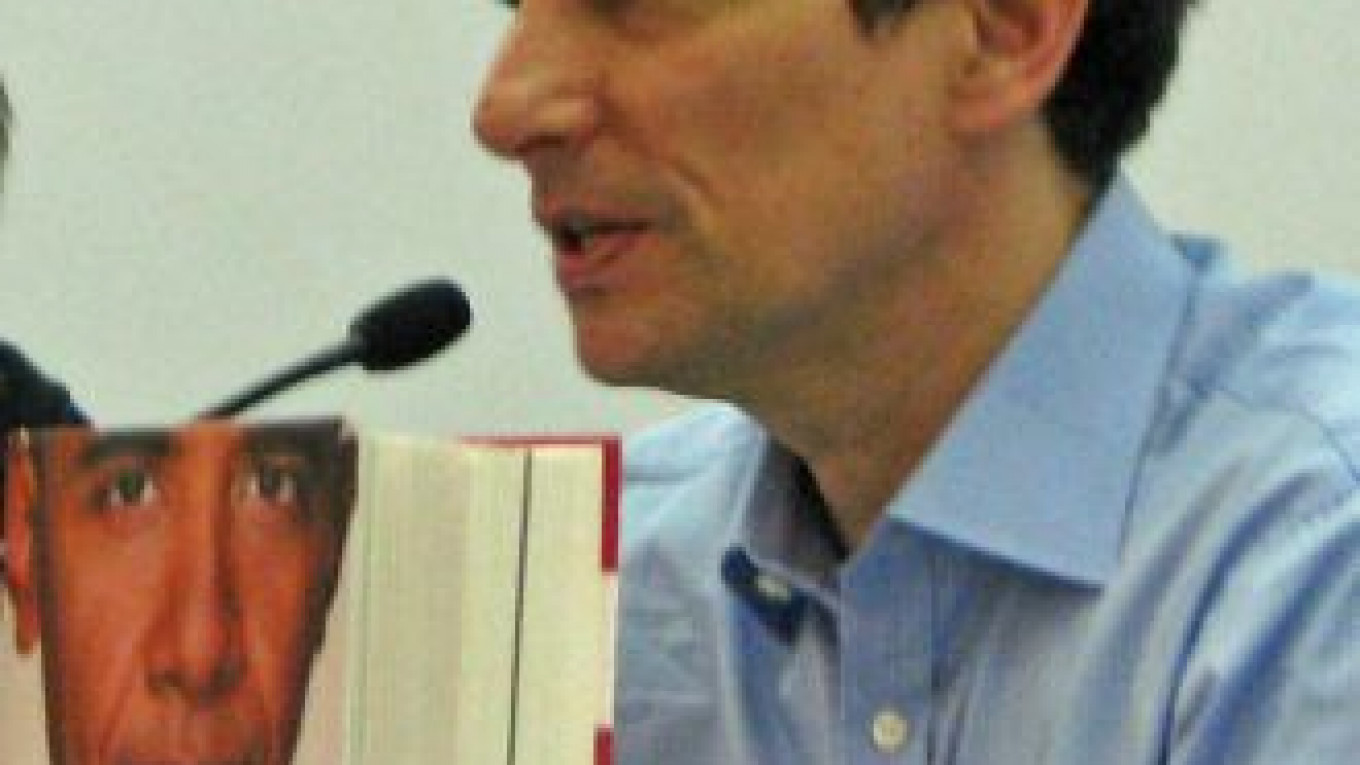

David Remnick says he has been lucky — "preposterously lucky" — twice in his professional life: once when he was posted to Moscow in 1988 as a correspondent for The Washington Post and once when he was made editor of The New Yorker magazine. But luck alone doesn't explain Remnick's professional success. This prolific writer and Russia-watcher has written thousands of articles, won dozens of awards, and is the author of six books, including "Lenin's Tomb," which received both the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction and a George Polk Award for excellence in journalism. His most recent book, "The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama," has just come out in Russian translation. He was recently in Moscow to present his book, immerse himself again in the Russian language, and return to a stint of reporting. Before he wrote up his impressions for The New Yorker, he found time to talk with Moscow Times columnist Michele A. Berdy about Moscow "then" and "now," the disparate joys of reporting and editing and the yin and yang of Russian politics.

Q: Are you used to the changes in Moscow or is it still a shock when you arrive?

A: The commercial stuff I'm used to. That's been around for a long time now. But there's always someone to visit, someone to see, something to hear about that really is mind-altering on the cultural or political level. I had never been to the Red October Chocolate Factory, which was kind of a breakthrough place — it had a political meaning even in the 1990s when it was one of the first privatized companies. Now there's Dozhd (an Internet TV station), Bolshoi Gorod — young people running around with great energy and doing their thing.

Q: When you were reporting here the Soviet Union was breaking up, and now …

A: It's hard not to be crushed when you think about the overall shape of the political system. It's hardly what anyone imagined in 1990-91. But that was a very long time ago. … Today people talk about it being a kind of analog to the Brezhnev era, which is to say stagnant, repressive politics, an oil rich mono-economy. … But it's not the Soviet system. The Soviet system was absolutely comprehensive and absolutely repressive. The key word was "absolute." This is a much cleverer system. It allows much more to happen. It allows steam to be let off. The question is how much steam…

It's clear — and not just in Moscow circles; you can sense it in the regions, in corners of the Internet — there is a lot of dissatisfaction with the recent рокировка (job swap). It was a quantum leap in cynical just to casually say, "We thought of this years ago and it was all decided."

But I think circumstances are so radically different now. There were signs of civic life before 1985 — mainly the dissident movement — but they were really isolated and really repressed. And then there was a revolution that had to be initiated from above by an extremely daring reformer and eventually by his even more radical antagonist. Gorbachev and Yeltsin were a kind of yin and yang. That's clearly not the case now. The yin and the yang at the top of the system now are not antagonistic — they lead the same system. And the key word of the system today is продолжение (continuation). Gorbachev's line was так жить нельзя (we can't live like this) but now it's the opposite: надо так жить и дальше (we have to continue to live like this in the future, too).

Q: Do you think that coverage of Russia in the United States is too much, not enough, about right?

A: I couldn't do a Three Bears thing on it. The amount of it is never going to be as much as when I was here because then it was just event after event after event. … One could have written three or four articles a day, and sometimes I did. Yes, there's less of it in the mainstream media. There's no question about that. And interest is lower. But we're obsessed with other things.

Q: Do you miss being a reporter on the ground?

A: Sure, but I can only live one life. Which is why — I hope not to the despair of my wife — my version of going to the beach is to go some place for a couple of weeks with a notebook. I get more out of it. If you go to the beach, you get a sunburn that begins to peel. If you report, you learn something. Although an editor and a reporter seem to be joined at the hip, they are very different. As editor of The New Yorker, I'm largely enabling other people's creative and journalistic work in order to get it to where they want it to be. But being a writer or reporter — it's your thing entirely. It's much more focused. We do have some great writers and with them my sole function is to say "thank you." I mean what would I say to John Updike when he sent me an essay other than "Thank you, this is even more amazing than the last one"?

Q: Do you like being an editor?

A: I do! I bet I'd like playing second base for the Yankees and being the China correspondent for The New York Times, too, but you have to choose.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.