To see the designs -- many of them more outlandish than the resulting buildings -- behind the Soviet reconstruction of Moscow, pay a visit to an eye-popping exhibit at the Shchusev Architecture Museum, where the work of two major Soviet architects, Dmitry Chechulin and Alexander Vlasov, is on display.

Chechulin is responsible for a number of grandiose buildings in Moscow, including the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall and the Pekin Hotel. He also played a major role in the famous story of the Christ the Savior Cathedral and its architectural successor. When the cathedral was razed in 1931, an international competition was launched for a design for a Palace of Soviets to be built on the site. The palace was to be the architectural center of Moscow, the administrative equivalent of the Kremlin and the focal point for a series of vysotki, or skyscrapers, which were still to be built.

The competition was won by Boris Iofan, whose outrageous Christmas-cake design topped by a 100-meter statue of Lenin was irresistible to the judges. Iofan's design dwarfed the tallest Kremlin towers three times over, which can be seen in a drawing by Chechulin of the embankment of the Moscow River. Due to political infighting, only the foundations for the Palace of Soviets were laid, and several years later, Chechulin was asked to design the swimming pool that was installed in the foundations.

Chechulin's architectural drawings are a marvel. They tower over the visitor -- an effect he also sought in his buildings -- and are spellbinding and surprising in their depiction of Moscow as a clean, sunny city. Chechulin was one of the strongest proponents of the neoclassical style that was so popular with Stalin and Mussolini. He was also one of the architects behind the towers now known as the Seven Sisters or Stalin's Wedding Cakes. While he was the city architect of Moscow from 1945 to 1949, he oversaw the construction of the seven landmark skyscrapers, one of which, on Kotelnicheskaya Naberezhnaya, he designed and subsequently lived in.

