Forget Maurizio Cattelan’s $150,000 banana, duct-taped to the wall at Art Basel in Miami last week and eaten by a less well-known trickster artist. (The buyers of the artwork are fine with that — it came with a manual that prescribes replacing the fruit every week or so, anyway.) The best art of this type comes from Russia, because there, it actually means something.

The art object that, as any responsible critic should recognize, eclipses Cattelan’s headline-grabbing “Comedian,” was sold online on Dec. 9 for 1.5 million rubles ($23,600). It was created by Artem Loskutov, an artist from Novosibirsk, Russia, who started the now nationwide tradition of “Monstrations,” annual rallies where people carry nonsensical signs. (“We Can’t be Knocked Off Course: We Don’t Know Where We’re Going,” one said this year.)

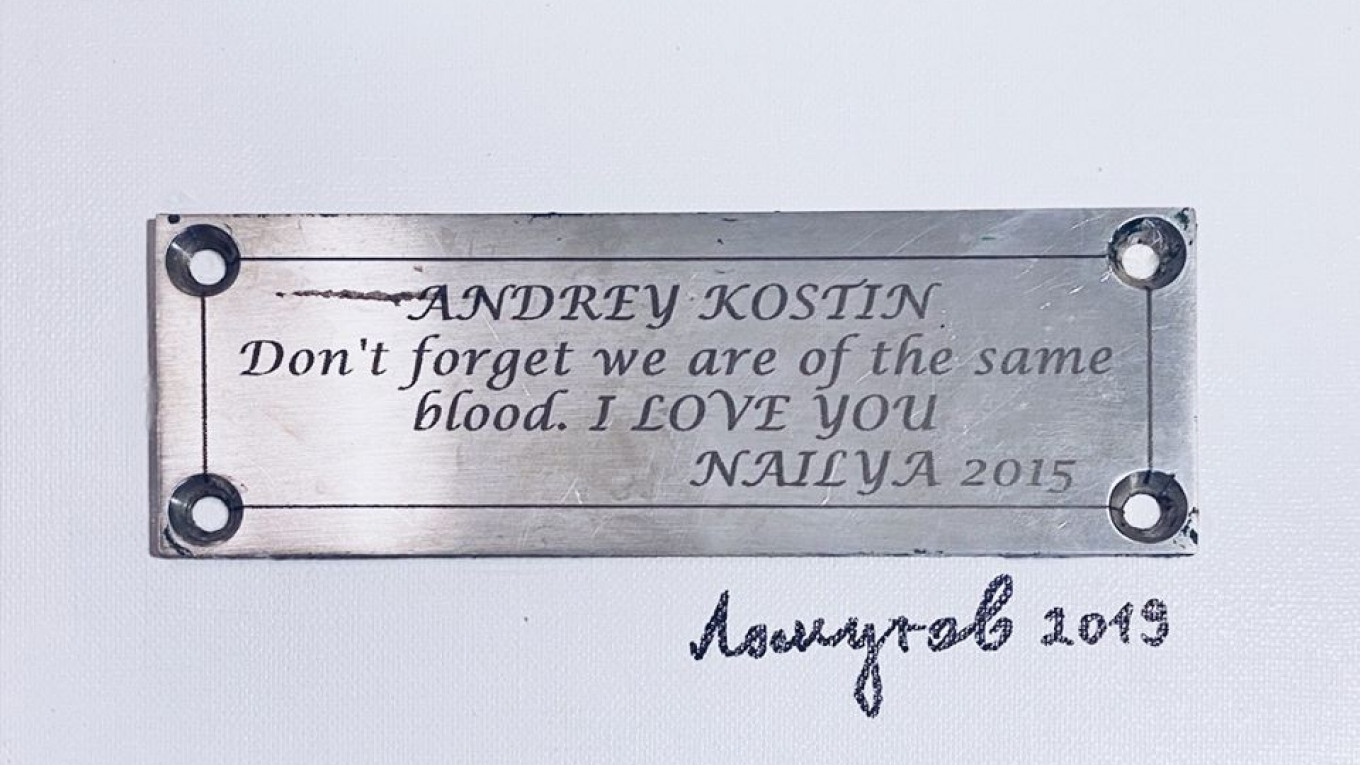

The object is a piece of canvas-covered cardboard with a steel plaque glued to it and Loskutov’s signature, in marker, underneath. On the plaque, a woman named Nailya professes her love for a man named Andrey Kostin, in English, and tells him, “We are of the same blood,” an apparent corruption of the line from Rudyard Kipling’s “Jungle Book,” “We be of one blood, ye and I.”

