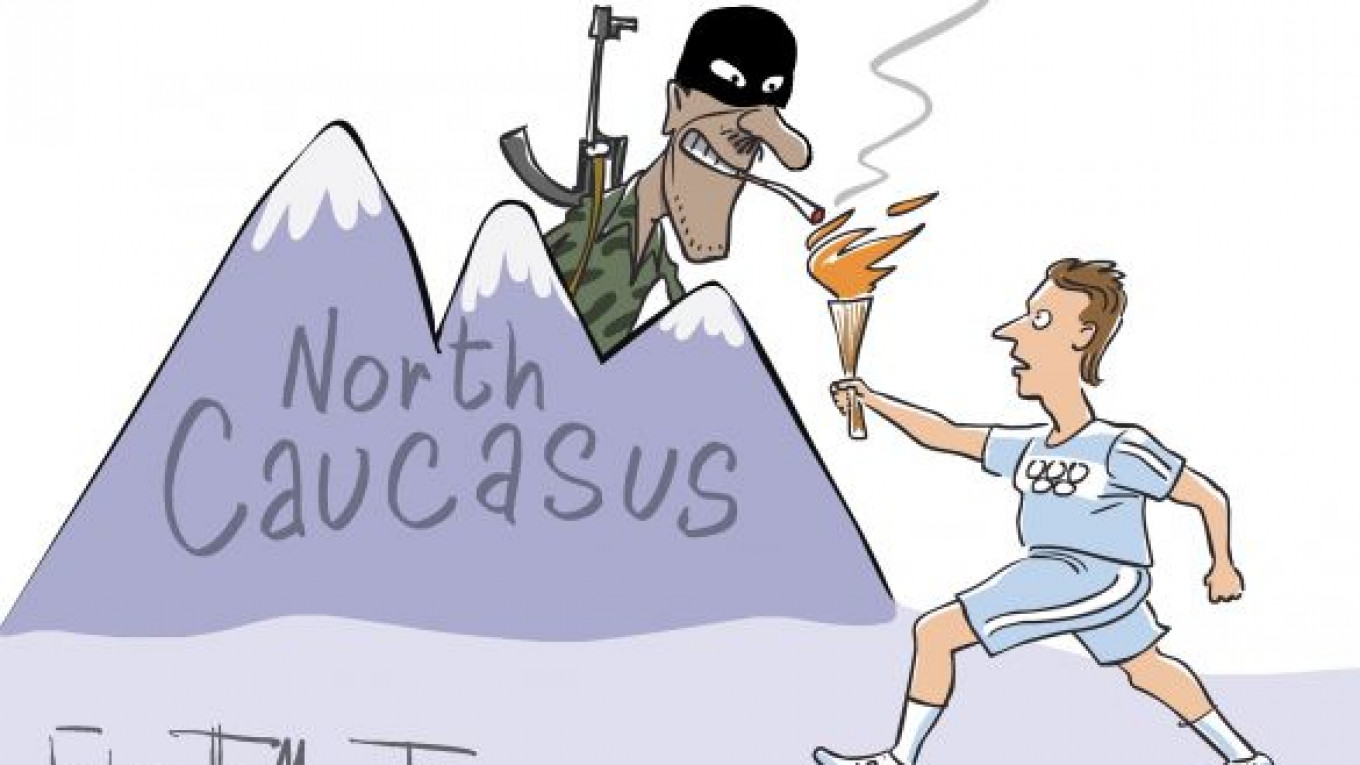

Russia's Islamist insurgents may attack the Sochi Winter Olympics with drones.

These will not be like the drones used by the Americans, armed with Hellfire missiles. Rather they will be jerry-rigged unmanned ariel vehicles, or UAVs, of the sort easily available online for a few thousand dollars. Such remote-controlled UAVs are probably unstoppable at low altitudes and will not need much armament to cause mayhem.

The closing ceremony for the Sochi Olympics will be Feb. 23, the day that marks the 70th anniversary of the deportation of Chechens, Ingush and others from their homelands in the North Caucasus. That choice was either an act of colossal ignorance or colossal arrogance.

