One of the most popular slogans during the December protests in Moscow and other cities was "Putin is a thief!" — and, as Putin himself reminded us in his 2010 televised call-in show, "A thief should sit in jail." This may be one of the main reasons Putin will never step down from power. Ever.

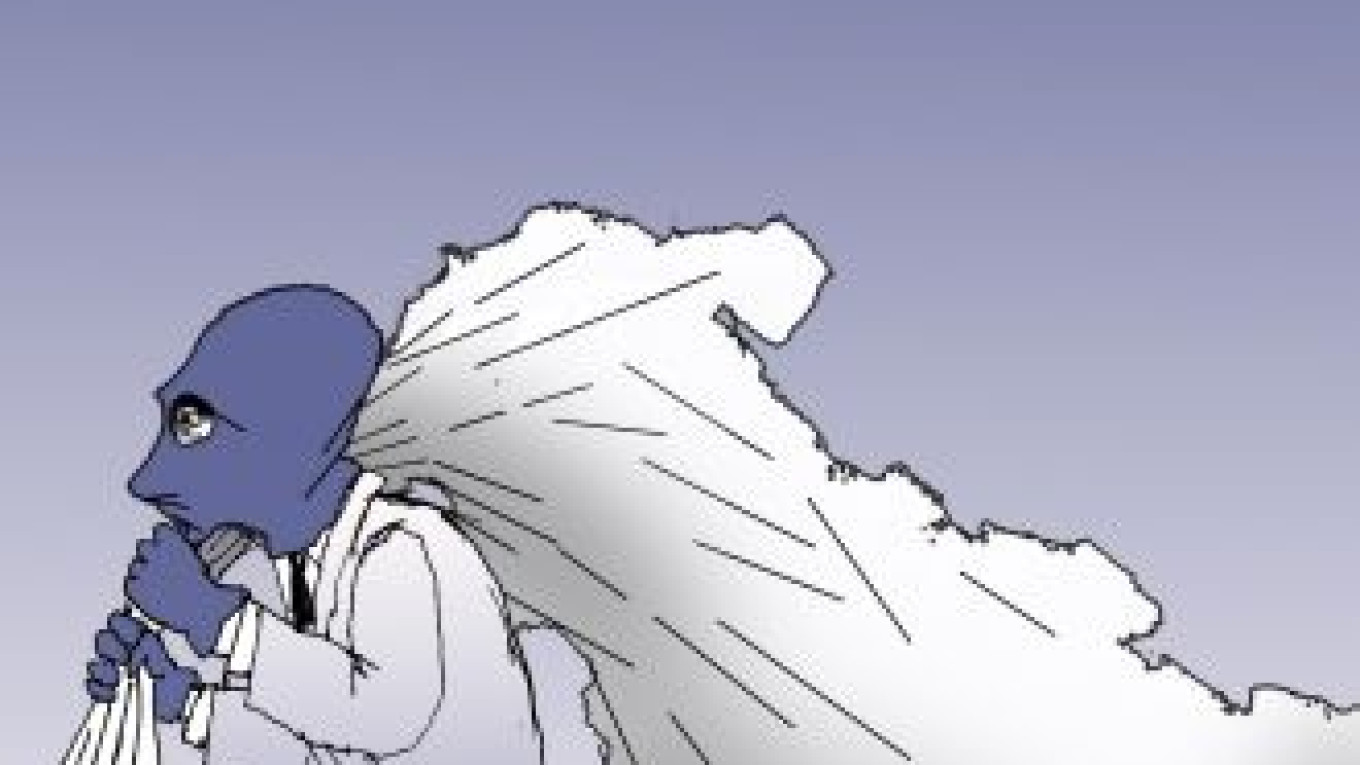

According to The New Times Oct. 31 cover story, "Russia, Inc.: How Putin and Co. Divided Up the Country," Putin and his inner circle control from 10 percent to 15 percent of the country's gross domestic product (from $140 billion to $200 billion) through inside deals. Andrei Illarionov, former economic adviser to then-President Putin from 2000 to 2005, described Putin's "Russia, Inc." as "a corporatist state model." U.S. diplomats put it a little less diplomatically in cables that WikiLeaks published a year ago, describing Russia as "a virtual mafia state" with Putin as the "alpha dog" sitting at the top of this structure.

