On March 7, two men were arrested for their alleged involvement in the murder of Boris Nemtsov, then three more. All five come from the North Caucasus, at least two are Chechens. Now there's a surprise.

It is a pretty safe bet that there will be a disproportionate North Caucasus inflection to the media coverage of the investigation. You'll see the pattern from high-profile cases such as the murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 2006 to the daily Moscow crime blotter.

On one level, this smacks of a tendency to "round up the usual suspects." Ever since the 19th century the people of the Caucasus have been among the Russians' favorite folk devils, especially the Chechens, "a bold and dangerous people" in the words of Alexei Yermolov, tsarist viceroy of the Caucasus.

Chechen, Georgian and Azeri organized crime has been elevated to the status of national threat, even though the majority of Russia's gangsters — if not those professing the anachronistic title of vor v zakone, "thief within the code" — are Slavs. Indeed, the head of Moscow's criminal investigations division flatly said that "Most crimes [in the city] are perpetrated by relatively small gangs of illegal migrants."

That people from the Caucasus are being blamed for Nemtsov's murder — at least for being the people who executed it, whoever may be behind them — can thus look like a predictable piece of political theater.

It helps distract attention from the violent ultranationalists who undoubtedly considered Nemtsov a traitor. With Putin being close to the nationalist Night Wolves motorcycle gang (he even gave their chieftain, Alexander "The Surgeon" Zaldostanov a medal in 2013), this might have been an embarrassment.

Add the role of these "ultras" in providing volunteers for the war in eastern Ukraine, and it may be understandable why the government would want to avoid disputes with the thuggish right.

On the other hand, the unfortunate truth is that while not the dominant underworld force the Russian popular press — and Interior Ministry spokespeople — portray them as being, people from the Caucasus do genuinely play a disproportionate role in violent crime in general, contract killing in particular.

In part, this represents their reputation as violent, tough and ruthless. To an extent, this is mythologized, but not completely so, something even Caucasian community leaders will accept. One once proudly told me that "our boys are fearless. They enjoy a fight, and fight to win."

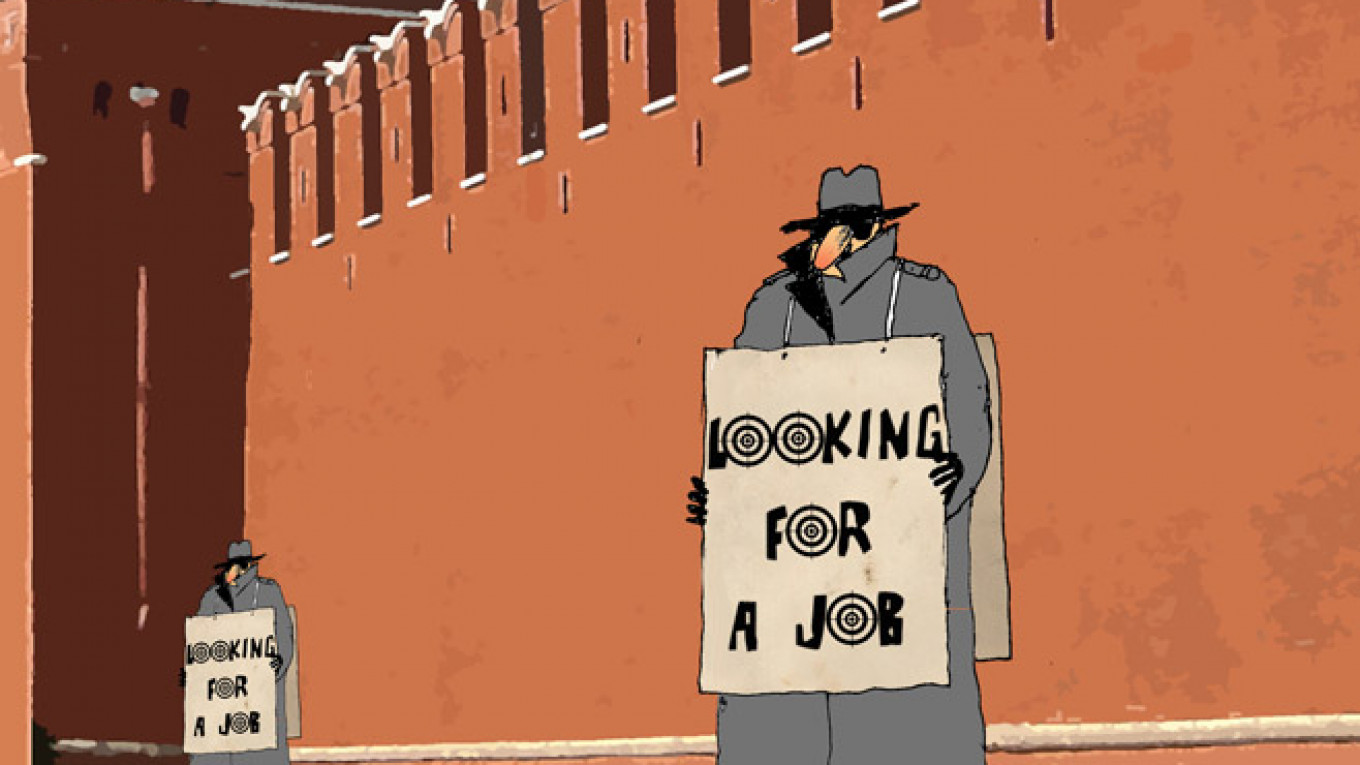

It does mean they have something of a "brand name." Some years back, a former (or so he assured me) gangster told me that in his network "a job for a Chechen" had become a common euphemism for a killing. Often, those wanting such hit men explicitly seek to hire people from the Caucasus in a vicious circle of supply and demand.

More generally, the two wars in Chechnya and the lower-key but still brutal campaign of terrorism and counter-terrorism in the rest of the North Caucasus have created a pool of potential killers. Their experiences have given them the necessary skills, and stripped them of the alternative opportunities or simply the moral restraints to prevent them becoming involved in this "business."

After all, we have seen Chechens and others from the Caucasus providing the muscle behind all kinds of causes and ventures. As well as their own criminal organizations, they have been the "torpedoes" — contract killers — for many others. They have even been used by Russian nationalists in their feuds.

In Chechnya, many of the most vicious skirmishes took place between Chechen rebels and Chechen government fighters, the so-called "Kadyrovtsy." And when last year the GRU, military intelligence, wanted to remind the unruly rebels of Donetsk that they fought at Moscow's pleasure, they used the Vostok Battalion. Named for a disbanded unit of Chechen ex-guerrillas, it was initially largely manned by Chechens and other fighters from the Caucasus, before they were replaced by Ukrainian volunteers.

Barring conclusive evidence to the contrary, the quick arrest of some Caucasians will do little to convince those already skeptical of the Kremlin that they were indeed Nemtsov's killers. It looks a lot like a lazy reach for a convenient scapegoat.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that one alleged assassin, Zaur Dadayev, spent a decade as one of those "Kadyrovtsy." He could have been moonlighting as a hit man — that is sadly not uncommon — but it also raises the prospect that Chechen warlord-president Ramzan Kadyrov might have had a hand in the killing.

Kadyrov — whom some also said had a hand in Politkovskaya's murder — makes much of his loyalty to Putin. However, he is also willful, aggressive and prone to act on his own impulses.

If he was at all responsible, and if he did so without any encouragement from the Kremlin, then it raises further questions about just how far Putin is really in charge of Chechnya. It brings a whole new meaning to the idea of "a job for a Chechen."

Mark Galeotti is professor of global affairs at New York University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.