The Chechens, in particular, have already proved innovative in pioneering new methods for inducing terror. In fact, they are credited with the first, and so far the only, instance of nuclear terrorism. In November 1995, Chechen rebels buried a dirty bomb — cesium 137 wrapped around dynamite — in Moscow's Izmailovo Park. The media was alerted and the unearthing of the bomb was televised live, possibly spreading as much fear as if it had actually exploded. A UAV carrying a similar device would not have to explode either to cause pandemonium at the Winter Games.

In 2004, the president of Chechnya was assassinated by a bomb blast while attending a Victory Day ceremony celebrating the Soviet defeat of the Nazis in World War II. The explosive device had apparently been built into the reviewing stand long before the event, possibly when the stadium was undergoing repairs. This, too, was inventive compared to the usual suicide bomber armed with dynamite, shrapnel and the readiness to die.

Two bombings of that sort in Volgograd in late December — one in the main train station, the other on a municipal bus — nevertheless sent ripples of fear across Russia. The number of people attending New Year's Eve festivities in Moscow was down by 50 percent. About 50,000 people turned out and were watched over by 5,000 police.

The history of relations between Russia and the peoples of the North Caucasus, especially Chechnya, is long and tangled. Some historians date the initial clash between Russia and Chechnya to the time of Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century, while others date the conflict to the period of Catherine the Great at the end of that century. In any case, the grievances are many and the memories long, with the victims always having longer memories than the victors.

Among all the traumas and atrocities, one stands out. In early 1944, on Josef Stalin's direct orders, the entire Chechen and Ingush nations — every man, woman and child were rounded up, packed into cattle cars and exiled to Kazakhstan. Those unfit to travel were herded into buildings that were then set on fire or were machine-gunned. Something like a quarter or a third of those exiled died en route or in the first harsh years. Some have termed this attempted genocide.

Stalin accused the Chechens and Ingush of aiding the Nazis. Some did support the Nazis, as did many Ukrainians and Russians for that matter, but for the most part Chechens and Ingush fought bravely for their Soviet homeland.

Many of today's Chechen and Ingush leaders grew up in exile. For them, Stalin's crime against their nation is not just historical memory but personal experience. And so many people of the North Caucasus bear bitter grievance against Moscow, regardless of whether they have separatist or Islamist values. The specific objects of their wrath are Stalin, the KGB, which carried out the deportations, and the glorification of the Soviet victory in World War II.

Terrorists choose targets for a variety of reasons — convenience, maximum impact, publicity — but the symbolic aspect should never be discounted.

Three recent bombings took place in Volgograd, formerly Stalingrad and site of the battle that turned the tide against the Nazi invaders. Izmailovo Park where the first radiological dirty bomb was planted, used to be known as Stalin Park. The explosives built into the receiving stand in Grozny were detonated during a May 9 Victory Day celebration. One of the worst suicide bombings took place in Moscow's Lubyanka Metro station right by the old KGB headquarters. Not every act of terrorism in Russia has symbolic resonance, but a great many do.

For that reason, it is astonishing that Feb. 23 has been chosen as the date for the concluding ceremonies of the Sochi Winter Olympic Games. That was the very day in 1944 when the Chechens, Ingush and other ethnic groups were rounded up for deportation, a task made all the easier because it was Soviet Army and Navy Day, and people were expected to assemble in public places. Now renamed Defenders of the Fatherland Day, it is still celebrated on Feb. 23. For the peoples of the North Caucasus, this is a date that lives in infamy.

Doku Umarov, leader of the Islamist insurgents and called the Osama bin Laden of Russia with even the U.S. State Department offering up to $5 million for his capture, has called for "maximum force" to be used against the Sochi Games. He considers the games a sacrilege, a "Satanic dance on the bones of our ancestors." To schedule the concluding ceremonies on the day that marks the 70th anniversary of the deportation only adds insult to injury. That choice was either an act of colossal ignorance or colossal arrogance. What is sure, though, is that the Chechens remember and so do the other deported peoples.

If the Islamic insurgents are indeed planning on using drones or UAVs to ruin Russia's Olympics, they may save them for the concluding ceremonies so that the Russians, too, may never forget Feb. 23.

Richard Lourie is the author of "The Autobiography of Joseph Stalin" and "Sakharov: A Biography."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.