Monday marks the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and this is a good time to look at the lessons we learned from it.

I recall how I walked into work one day about six weeks after the Berlin Wall fell. A co-worker who was always joking around called out to me as I entered the room, “Have you heard the latest news? There was a revolution in Romania.” “Stop trying to play me for a fool,” I snapped back. “I was just in Romania, and there is no way a revolution could take hold there.” My colleague was offended. “I’m serious,” he said. “They really had a revolution. The army switched over to the demonstrators, and Ceausescu fled Bucharest on Dec. 22.”

That left me speechless. I was in Bucharest in the summer of 1989 attending a summit of Warsaw Pact leaders. As it turned out, this was their last gathering. During that summit, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev tried to convince the leaders of the satellite states to finally begin implementing political reforms. Nobody listened to him, especially not Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu. At that time it seemed that the Romanian dictator’s regime would continue standing for years to come. Not a word of criticism directed at the regime was tolerated. Soldiers toting World War II-era Soviet machine guns stood on every corner, and where once the old neighborhoods of Bucharest had been, now stood gigantic new buildings and enormous vacant public squares. All of this created the impression of a regime standing very solidly on its feet.

Those feet turned out to be made of clay.

Another lesson I grasped at the time was that it is impossible to predict what seemingly trivial factor or incident is capable of sparking a major historical event. When Hungary and Austria opened their borders in 1989, they assumed that a certain number of East Germans would pass from Hungary into Austria and from there into West Germany. But nobody was prepared for the tens of thousands of East Germans who flooded through, causing traffic jams hundreds of kilometers long in their desire to reach West Germany at any cost. The impression created by the mass flight of East Germans from the “socialist paradise” was so strong that East German leader Erich Honecker quickly found himself on a “well-deserved vacation,” which in Soviet parlance meant forced retirement.