The best, and perhaps only, guarantee of securing immunity for Putin — and dozens of his friends and colleagues who have become millionaires and billionaires over the past 10 years through their Kremlin-connected businesses — against possible corruption and other criminal charges is to remain in power.

As long as Putin remains in control, Western leaders will continue to do business as usual with him and his administration, and they will ignore or downplay allegations of corruption at the very top. After all, the West has shown many times that it doesn't have a problem having close ties with leaders with shady reputations, such as former Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak or the king of Saudi Arabia, when it is in its best interests.

But imagine if opposition leader Alexei Navalny, for example, ever came to power and Putin becomes just an ordinary citizen. Putin understands that one of the first things Navalny would do after freeing former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky from prison would be to appoint an independent tribunal to investigate allegations of corruption and abuse of power among Putin and his ruling elite.

The Yukos affair alone would probably be enough to put those who conspired to expropriate the country's largest and most-profitable oil company — worth $45 billion in market capitalization before Khodorkovsky was arrested in 2003 — in jail for the rest of their lives. Along with Yukos, the tribunal could investigate corruption charges against Kremlin-connected executives at Gazprom, VTB, Transneft, Russian Technologies, National Media Group, Gunvor, the Rotenberg brothers' enterprises, Bank Rossia, arms trader Rosoboronexport and dozens of other companies that make up Putin's "Russia, Inc."?

How would the West respond? In an effort to support a new, liberal administration, the West could target the Putin era in a showcase battle against a corrupt regime that fell out of favor.

Libya is a good example of how the West can change loyalties 180 degrees when it is expedient to do so. From 2003 to 2010, the West had normal relations with leader Moammar Gadhafi. In 2004, for example, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair hailed Gadhafi as a new ally in the war on terror while helping Royal Dutch Shell secure a deal in Libya worth $500 million. In addition, the United States restored diplomatic relations with Libya in 2006, and Gadhafi had a seat next to Silvio Berlusconi and Barack Obama at the Group of Eight summit in L'Aquila, Italy, in 2009.

But in early 2011, after Gadhafi forces carried out a violent crackdown on tens of thousands of protesters, the West quickly changed sides. It froze $30 billion of Gadhafi's assets; Interpol and The Hague-based International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants against Gadhafi, several of his sons and Libya's intelligence chief; and by July, most of the West had recognized the anti-Gadhafi National Transitional Council as the legitimate government of Libya.

A similar fate could await Putin. The West could conceivably turn against him if protests in Moscow and other cities grow to 500,000 or more people and continue on a regular basis. This happened 20 years ago when the West actively supported Boris Yeltsin against another corrupt and authoritarian regime after hundreds of thousands of his supporters held street protests in August 1991.

In a worst-case scenario, Putin and his inner circle could try to escape justice by fleeing to a friendly country, such as Belarus — not the best place to spend the rest of their lives, but it sure beats a prison cell in Krasnokamensk or even The Hague. If they take enough money with them, they could set up a luxurious retirement community — an enhanced Belarussian version of Putin's Ozero dacha cooperative — and join former Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who escaped corruption charges by fleeing to Belarus in 2010.

The current criminal trial of Mubarak, who is accused of embezzling as much as $70 billion, shows the danger of giving up power peacefully — even when you are 83, dying from cancer and presumably were given an unwritten guarantee of immunity. The conviction on corruption charges against another elderly, ailing world leader, former French President Jacques Chirac, also must have given Putin a slight scare.

Kim Jong Il, however, showed that the best way to preserve immunity from criminal prosecution is by staying in power until death. Putin — no less than Kim, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev or Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko — understands that he can never afford to give up power while he is still alive.

This means that we can expect much more than 12 years of Putin in power. At the end of the next two presidential terms, Putin will only be 72, and at that age he will probably still be in his political prime. What's more, Putin, as he reminded us during his New Year's greetings several weeks ago, was born in the year of the dragon — and, according to Chinese astrologers, those born in dragon years tend to enjoy health, wealth and a long life.

Regardless of whether you believe in astrology or not, this is a bad sign for Russia's future.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.