President Vladimir Putin must have smiled when he saw the results of a VTsIOM poll taken on July 15, in which 64 percent of respondents said they opposed foreign-funded nongovernmental organizations that are "politically active" in Russia. All of his hard work on the anti-Western propaganda front over the years seems to have paid off.

Granted, Putin got a little help from VTsIOM itself, which explained to the respondents before they voted, most of whom have little knowledge of what these organizations really do, that many foreign-funded NGOs organize protests and rallies — a clear distortion of the facts.

Nonetheless, Putin can congratulate himself on a propaganda job well done. Using his heavy administrative resources, Putin strengthened Russians' convictions that foreign-funded NGOs play a negative, if not subversive, role in Russian society — that they are inherently "anti-Russian," interfere in Russia's internal affairs and are part of a larger, soft-power U.S. secret project to execute an Orange Revolution in the country.

Putin began his attack on NGOs in earnest in December 2005, when, as president, he signed a law that placed exorbitant registration requirements on these organizations and required foreign-funded NGOs, in particular, to reregister all over again. Then, during his 2007 Luzhniki speech, Putin accused unspecified NGOs of being "jackals" for accepting grants from foreign governments.

This smear campaign intensified in December after the Golos elections watchdog produced evidence that as much as 20 percent of the State Duma election votes were outright falsified or otherwise manipulated to boost United Russia's results.

State-controlled NTV made a significant contribution to the NGO vilification campaign by broadcasting several pseudo-investigative programs from December to March, including, "The West Will Help Them," which claimed that Golos, on U.S. orders, disseminates false information about electoral fraud to discredit Russia.

In addition, NTV aired "Anatomy of a Protest," which showed how opposition protesters were supposedly paid to attend rallies. The program also implied that U.S. diplomats, who were "caught on tape" attending protest rallies, were somehow orchestrating the events.

It was also NTV that released an Internet video in mid-January titled "Receiving Instructions From the New Ambassador," in which NTV journalists bombarded opposition leaders and directors of foreign-funded NGOs with questions as they approached the U.S. Embassy for a meeting with the new ambassador. Questions included, "Why are you going to the U.S. Embassy?" and "What is your goal?"

Amid all this disinformation and state propaganda against foreign-funded NGOs, a crucial principle is lost on many Russians: By helping victims of human rights abuses and exposing government corruption and other abuses of power, these NGOs serve the Russian people much more than they do foreign interests.

The July VTsIOM poll also showed that 73 percent of the respondents agreed that financial audits needed to be strengthened for foreign-funded NGOs, a key element of the new NGO law. This reflects, in part, a common belief among Russians that there is a high level of corruption among foreign-funded NGOs.

In reality, however, the audit procedures for NGOs receiving foreign grants have traditionally been strict. The United States, for example, requires Russian-based NGOs that receive U.S. government grants to submit yearly independent audits, and virtually every dollar spent from the grant must be justified, including money spent on pens and pencils and on coffee breaks at seminars. Grants have been terminated for NGOs that cannot justify their expenses.

There are, indeed, corrupt NGOs operating in Russia, but it would appear that the majority of them are Russian-funded. A vivid example is the Federation Fund, a charity that was run by a Kremlin insider and supposed to have helped cancer-stricken children. In August 2011, the fund was hit with embarrassing claims that money raised at an event attended by Hollywood stars like Sharon Stone and Mickey Rourke — as well as Putin, who sang "Blueberry Hill" to guests — went unaccounted for. It is no surprise that this scandal and others like it involving Russia-funded NGOs have seriously undermined Russians' faith in all NGOs, including those funded with foreign money.