Loskutov’s description of the materials used in creating the work says, “found object, stainless steel, 5X14 cm; marker, canvas on cardboard.” But the plaque is, strictly speaking, a stolen object, not a “found” one. Until a few days ago, it was affixed to one of the 6,800 benches in New York City’s Central Park “adopted” by donors to the Central Park Conservancy.

It came from what’s probably now the most famous of these benches: Earlier this month, it got a prominent mention in a 29-minute video by anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny, an arch-foe of Russian President Vladimir Putin, that has been viewed more than 5 million times (and counting) on YouTube. The video is dedicated to the relationship between Andrey Kostin, the (married) president and chief executive officer of the state-owned bank VTB and state television anchor Nailya Asker-Zade. The state banker, according to Navalny, has showered Asker-Zade with expensive gifts, including prime real estate and the use of a yacht and a private plane. The cost of it all appears to be too high even for Kostin’s significant legitimate income, Navalny wrote.

Kostin hasn’t commented on the video, nor has VTB, Russia’s second biggest bank by assets. Asker-Zade, known for her fawning interviews with members of Putin’s close circle, thanked Navalny on Instagram for the publicity.

Navalny’s made-for-YouTube investigations are political tools rather than journalistic endeavors, and much of the film’s substance should probably be classed as opinion rather than fact. But when it comes to the Central Park plaque, Asker-Zade is mentioned in Central Park Conservancy’s 2015 annual report among donors of between $10,000 and $24,999. Navalny specializes in exposing impossibly lavish lifestyles that embarrass Putin allies and scandalize the average Russian. Judging by his video’s viral spread and the indignant comments it’s spawned on social networks, he handily hit his mark here.

To put his allegations in context, Navalny wrote in a separate post that by his count the total value of the gifts is comparable to the amount that’s been raised by Rusfond, one of Russia’s biggest charities dedicated to funding medical treatment for seriously ill children, over its 23-year history. That would be difficult to prove, but is important for what happened next.

Suddenly, the plaque disappeared from the bench, an event Navalny was quick to report on Twitter. On Dec. 9, it resurfaced in Loskutov’s possession. To turn it into art, Loskutov didn’t just paste it on cardboard and scribble his name underneath. He promised to donate the proceeds from its sale to Rusfond.

The same day, he announced the object had fetched 1.5 million rubles in an informal auction he had run online. (The original screws from the bench were offered as a bonus.) To complete the performance, proof of the transfer to Rusfond is still needed. But Loskutov’s work has already garnered numerous comments to his tweets and Facebook posts — both accusing him of theft (even many Putin foes were uneasy about this) and praising him for his audacity. One commentator summed the whole situation up like this: “They stole our money and we’ll steal their memories.” Although there's no proof Asker-Zade or Kostin engaged in theft.

On Tuesday, Loskutov took to Facebook and Twitter again to post a quote attributed to a host of greats, most often to Pablo Picasso: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” It’s unclear, though, if he meant himself or the bureaucrats and managers of state-owned companies whom Navalny often accuses of graft.

The New York Times’ art critic Jason Farago recently offered what he called “a reluctant defense” of Cattelan’s banana on the basis of the artist’s “willingness to implicate himself within the economic, social and discursive systems that structure how we see and what we value.” If that defense is valid, Loskutov’s action works on more levels than Cattelan’s work. It’s art as Robin Hood-style theft, art as tabloid journalism, art as political protest, art as social commentary, art as commerce and art as charity all rolled into one. It’s not a case of art imitating life or the other way round, but art’s bold intrusion into life as it plays out under one of the world’s most dispiriting authoritarian regimes.

Loskutov’s performance, whatever its consequences for him, deserves a place among other audacious Russian art works such as Voina Art Group’s 2010 depiction of a gigantic penis on a St. Petersburg drawbridge exactly opposite the secret police office or Petr Pavlensky nailing himself to the pavement on Moscow’s Red Square in 2013. It’s easy these days to be cynical about the value of art and to play tricks on audiences based on the amount of money some wealthy people are willing to pay for fatuous objects. It’s much riskier, and much more meaningful, to challenge allegedly corrupt elites and the enforcers and benefactors of authoritarian nations. Where political opposition is feeble, art has a role to play.

This article was first published in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.