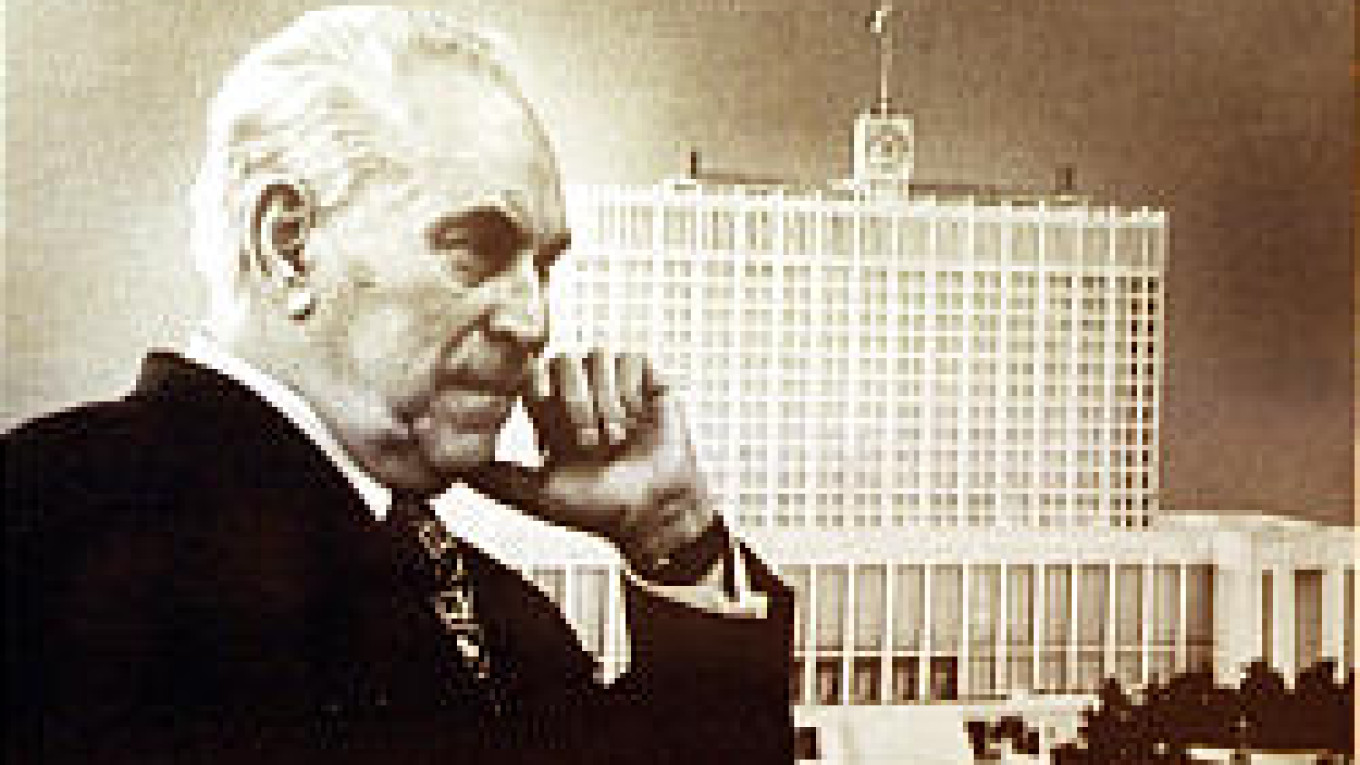

Chechulin also threw his creative powers into the competition to design the building for the Aeroflot headquarters, which was to be on Belorusskaya Ploshchad. Two paintings of his vision, one in daylight and one at night, hang opposite each other at the exhibit. All the architect's favorite motifs are here -- round windows, arcades topped with statuettes and liberal use of the symbols of empire-building such as flags, laurel wreaths and friezes of Soviet victories. The Aeroflot building was yet another glorious fantasy never to be constructed. Instead, Chechulin toned down the design, and thus the White House was born.

If Chechulin had had his megalomanical way, a vysotka would tower over Red Square behind St. Basil's, and GUM would not be a temple of consumerism, but a momentous war museum, built on such a scale that the visitor would feel smaller than a flea. Luckily, he was restrained and his fantasy kept within the confines of elegant metro designs, built to make average Muscovites, many of whom lived in matchbox-sized apartments, feel as if they were taking a stroll in a palace. Chechulin was a master of this, as seen in his interior of the Komsomolskaya metro station on the Sokolnicheskaya line. One building that unfortunately did not remain a doodle on his drawing board is the Rossiya hotel, an architectural sore thumb amid the pre-Revolutionary buildings near the Kremlin.

Alexander Vlasov was an architect with as much vision as Chechulin but less pomp; he was more interested in form than decoration. He was the city architect of Kiev during its postwar reconstruction, and then he took over as the city architect of Moscow after Chechulin stepped down, serving from 1950 to 1955.

His work on Khreshchatyk, the main street of Kiev, defines the Ukrainian capital to this day. Vlasov made concessions to the playful spirit in Ukrainian architecture, decorating many of the buildings with glazed and engraved tiles. However, even in the drawings, this cannot disguise the unfortunate fact that they are gargantuan Stalinist blocks.

Vlasov is a giant of Moscow architecture; he designed many of the big postwar constructions in the southwest of the city, including Luzhniki Stadium, the Krymsky Bridge, which is the longest suspension bridge in Europe, and Gorky Park. Vlasov, the son of a forester, was perhaps most in his element in landscape design. It is he we have to thank for Gorky Park's over-the-top fountains and cascades that were his vision of a peaceful oasis in the center of Moscow. After decades of summer walks and winter skating, the park gradually has become a peeling monument to kitschy neoclassicism.

One of Vlasov's most successful and moving designs is his monument to Ukrainian Jews massacred by the Nazis during World War II. It is a granite pyramid on the site of Babi Yar, a huge concentration camp where thousands met their deaths. The sketches for the memorial are somber, yet beautiful. Vlasov originally wanted to use the religious image of the Piet? on the tomb, but confined by the demands of Soviet ideology, he settled for a commemorative inscription within a laurel wreath.

It is always fascinating to see the buildings that might have been -- but weren't -- an architect's unfettered visions of a dream city. Chechulin's stunning drawings give us an insight into his megalomania, but the visitor will be glad that some of his designs did not leave the drawing board. Vlasov was a milder man, as several self-deprecating portraits here illustrate. Both have left their stamp on the city: The positive legacy of Chechulin is to be found in his designs for the metro, admired worldwide for their idiosyncrasy and elegance, and Vlasov's town planning still defines large areas of the capital.

"Exhibit for the 100th Anniversary of Architects Alexander Vlasov and Dmitry Chechulin" (Vystavka k 100-letnemu yubileyu D.N. Chechulina i A.V. Vlasova) runs to April 15 at the Shchusev Architecture Museum, located at 25/5 Ulitsa Vozdvizhenka. Metro Biblioteka Imeni Lenina, Alexandrovsky Sad, Arbatskaya. Tel. 291-2109.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.