In the run-up to Victory Day on May 9, when Russia commemorates 70 years since the Allied victory over Nazi Germany, staff members at The Moscow Times describe the wartime experiences of their own families.

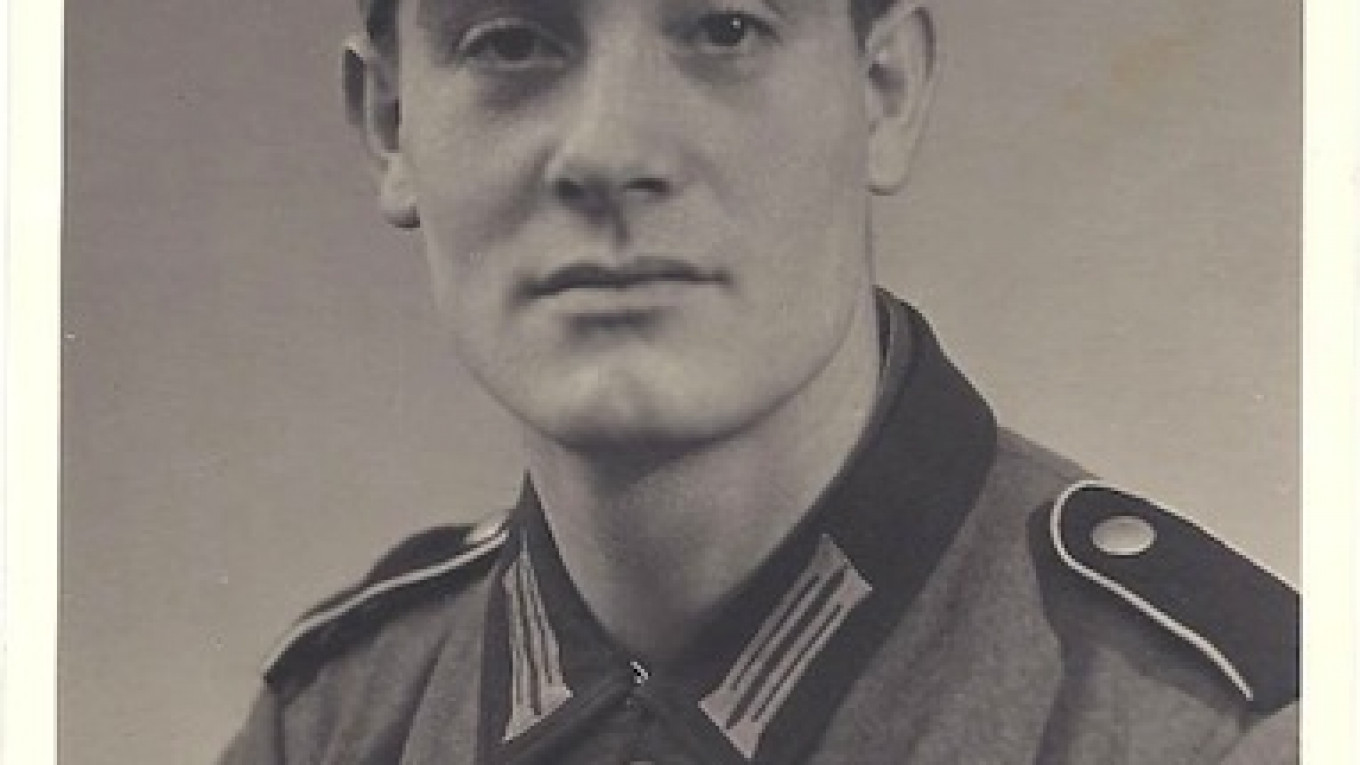

Today, social media editor Katrin Scheib tells the story of her grandfather.

When my grandfather, Guenter Scheib, was called to a political protest march that had turned violent in 1933, it wasn't an unusual thing to happen. A Communist and member of the workers' movement, he was also a paramedic.

Even back then, National Socialism was strong in Hilden, his hometown near Düsseldorf in Germany's Rhineland. Five years later, during the Night of Broken Glass, it would be the town with the largest number of deaths compared to its population.

But this was still 1933, and my grandfather was one of the well-known local ''Reds.'' As he arrived to treat the injured, a group of SA men surrounded him and held a gun to his stomach. They fired once and left him behind, saying ''Leave the pig alone, that one's had enough.'' The bullet got lodged in his kidney, and he was saved by a surgeon at Hilden hospital.

Communist or not, being German meant he had to fight in Hitler's war. Ranking as a Stabsgefreiter (Corporal) he was in Belgium first, then moved on to France and onwards to the Channel Islands. From 1940, he was part of the occupying forces on Jersey and Guernsey, working as a medic again. Compared to his earlier wartime experiences, it must have been a quiet life: After the war, Opa Guenter would describe it as ''that time when we were guarding the tomatoes on Guernsey.''

When Germany surrendered at last, he became a British PoW, first in Sheffield, then in Devizes. During the regular medical checks at the camp, a German doctor hinted to the prisoners that they needed to complain more if they wanted to be sent home. So my grandfather pretended the scar from being shot in 1933 was a war injury and had somebody teach him a few words in English so he could claim to be in ''much pain, much pain.''

My grandparents had decided not to have children as long as there was a risk of ''producing cannon fodder for Hitler.'' We don't know the exact date my grandfather was let go, but we do know that the wound inflicted by the Nazis in 1933 helped to speed up his release, and that he arrived back in Hilden in early 1946.

My father was born in January 1947.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.