This article was originally published by EurasiaNet.org

Kyrgyzstan is preparing to mark the centennial of a historical tragedy that nationalists in Bishkek are portraying as a Russian-led genocide. The commemoration is causing unease in the Kremlin.

In the summer of 1916, Kyrgyz nomads rose up against a World War I-era conscription drive imposed by Tsar Nicholas II's government. When Cossacks loyal to the tsar put down the rebellion, thousands of Kyrgyz undertook a fateful exodus over snowy passes to China. Local historians claim the resistance and the "Great Flight" — or "Urkun," as it is known in Kyrgyz – left over 100,000 Kyrgyz dead. The events, which were glossed over in Soviet textbooks, remain contested.

A May 27 presidential decree on the anniversary hints at difficulties in striking a balance between nation-building efforts focused on the country's ethnic Kyrgyz majority, preserving national harmony in a country with a significant Russian minority, and not offending Moscow.

"Massive unrest in Kyrgyzstan took on the character of a rebellion not against the Russian people, but against tsarist colonialism," reads the decree, signed by Kyrgyzstan's Kremlin-leaning president, Almazbek Atambayev. Society needs "an objective historical evaluation of the reasons and consequences of what happened."

But 1916 has become a political football in parliament. Nationalists are demanding documentaries should be produced to expose Russian misrepresentations. Opponents of Russia's Eurasian Union – which Kyrgyzstan has now all but joined – are saying that Moscow's integration project is a revival of a Kremlin-led empire.

The Russian Foreign Ministry's Gorchakov Foundation – named for Alexander Gorchakov, a tsarist-era foreign minister – agreed last year to fund research on the "restoration of historical facts" connected to the tragedy. The organization under consideration to lead the research project is none other than a group of local Cossacks.

According to a source close to policymaking circles in Kyrgyzstan's government, the fact that the Gorchakov Foundation is considering the Cossacks to implement the project has sent Kyrgyz officials "in a rage".

"For Russia, it is important to get its version of history across after [the propaganda-fueled war in] Ukraine," said the source, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the topic. "But this is quite dangerous."

A Cossack leader declined to comment. The Gorchakov funding has not yet been disbursed.

The call for greater attention to the events of 1916 comes as Kyrgyzstan tries to shake off perceptions it is again becoming a Russian colony. On June 2, officials at the country's main civilian airport detained Mustafa Dzhemilev, the leader of the Crimean Tatars in Ukraine and a Ukrainian parliamentarian, as he arrived for a conference. Dzhemilev later claimed on Facebook that his detention was "on the orders of the owners of Kyrgyzstan, located you know where" – an obvious reference to Moscow, which has taken a hardline attitude to Tatar activism since its annexation of Crimea last year.

Kyrgyzstan's Foreign Ministry bristled in a statement the following day, calling Dzhemilev's words "insulting in relation to the sovereignty of the Kyrgyz Republic," which "no-one can place in doubt."

Sensitivities about statehood run deep in Kyrgyzstan.

Nationalist MP Jyldyz Joldosheva believes the Great Flight remains a "vital component" of the statehood Dzhemilev publicly doubted.

"Lately, it has become fashionable to distort history. How truthfully will the Gorchakov Foundation study this event? This is a big question," Joldosheva said. "After all, this event – when Russians destroyed Kyrgyz – was seen by eyewitnesses who are still alive!" She declined to provide contact details for the witnesses.

Joldosheva, whom many accused of fueling nationalist hatred with provocative statements in the wake of 2010's deadly ethnic clashes between Kyrgyz and minority Uzbeks, was a key backer for the 2014 nation-building historical epic "Kurmanjan Datka: Queen of the Mountains," which Kyrgyzstan had hoped would win an Oscar. Now she says she wants to make a documentary on the Great Flight.

"Without history you cannot build the future," said Joldosheva. "I believe it was genocide."

Elsewhere in parliament, the vocal minority that opposed Kyrgyzstan's entry into Russia's Eurasian Union likens accession to absorption by the Russian Empire in the 19th century.

"Today Russia has an acute imperial illness," local media quoted parliamentarian Omurbek Abdyrakhmonov as saying, explaining his vote last month against accession. Abdyrakhmonov is sitting on a commission set up by the political opposition to study the 1916 events. The commission has pledged to cooperate with a parallel, government-appointed working group.

On the whole, Kyrgyzstan remains solidly pro-Russian. A June 17 Gallup poll showed 78 percent of Kyrgyzstanis support the Kremlin's policies, behind only Tajikistan (92 percent) in the former Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, the anniversary "comes at a strange time," said Medet Tiulegenov, director of the International and Comparative Politics Department at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek.

"With Ukraine and the expansion of the Eurasian Union, there is a lot of discussion about Russia's relationships with its periphery. So it is quite awkward for Moscow," Tiulegenov told EurasiaNet.org.

And what is awkward for Moscow is awkward for Atambayev, who finds himself caught between an assertive Kremlin and his country's restive political elite.

"Perhaps [Atambayev] is trying to position himself as an ideological president," mused Tiulegenov. "Or perhaps he is only promoting the [commemoration] because if he does not, others will make it their own."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

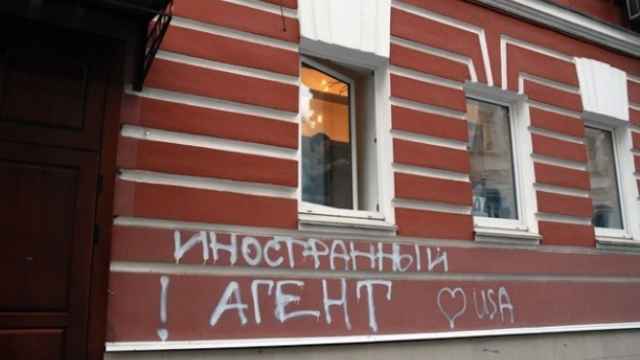

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.