Nothing burst and everything is working." Thus spoke President Vladimir Putin during his annual call-in program last week. It's certainly not the best quote we've heard from a man famous for his pithy formulations and sarcastic jibes, but it's a pretty decent summary of his view on Russia's economy.

As he faced the nation, Putin was much more optimistic than he has been over the past few months, proclaiming that the worst of the crisis has passed and that Russia would return to "normal" growth in less than two years. According to the Kremlin, then, the economic war against Russia is over, and Russia won.

Putin very well might, as German Chancellor Angela Merkel put it, live in "another world." Certainly his statements about Ukraine have very little basis in objective reality, and it would be exceedingly foolish to simply take his upbeat proclamations at face value.

In this particular instance, however, Putin really doesn't seem to be that far off of the mark. The idea that Russia's economy could already be emerging from the recent crisis is not a Kremlin conspiracy.

Western outlets like Newsweek have also featured upbeat stories about Russia's unexpectedly robust economic performance. Even people who are critical of Putin and Putinism, like Bloomberg View columnist Leonid Bershidsky, have noted that Russia's current downturn might not prove so bad after all.

Financial professionals are not quite as upbeat as the Russian government, of course, but have gone on the record with expectations that the economy will bottom out in the second or third quarter and cumulatively shrink by somewhere between 3 and 4 percent. A few individual forecasts (like Standard & Poor's) now predict a hit to Russian gross domestic product of only 2.6 percent.

This relative optimism is very different compared to how the situation was just a few months ago. Back in December and January it really did look like the bottom had fallen out from under Russia.

The currency was in a death spiral, oil prices were plumbing new lows on a daily basis, the heavily indebted corporate sector was cut off from the international capital markets, and the banking system was in need of such massive bailouts that even the country's famously robust international reserves might prove insufficient. Everything that could be going wrong was going wrong.

As a reminder of how bad things looked, The Washington Post's Wonkblog, which as the name suggests is an outlet primarily focused on numbers analysis and not partisan shouting, published several articles with headlines like "Remember Russia? It's still doomed."

This was not an outlandish forecast. Anders Aslund predicted that Russia's current crisis would be far worse than the one it experienced during 2008-09 and that it would suffer a "financial meltdown" paired with an "8-10 percent decline in output."

What, then, to make of the current situation? What useful lessons can we draw?

The first is that we underestimate the capability, flexibility and creativity of Russia's monetary authorities at our own peril. To date, the Russian Central Bank has managed the seemingly impossible task of staunching the ruble's decline without sparking ruinous hyperinflation or totally collapsing the rest of economy.

Personally, I didn't think that they would be able to do this. It certainly wasn't pretty, and it required the use of some highly unconventional tactics, but Elvira Nabiullina and her team have put on a tour de force. Many parts of Russia's government bureaucracy remain mired in dysfunction, corruption and chaos, but the Central Bank would appear to be operating at a world-class level.

The second is that Russia's economy, despite its many and glaring faults, is a lot more flexible than its Soviet predecessor and is not going to collapse in the near future.

No, there hasn't been rapid import substitution as predicted by the Kremlin: Despite quite a lot of boasts from the political leadership about how "domestic producers" would benefit from the ruble's recent devaluation, Russian industrial production in the first quarter of 2015 was actually 0.4 percent lower than it was in the first quarter of 2014. A 0.4 percent decline is hardly something worth boasting about.

But the Russian economy has been able to adapt to the changing external circumstances much more rapidly than anticipated in the West, where it is common to think of Russia as a barely changed version of the lumbering and wasteful Soviet Union.

The panic that seemed to grip the Russian corporate sector at the start of the year did not lead to a rapid fall-off in production the way that it did in the winter of 2008-09. While some Russian firms, particularly the banks, are likely to need additional government help, many others are basically healthy. Not thriving, by any means, but also not in danger of collapse.

In case any of the above is unclear, Russia's unexpected economic resilience does not mean that it was "right" or that it is some kind of model to be imitated. It simply means that Russia is more resilient in the face of economic pressure than was assumed to be the case.

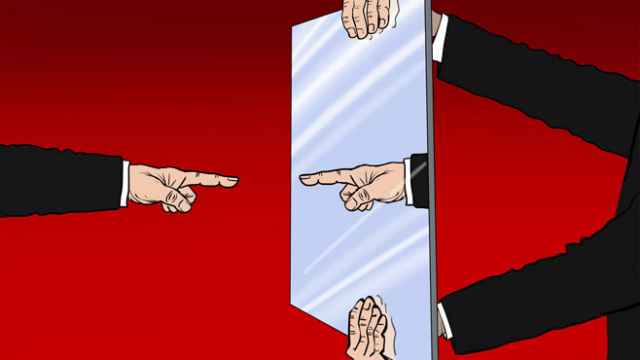

Economically speaking, Russia is clearly worse off than it was before sanctions were introduced, but it is not so much worse off that it will simply cave to Western demands. And that, after all, was supposed to be the point of sanctions: not simply to hit Russian consumer in the pocketbook, but to convince them that their government was acting inappropriately and that its policies needed to change.

Could that happen in the future? Yes. But to date, the pain caused by sanctions has not been of nearly the magnitude required to fundamentally alter the Russian government's calculus.

Mark Adomanis is an MA/MBA candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Lauder Institute.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.