When Sergei Shoigu took the reins of the Defense Ministry on Thursday, he officially inherited a military at a crossroads, torn between tradition and the half-completed reforms of his disgraced predecessor, Anatoly Serdyukov.

Shoigu will have to decide between maintaining a large, conventional force or pursuing Serdyukov’s goal of creating a leaner, more modern military, analysts said.

While servicemen rejoiced at the ouster of Russia’s arguably least popular minister, analysts suggested that it was still too early to say which path Shoigu would follow.

Although the day saw more speculation than action, the news that Shoigu had appointed longtime aide Yury Sadovenko to head the ministry’s administration suggested that a transition was already under way behind the scenes.

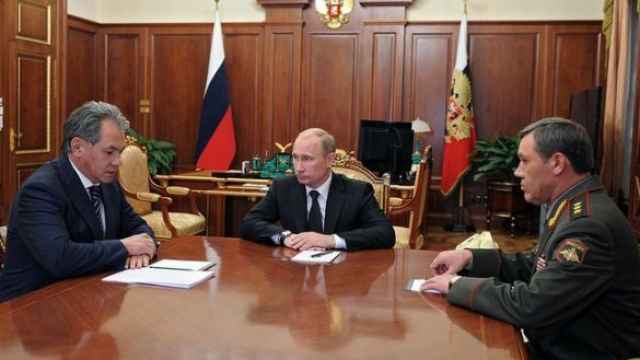

That sense was enhanced by news reports that cited undisclosed military sources as saying Shoigu would name Major General Valery Gerasimov, a reputed conservative, to replace the reformist General Staff chief Nikolai Makarov.

Analysts interviewed by The Moscow Times said Shoigu faces many challenges, as years of underinvestment have left the military with outdated weapons, and poor management and corruption have eaten away at the force’s battle-worthiness.

The current force is able to fight short, relatively small-scale skirmishes, like the brief August 2008 conflict with Georgia, but not a prolonged war, said Alexander Khramchikhin, deputy director of the Institute for Political and Military Analysis.

Also, Serdyukov’s modernizing reforms have stalled, leaving the military in limbo between its past as a large conscription force and its future, most likely as a professional one.

“Clearly, there is a sort of tension between the need to be a great, large force versus a modern, technologically equipped force that is capable of dealing with current security issues,” James Nixey, an analyst with Chatham House, said by telephone Thursday.

For example, Russia is one of the few G20 countries with a conscription army, though reforms under Serdyukov reduced obligatory service from two years to one.

Analysts were cautious about what to expect from Shoigu, the first defense minister in more than a decade to hold the rank of general. Shoigu served as Emergency Situations Minister from 1994 until earlier this year, when he was appointed governor of the Moscow region.

“Shoigu comes with a reputation as a strong administrator, but his position on reform is less clear,” said Nicholas de Larrinaga, Europe editor at Jane’s Defence Weekly, in an e-mail message on Thursday.

Khramchikhin predicted that Shoigu would use “trial and error” because he doesn’t have a military philosophy by which to act.

Given that Shoigu is fiercely loyal to President Vladimir Putin, who has often bemoaned the loss of the Soviet Union’s “great power” status, Shoigu might look to build a large, Soviet-style military, said Chatham House’s Nixey.

But De Larrinaga said Shoigu’s ties to Putin might have precisely the opposite effect, causing him to press ahead with reforms under Serdyukov, a Putin appointee.

“Immediately, however, it is likely that Shoigu will continue where Serdyukov left off on reform as Putin has considerable political capital invested in improving the state of the military,” De Larrinaga said.

Shoigu is expected to fire General Staff chief Makarov, a Serdyukov ally, and his choice of replacement could be a good indication of his plans, De Larrinaga said.

News reports that Shoigu would appoint Gerasimov, who opposed Serdyukov’s reforms, could indicate that Shoigu would try to undo at least part of his predecessor’s legacy.

But in some areas, such as weapons purchases, Shoigu might come against the reality of dealing with a defense industry that has failed to keep up with the West.

“Much of [the military’s] equipment stocks remain aged and out of date, while the country’s defense industry is inefficient, has suffered from a lack of investment in many sectors, and is incapable of matching the technologies produced in the West,” De Larrinaga said.

Serdyukov caught flak from Russia’s powerful defense industry for proposing that the military buy more foreign-made weapons, including French-built Mistral amphibious assault ships and German tanks.

“Just like Serdyukov, Shoigu is not going to buy old equipment,” said Igor Korotchenko, head of the Defense Ministry’s public advisory council.

Instead, Shoigu will continue the practice of buying limited amounts of foreign equipment for experimentation and to spur domestic manufacturers, Korotchenko said by telephone.

Putin said during his presidential campaign in February that Russia’s armed forces would receive over 400 ballistic missiles, eight submarines and more than 2,300 tanks over the next decade.

Serdyukov, who became defense minister in 2007, was responsible for carrying out major reforms that transformed the Soviet-era military into a more modern force.

He also reduced the size of the army considerably, making painful cuts to ranks of middle officers and generals, and simplifying a tangled bureaucracy.

Dramatic increases to the military’s budget in recent years helped provide troops with new weapons and tools, raise salaries and improve housing.

“In many ways the reforms Serdyukov launched, particularly the massive recapitalization of Russia’s military equipment, are still in their infancy,” De Larrinaga said.

But nevertheless, he was widely loathed among active servicemen, who regarded him as a hostile outsider hellbent on outsourcing and gutting the system. Soldiers and officers mocked his background in the furniture business and as a tax official.

Serdyukov also failed to end vicious, institutionalized hazing of new conscripts, and the military has been embarrassed by a string of deadly fires at weapons depots.

“Nobody I asked doubted for a second that removing Serdyukov was the correct and sound decision — 100 percent of respondents,” Grigory Prutyan, an active-duty military doctor, said Wednesday on his blog on Ekho Moskvy’s website.

Nixey, of Chatham House, suggested that criticism from within the military needed to be taken with a grain of salt.

“If you are in the military, the chances are that you would not have done very well under a Serdyukov’s regime,” he said, adding that it was noteworthy, given staunch opposition within the military, that Serdyukov lasted on the job for almost six years.

And although it was a corruption scandal that eventually ousted Serdyukov, he wasn’t known for being any more corrupt than other ministers, Nixey said.

Last month, investigators opened five criminal cases in connection with allegedly illegal sales of military property, including sanatoriums, guest houses and land worth $95.5 million, by the Oboronservis firm, which was chaired by Serdyukov until last year.

Also on Wednesday, police detained a businessman on suspicion of soliciting a 3 million ruble bribe to “speed up” a deal for the sale of Oboronservis property in the Moscow region.

Investigative Committee spokesman Vladimir Markin said Wednesday that more arrests in the case were to come.

Putin indicated Tuesday that the embezzlement scandal around Oboronservis was the main reason for Serdyukov’s dismissal from his post, though pundits say conflicts with Putin allies and other law enforcement officials played a role as well.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.