Dublin native John Delargy moved to Moscow in 2003. He currently works in commercial real estate and has worked with Big Brothers Big Sisters Russia since the organization was established in 2006.

Q: How did you hear about Big Brothers Big Sisters in Russia?

A: I decided I wanted to do something worthwhile outside of my professional and social activities. I saw an advert in the Moscow Times and got in touch with Eric Batsie, the original director of the organization. I thought, if I'm going to be involved, I should really understand what being a "big brother" means. That's when I became a volunteer.

Q: What does your work as a volunteer entail?

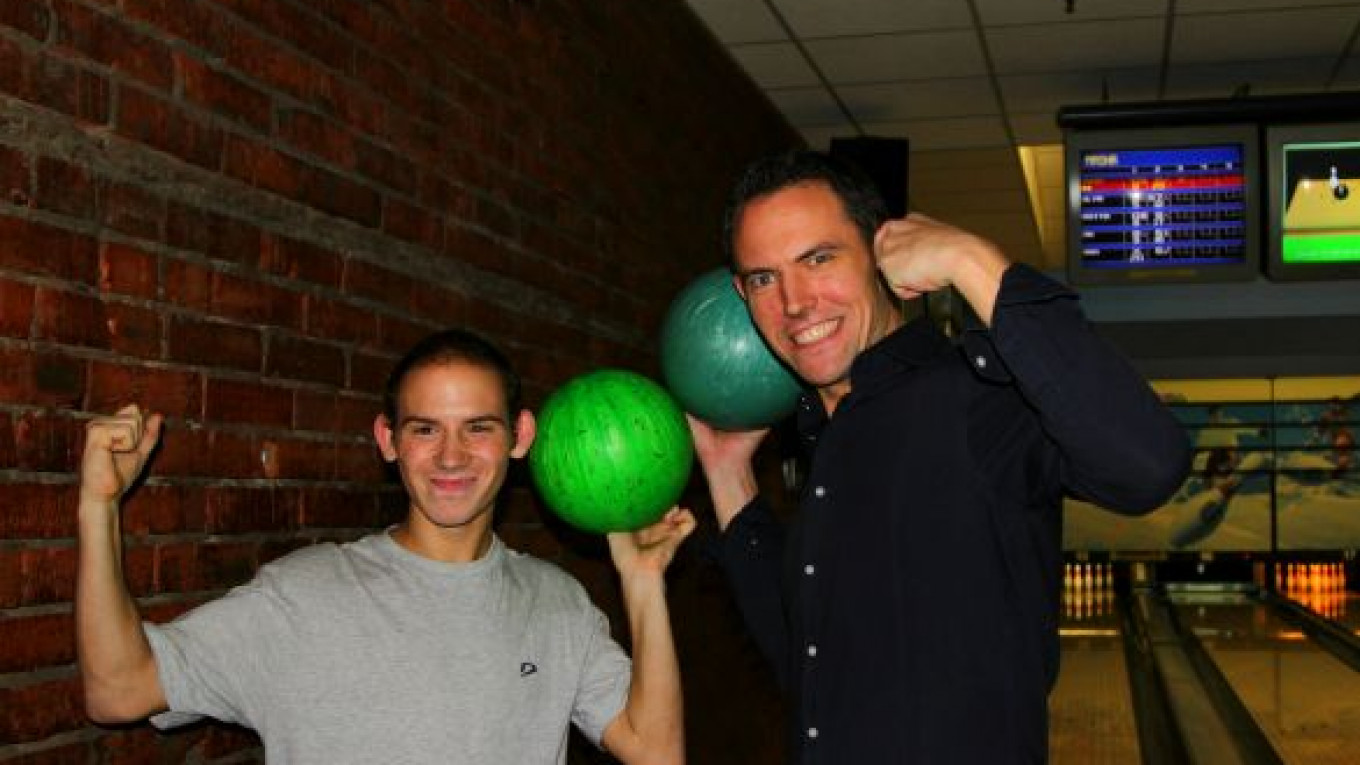

A: They're referred to as "littles." My little brother in the program is called Nikolai. He was 17 at the time we met, and it was his last year in the internat (institution). So basically what it involved was I would go out every week to the internat and just spend three or four hours there, playing football with him and his friends, ice skating and generally hanging around. Then he moved to college to live in the dormitories when he was 18. Once we were free to meet when we liked, where we liked, to do what we liked, the language of the relationship really changed because I was no longer volunteering as a big brother. I no longer had to go out to the orphanage on Saturday afternoon. And now, he is like a brother. I've known him for so long, and we've done a lot of things together.

Q: Is this typical for the relationships that people build through Big Brothers Big Sisters?

A: In Western branches of these organizations, this is exactly how it works. We call them "matches." The big brother might have been 25, the little brother might have been 15 when they first met. Fifty years later, they're still friends. Here the program is only four or five years old so we're, if you like, the first graduates of the program. Once you've gotten into the program and built a relationship with the child, it doesn't just last a year. You become attached to each other and the relationship develops.

Q: Do you ever encounter language or cultural barriers working as a volunteer?

A: I studied Russian so I speak enough to communicate with him. My slang vocabulary has certainly increased. There weren't really that many cultural barriers. We have so many things in common, for example, we both love sports. He introduced me to a lot of Russian music, and we both play guitar and sing. I was outside of my comfort zone quite a bit at some stages, but I can't say there were ever any great cultural barriers. Maybe I was just lucky that Nikolai was such a positive, outgoing young man, and that made the relationship a lot simpler.

Q: What has working with this organization taught you about Russia that you would not have learned from your work or social environment?

A: It opens up a whole new world for you. You see the other side of Russia, which we don't see as professionals in the expat community. There are several hundred thousand orphans in Russia, and the statistics are frightening. Only 10 percent or 15 percent of children who graduate through the orphanage system end up living normal lives. The vast majority ends up either as alcoholics or drug addicts, in jail, or dead.

Q: How can individuals support or become involved with this organization?

A: Get in touch. All it takes is a few hours a week on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon to spend time with a child. What happens is they'll match you. You'll have an interview with the case manager who works with Big Brothers Big Sisters, and they find out what you're interested in. If you're interested in sports or music, then they'll try and find a kid who has similar tastes to you.

Big Brothers Big Sisters holds its Down Under Ball on March 3 in the Renaissance Monarch Hotel. Tickets are 6,000 rubles ($200) each and include a four-course meal, wine/beer/spirits, and live entertainment. Tel. 679-8646.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.