Europe's outgoing human rights chief has some advice for the Latvian national who will succeed him: travel to Russia often to win the respect of local officials and press them hard to fulfill their promises.

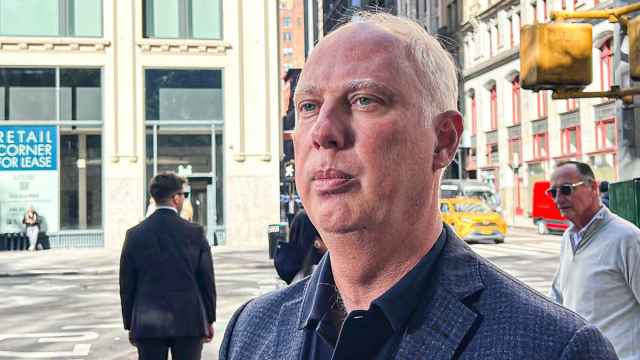

Thomas Hammarberg, the Council of Europe's human rights commissioner, lamented in an interview that Russia's human rights situation has not improved much over his six years in office.

"The situation is not dramatically different from what it was when I arrived," he said by telephone from Strasbourg.

On April 1, he will pass the torch to Nils Muiznieks, who was elected as his successor by the Council of Europe's Parliamentary Assembly late Tuesday. Muiznieks, a former Latvian minister, has served as a member of the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance since 2005 and as its chairman for the past two years.

Hammarberg, speaking a day before the vote, said his successor should travel as much as possible "to remain in touch with reality" and earn respect from member countries' key officials.

"If you keep sitting in Strasbourg reading newspapers, you cannot really give good advice," he said.

He said he visited Russia almost 20 times, making the country his most frequent destination behind Turkey. But he also said those two countries were by no means alone in getting his attention, noting that he spent a lot of time last year on Britain's treatment of Roma travelers and many Western European countries' migration policies.

On Russia, Hammarberg said small improvements in recent years could not compensate for the authorities' widespread inaction on human rights.

As positive examples, he cited the fact that most regions now have ombudsmen — some of whom are "quite active and competent" — and have eased the process for citizens to file complaints.

But he said the most pressing problems remain in the North Caucasus, where abductions and regional officials' impunity are top concerns. The mainly Muslim region is plagued with terrorism and regular clashes between Islamist insurgents and security forces.

"We feel that further action must be taken to ensure that counterterrorist actions are in line with human rights standards," he said.

The North Caucasus features prominently in Hammarberg's last on Russia, issued last fall.

Hammarberg said talks with law enforcement officials, including Investigative Committee chief Alexander Bastrykin, have yielded promises but few results.

Bastrykin last year promised to press investigations into the murders of Novaya Gazeta journalist Anna Politkovskaya and Chechen human rights activist Natalya Estemirova after meeting with members of the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists.

But Hammarberg said progress was disappointingly slow. "They really need to put more energy into the investigations," he said.

Moscow has ratified more than 50 European conventions committing it to protect human rights since Russia joined the Council of Europe in 1996. But critics say these commitments remain largely on paper.

Most prominently, the State Duma has for years blocked a crucial reform of the European Court of Human Rights, which is the council's strongest instrument in forcing members to comply with standards spelled out in the European Human Rights Convention. The Duma gave up its four-year blockade only in January 2010, a move credited by many to President Dmitry Medvedev. The reform significantly speeds up the admission process to the Strasbourg-based court, which has suffered from an overload of cases.

Hammarberg said judges' workload remains a problem, pointing out that the court recently received some 8,000 complaints alone about controversial reforms in Hungary that have been criticized as a rollback of democracy.

Russia has in past years provided the bulk of the court's complaints, producing a flood of more than 40,000, or 29 percent of the total, from 2002 to 2010. Moscow has lost some 90 percent of the cases that the court decided to hear. Most of them stem from the armed conflict in Chechnya.

Hammarberg said that while the government has always paid compensations as required, it has done little to punish those responsible. "Most of the problems are related to the investigations," he said.

Regarded as Europe's most high-profile human rights official, the Council of Europe's commissioner serves a nonrenewable six-year term. But the office has no executive powers apart from investigating rights violations and publishing recommendations.

Hammarberg, 70, said he plans to retire to his native Sweden and write a book about problems with democracy in Europe. Among the real problems, he said, are how governments can manipulate the media and the difficulties opposition groups face in attaining government office.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.