At the height of the recent 70th anniversary celebrations of Victory Day, I recalled another 70th anniversary that matched these for hype and bluster — right down to the posters on every street corner, the slogans, the concerts by Soviet crooners Lev Leshchenko and Iosif Kobzon, the solemn meetings and the foreign guests from Asia, Africa and the friendly part of Europe.

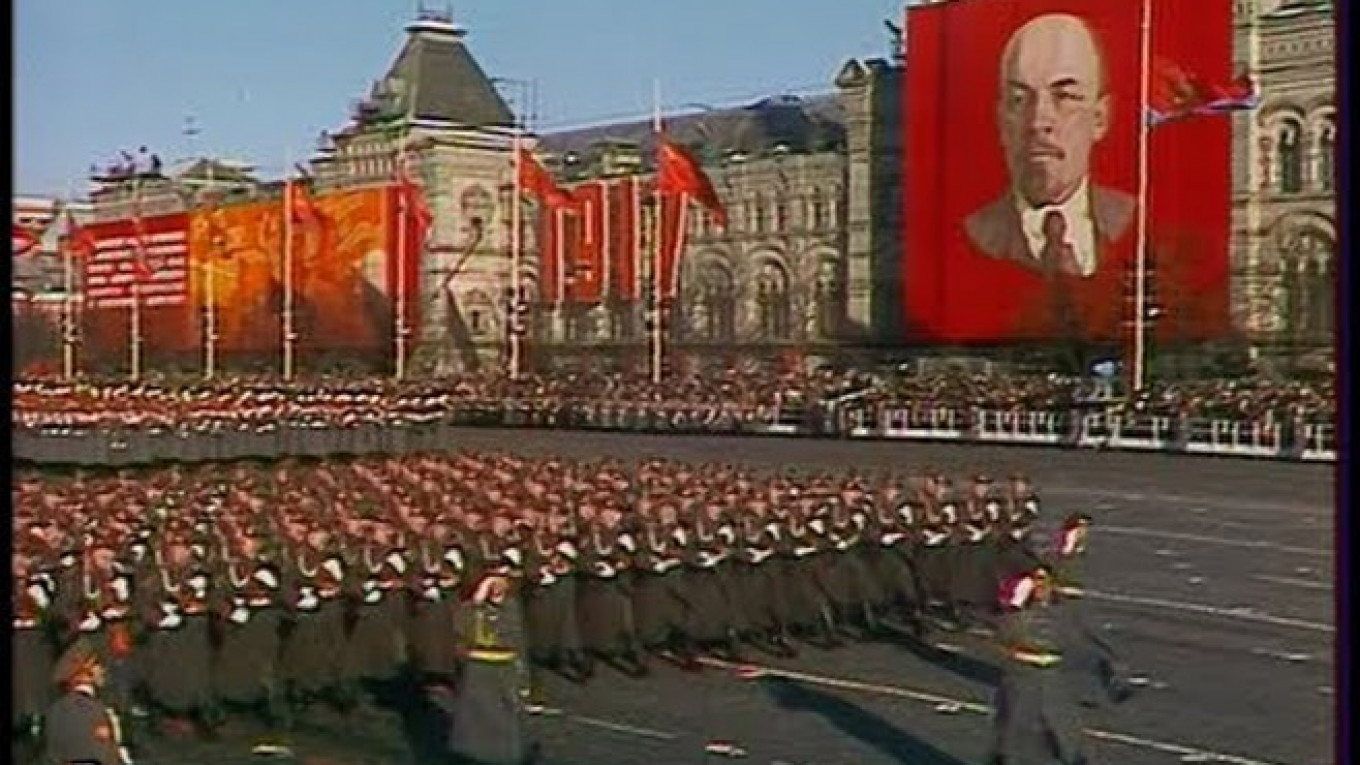

Many today have forgotten, but the Soviet Union celebrated the 70th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1987 on a similar scale and in nearly identical style to this year's Victory Day celebrations. The only difference was that the ribbons were red, there were more buttons and badges bearing Lenin's likeness and there were incomparably fewer private cars — and fewer themed stickers to plaster on them for the holiday.

Back in 1987, Soviet leaders had no thought of dismantling the country. On the contrary, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced perestroika as a means for renewing and strengthening the Soviet Union and for accelerating economic development. Few outside observers had any reason to doubt that those plans would succeed.

Now, only nostalgic left-wingers celebrate anniversaries of the Bolshevik Revolution, and the pathos that marked that holiday in 1987 looks artificial and tragicomic considering how the grand attempt to build a socialist society ended for both the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

But standing before Lenin's mausoleum back in November of 1987, Gorbachev, former Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu and former East German leader Erich Honecker did not know what awaited them in the very near future. Few doubted that the country would eventually celebrate the 100th anniversary, an event that Soviet citizens had patiently prepared for by placing messages in time capsules to be opened by future generations.

However, just four years later nothing was left of all that had seemed enduring and constant: the Communist Party was outlawed, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics lived out its last dying days and East Germany had ceased to exist. As for Ceausescu, he was executed by his fellow citizens even earlier — in December 1989.

Paradoxically, the current Victory Day celebrations are rooted in those half-forgotten times. Back in 1987, the authorities also talked a lot about the Great Victory, as well as the recently launched perestroika. For millions of Soviet citizens, the events during and surrounding World War II were closer and more personal than legends of the revolution 70 years earlier.

Over the years of Soviet rule, the myth surrounding the revolution had gone through countless permutations until, by 1987, it had finally become nothing more than a set of standard catchphrases and official pronouncements.

In order to somehow revive the moribund holiday, government officials tried to infuse it with new meaning and significance. We are witnessing a similar process now: the authorities are attempting by hook or by crook to tie the anniversary of the Great Victory in 1945 to the current political agenda.

Worst of all, they are inculcating a connection between patriotism for Russia and contempt for this country's former allies in the war against Hitler, as well as support for the conflict against Ukraine.

Seven decades separate 2015 from the war victory of 1945, just as 70 years separated 1987 from the October Revolution of 1917.

And despite the differences between the two anniversaries, they share some basic features — a paucity of surviving eyewitnesses and an ever-increasing pomposity by officials who use them for public relations purposes and to gain added legitimacy with the help of a commemorative ribbon on their chest.

Fyodor Krasheninnikov is the president of the Institute for Development and Modernization of Public Relations in Yekaterinburg. This comment originally appeared in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.