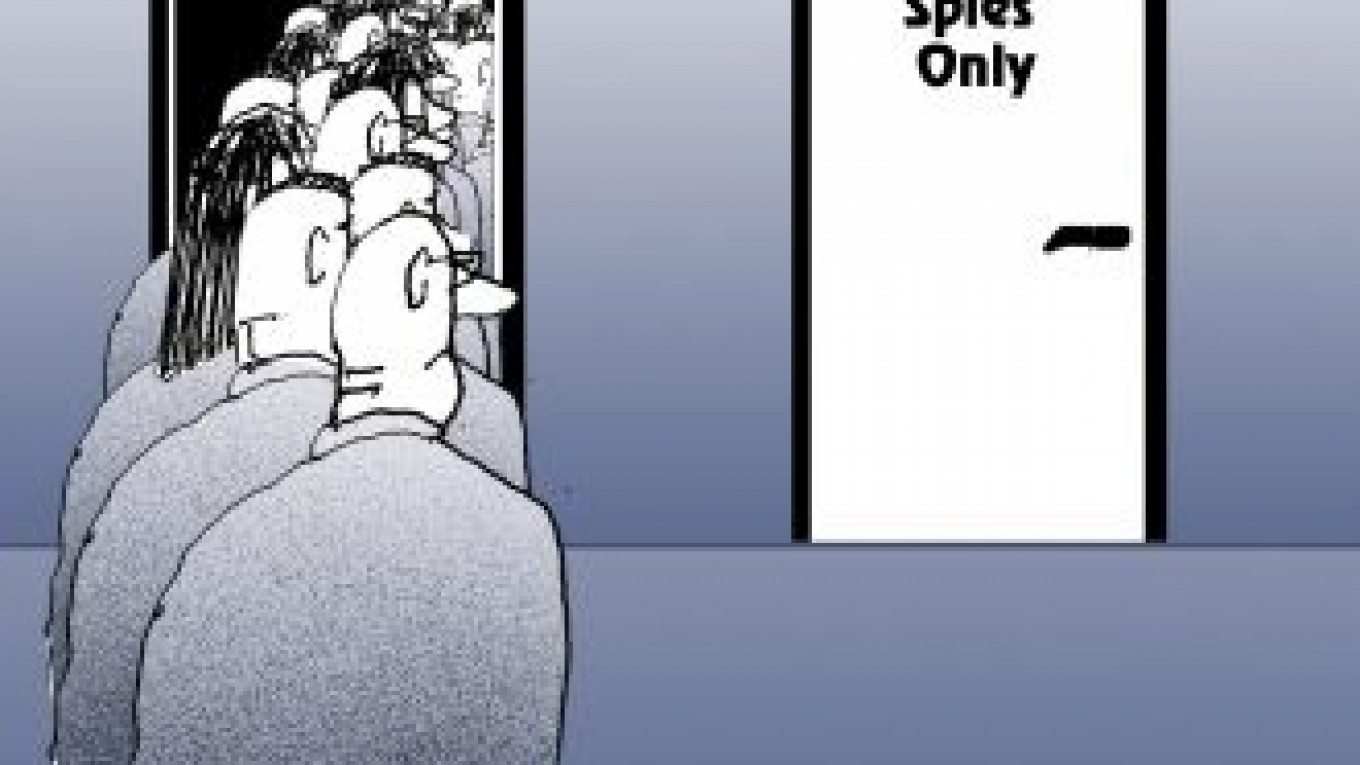

Finally, more than half the respondents in the VTsIOM poll supported the provision in the NGO law to label foreign-funded NGOs "foreign agents," something that was particularly important for Putin. When Mikhail Fedotov, the head of the Kremlin's human rights council, suggested to Putin during a July 10 meeting that the wording in the NGO bill should be softened to avoid the negative association that "foreign agents" has with spies, Putin insisted on keeping the harsh wording. "There is sharp wording in many of our laws," Putin told Fedotov.

From a propaganda and populistic perspective, Putin clearly played his cards right in pushing for the foreign-agent wording in the NGO law. He understands the psychology of the conservative majority, particularly in the regions, that still largely adheres to old Soviet stereotypes: If Russian individuals or groups receive money from abroad, they are likely to be "foreign agents."

Commenting on this phenomenon, Vedomosti wrote in an editorial on Thursday: "Fear of foreigners is called xenophobia and is considered a psychological disorder. Patients who suffer from this illness see foreigners as a threat. The roots of this fear are very old, but countries that are able to overcome this fear become global leaders."

If Putin wants to treat these xenophobic patients and integrate Russia into the modern world, he should stop feeding Russians rubbish about foreign-funded NGOs being a fifth column of foreign agents and jackals who are trying to carry out a U.S.-orchestrated Orange Revolution.

If the Kremlin wants Russia to become a global leader, it should act like one.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.