with roots in law enforcement.

But the investigation did ruffle feathers in the Kremlin, according to two sources close to the security services. Even in Russia, associating with gangsters like the Tsapoks is a step too far, one source said. Also damaging are the connections amassed by Artyom Chaika in Switzerland, where Navalny's investigation revealed he bought several houses and a residence permit. Putin and his inner circle would see this as treason — particularly dangerous if it exposes insiders with sensitive information to foreign pressure at a time when the Kremlin's relations with the West have soured over Ukraine, the sources said.

By Russian standards, the reaction to the investigation was big. The Kremlin, which ignores Navalny to the extent that it refuses to utter his name, felt forced to comment. Navalny's targets rarely respond to his findings, yet Chaika defended himself. Soon after the investigation came out, independent television channel Dozhd, which had helped Navalny gather evidence, was raided by prosecutors in what one source called a "knee-jerk" reaction to the scandal.

Navalny told The Moscow Times he was surprised that so few people argued with or tried to smear his conclusions, and by the small number of people who publicly defended Chaika.

But that does not mean that things will change. State-run television is not giving airtime to the case, and headlines fade. "We're realistic people," Navalny said, and we know they won't fire anyone — "it would contradict the very basis of the regime."

In a blog post following the publication, Navalny said the burden was now on the public to spread the word and journalists to "obtain a reasonable reaction and reasonable answers."

This will prove difficult. "Unlike American media, Russian media aren't used to catching their prey," Navalny told The Moscow Times.

But Putin may do the job for them. Chaika could suffer the fate of his predecessor in the Prosecutor General's Office, Vladimir Ustinov, who was abruptly fired at Putin's request in 2006. No explanation for the sacking was ever given.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.