There was the moment when Baldori played a lovely, laid-back version of "The Tennessee Waltz." As he played, I was thinking, "This is a great interpretation of 'Sittin' on Top of the World.'"

I would like to think my mistake was forgivable. As Baldori pointed out from the stage, "Tennessee Waltz" goes back to the blues and jazz and country traditions all at once. It's one of those songs that have morphed into almost everything possible over the decades, including "Sittin' on Top of the World." Or is it the other way around? And then there was the moment when, with Schmitt playing some blistering piano, Baldori leaned meanly into his harmonica and began belting out "Help Me," the old Sonny Boy Williamson barn burner.

The first time I ever heard "Help Me" was when Van Morrison played it at a series of concerts I attended at the Troubador club and the Santa Monica Civic concert hall in the Los Angeles area in 1972. I was just a dumb teenager, sopping wet behind the ears, and I was thrilled to hear a new Van Morrison song I didn't know.

However, knowledge, if not wisdom, comes quickly enough if you're open to it. And it wasn't long before I learned that "Help Me" came out of the great Chicago blues and r&b stewpot. Just as I came to know that other songs Van sang that night &mdash "Ain't Nothing You Can Do" and "I Believe to My Soul" among them &mdash went back to the Bobby "Blue" Bland and Ray Charles songbooks, respectively.

On those nights Van Morrison did a huge favor for a green kid who thought that music began and ended with rock 'n' roll. All of a sudden there was blues. And there was soul. And there was jazz. And there was country. And there were entire universes in between each of those planets. A whole roiling tradition began pulling me in. American music &mdash even when interpreted by the Irish genius Van Morrison &mdash sucked me in from my head to my toes.

I am often asked how I, born and raised in the Mojave Desert, came to live in Russia and write about theater. Bob Baldori asked me that as we sat having post-concert drinks in the Forte Club just off of Pushkin Square. I told him what I always say: Theater in Russia is the equivalent of music in America. I grew up in the United States deeply distrustful of theater because it was so often cheap, superficial and obvious. But music &mdash now that was something else. I grew up loving all the various musical traditions that America threw at me every day and every hour, even if I had no idea where they were coming from. I still remember sitting out on the back porch of my parents' house in the desert and hearing Chuck Berry burst into my transistor radio for the first time with his brand new hit "School Days." It scared the hell out of me. There was something incredibly menacing in it. This guy was taking me someplace else. It was the truth I heard in the music, the honesty that grabbed and held me.

Cut to Moscow &mdash where pop music must be one of the seven blights of the world. Don't get me started on Russian pop. Never were deader, phonier notes ever sung or played. Ah, but the theater of Kama Ginkas! Pyotr Fomenko! Lev Dodin! As I started going from theater to theater, from revelation to revelation, I began making unexpected connections. The theater of Kama Ginkas mysteriously but profoundly reminded me of Bob Dylan's music. Pyotr Fomenko &mdash of maybe Al Green, or of Miles Davis in his "cool" period. The comparisons aren't important &mdash the fact that they arose is. This was a world I recognized instinctively and wanted to know better. Russian theater reached down inside me and turned me around like Dylan did, like Etta James did, like everybody from Gene Vincent and Johnny Cash to Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen did. Drop by the Satirikon Theater some day and watch the great actor Konstantin Raikin at work on stage. If you know the immortal records of Big Mama Thornton, you just may see the connections I do.

It was here in Russia that I made the discovery: American theater is dangerously similar to Russian pop music. But Russian theater &mdash that comes from the same place that American music comes from.

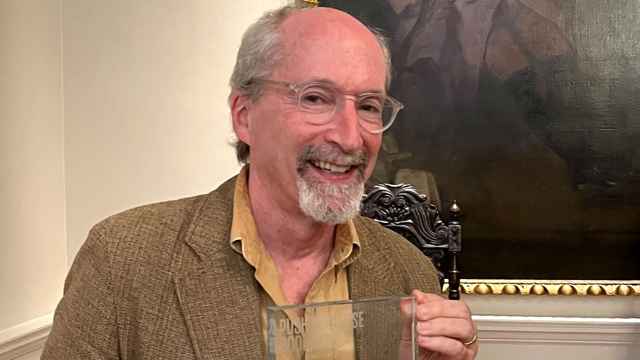

So, I'm sitting with Bob Baldori in a Moscow jazz club talking about my life in theater and his in music. You see, Bob Baldori has played piano with and for Chuck Berry since 1966. He played with Bo Diddley. He played with Muddy Waters. And Bob is telling me how you make music that is not just good but really good. It's the beat. The backbeat. "You've got to hit that groove and hold it," he said. Bo Diddley was especially good at teaching that, he said. And I'm thinking, "Yeah, Raikin and Dodin and Ginkas &mdash they do that, too."

For the same reason I'll get in a car and travel around following Bob Dylan or Van Morrison from concert to concert for a couple of days in a row, I will also get on a plane or a train and travel around Russia to see what kind of theater people are making in Yekaterinburg or Togliatti or St. Petersburg or Belgorod. Amazing what you'll do to watch someone hit a groove and hold it.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.