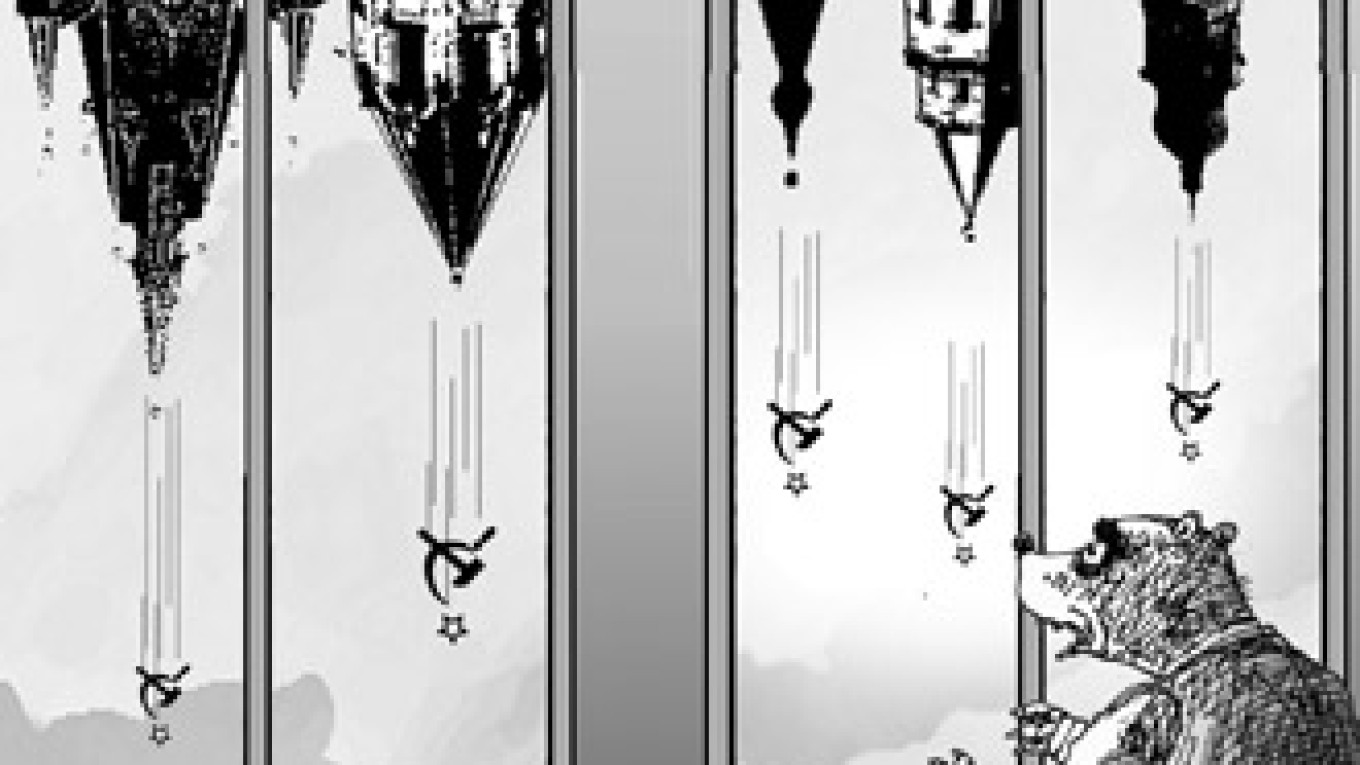

Another lesson was that Moscow was ultimately doomed by its traditionally condescending attitude toward the Warsaw Pact leaders, typically saying, “Where could they possibly go to get away from us? We will pressure them, explain our actions, and they will understand and do everything just as we want.” The challenges and warnings Gorbachev issued went unheeded, East German leaders dug in their heels and steadfastly refused to make the slightest change to their domestic policies until the situation had grown out of their control. And when attempts were finally made to install a more moderate, reform-oriented leadership in East Germany, it was too late. At that point, the East Germans did not want to see another communist in power. The same scenario was repeated soon afterward in Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia.

Two days before the Berlin Wall fell, while most of the Soviet Union was celebrating the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, an alternative demonstration was held in Moscow by people who wanted to see Gorbachev’s reforms extended and deepened. Gorbachev had no plans to leave the Communist Party, believed that it was possible to build “socialism with a human face” and was therefore ready to celebrate the Nov. 7 holiday under the banner of democratic slogans. My late father loved to recall 1927, when he had only just arrived in Moscow as a boy, and how two separate rallies took place on Nov. 7 — one in support of Josef Stalin, and the other in support of the opposition headed by Leon Trotsky. In 1989, I was so struck by the fact that we were seeing the first such demonstration in Russia to have taken place in the last 60 years that whatever was happening in Europe at the time simply paled in comparison. And yet, how can one compare the significance of a march by several thousand people demonstrating for a “democratic Russia” with the fall of the Berlin Wall — a structure that had symbolized the division of the world into two competing systems, and the demolition of which led to a domino effect that caused one communist regime after another to fall in Eastern Europe?

But the Soviet Union had its own serious problems at the time. It was bogged down in a deep political and economic crisis, and was shocked by the determination shown by Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Georgia to break free from the Soviet Union. In addition, the Kremlin was deeply concerned about the first flare-ups of interethnic conflicts in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Soon-to-be President Boris Yeltsin was planning to launch a struggle for power over the Russian Federation, the largest of the 15 Soviet republics. Gorbachev was preparing for yet another confrontation with democratic opposition leader Andrei Sakharov, who spoke out stridently against the Soviet leadership that had grown increasingly slow, wavering and erratic. Nobody knew that Sakharov had only little over one month to live, that Gorbachev’s days in power were numbered, and that with his departure, the Soviet Union would cease to exist.

And certainly not a soul could have known during those fateful days in November 1989 that a fair-haired young man with the obscure surname of Putin — who, pistol in hand, had dispersed a crowd of demonstrators outside the building housing the Dresden branch of the Soviet KGB — would 10 years later become Russia’s second president.

Yevgeny Kiselyov is a political analyst and hosts a political talk show on Inter television in Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.