Using a wide variety of sources, including archival materials, oral interviews, government proclamations and propaganda, memoirs and fiction, Kelly divides her book into three main parts. In the first part, she relates how government officials, educators, writers and parents perceived children, particularly in European Russia (of the many non-Slavic minorities in Russia, only Jewish and Tatar children receive attention). The second part deals with homeless and institutionalized children, including those in correctional facilities. In the third part, Kelly discusses children in the family and schoolroom settings. She concludes by examining the transition from childhood to the late teenage years (especially with regard to sexuality and romance) and by turning to the post-Soviet period.

Although it is difficult to present such an impressive amount of scholarship in lively, page-turning prose, Kelly does her best to sustain the reader's interest. Building on her clear writing and organization, she intersperses her narrative with personal reflections culled from oral interviews and memoirs, and with over 100 illustrations (most of them excellent). History also does its part by providing Kelly with interesting ironies. Among the posters Kelly reprints from the years of Stalinist repressions is one on the cover that proclaims, "Thank You, Beloved Stalin, for a Happy Childhood!" Similarly, she reminds us that Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the feared Soviet secret police, supposedly possessed "a legendary love of children," and once "vehemently exhorted" his sister "to avoid harsh punishment." The leading children's store in Moscow, Detsky Mir, or Children's World, was later established on Dzerzhinsky Square facing KGB headquarters.

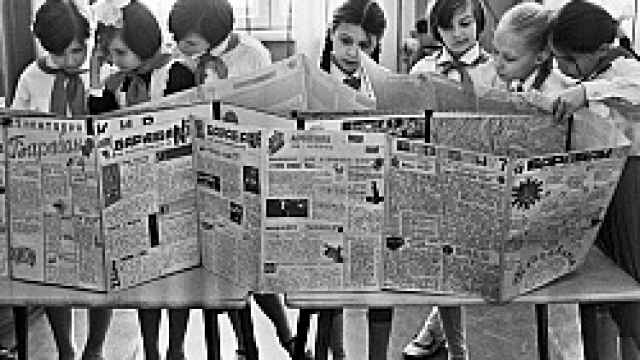

Itar-Tass Members of the Young Pioneer organization gather around their school's newspaper, baraban, in 1971. | |

Kelly previously authored a book on the murdered teenager Pavel Morozov, who was made a hero in the 1930s for allegedly denouncing his ideologically deviant father, but she also has written first-rate studies of 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature, women writers and advice literature. And here she frequently quotes and refers to Russian writers and child-care experts. For example, she often mentions Kornei Chukovsky, whose many talents included writing for children (a topic Kelly often addresses) and Anton Makarenko, whose how-to-bring-up-your-children "Book for Parents," first printed in 1937, remained popular for decades and is still available in? English translation. Kelly also notes the different ways in which boys and girls were raised and how children's social positions affected their upbringing. She notes, for example, that many of those she interviewed complained that, during the Brezhnev era, teachers treated working-class children less well than those from more privileged families.

Dividing her examination into four historical periods to emphasize the changes that each era brought for children, Kelly nevertheless points out the continuities and deals with what the historian Marc Raeff has called "the messiness of history." She does not attempt to squeeze all her facts into neat categories, but rather acknowledges exceptions to general patterns. This is especially important given that government intentions regularly went unrealized, and the gap between propaganda and reality was often wide. The Soviet state might, for example, urge parents to bring up their children according to what it considered to be scientific, rational, Marxist-Leninist principles, as opposed to more traditional (often religious) practices, but "in peasant households, the old ways went on until at least the Second World War."

One overall impression left on the reader is that caring for children in modern Russia was much more difficult than in most Western countries. "The priority for most parents during the first four decades of Soviet power," Kelly writes, "was to ensure that their children got a sufficiency of food of any kind." Kelly documents the tremendous toll on children of such historical factors as economic and educational backwardness, tsarist and Soviet inefficiencies, wars and revolution, famine and Stalinist purges. In a section titled "The Battle with 'Backwardness,'" we read that the death rate among European Russian newborns in 1913 was 283 per 1,000, and that the film director Alexander Dovzhenko was "one of just two surviving children out of 14." During the Leningrad Blockade, which took a million Soviet lives during World War II, children similarly bore much of the suffering, including starvation.

Also significant was the fact that "the Soviet state placed children's affairs at the heart of its political legitimacy, emphasizing that children were treated with greater care than they were anywhere else in the world." Although the late tsarist period witnessed increased government and private volunteer efforts to improve child care, the new Communist government greatly stepped up attempts to instruct families on proper child-rearing techniques and expanded state controlled child-care efforts beyond the family, including in schools and preschool programs. By the time Gorbachev came to power in 1985, the Soviet record was certainly a mixed one. From then until the present, the plusses and minuses of it, as well as post-1985 developments, have continued to be debated, as Kelly sums up nicely in the last chapter of this indispensable source on the world of Russian children during the 20th century.

Walter G. Moss teaches history at Eastern Michigan University and is the author of "A History of Russia" and "An Age of Progress? Clashing Twentieth-Century Global Forces."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.