The last thing that Russia’s tentative economic recovery needs is for the country’s banking sector to trip it up. Loan growth is flat in 2010 so far, and if banks don’t start lending soon, the economy may continue to struggle to grow as cash-starved companies hold off on investment and consumers defer purchases. ?

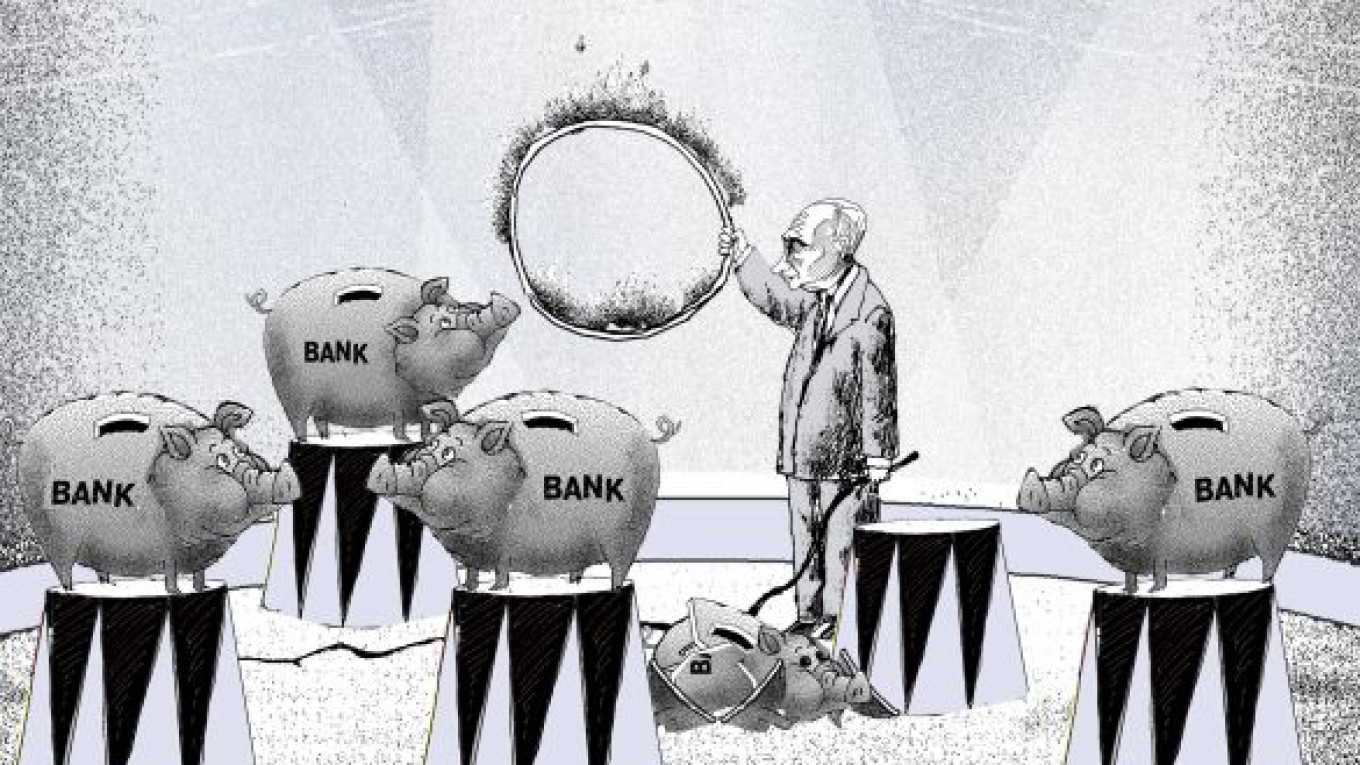

So when Prime Minister Vladimir Putin forecast in front of the State Duma on April 20 that Russia’s banks would increase lending by as much as 10 percent this year, it wasn’t just an idle prediction. It was a fervent wish, firm order and threat all rolled into one.

The good news is that the Russian banking sector made it through the economic crisis even after it was hit by the powerful double whammy of plummeting commodities prices and the global credit crunch. The Central Bank floated the sector on an ocean of cheap cash and quietly and quickly tackled potential sources of systemic risk.

But while the banking sector has lived to see another day, it hasn’t done any favors for potential borrowers or for the economy as a whole. ?

Banks and borrowers are finding themselves in a real conundrum. Banks are understandably hesitant to lend to potentially dodgy borrowers in what is still an uncertain economic environment. They don’t want to add to the mountain of bad loans that has increased nearly fourfold to 6.4 percent of total loans by the end of February, according to Russian accounting standards. Therefore, to be compensated for what they perceive as continued high levels of risk, banks are demanding interest rates that are higher than what potential borrowers can afford.

Until there’s a higher level of confidence among banks and in the economy as a whole, neither banks nor borrowers want to take the first step. Continued high unemployment and slow wage growth is dampening demand for retail loans, which account for just over one-fifth of the total $525 billion in outstanding loans in the country’s banking sector. In the meantime, banks are building up cash cushions and plowing their liquidity into domestic bonds.

What should we do to escape the vicious circle? Borrowing costs have declined. The refinancing rate, an indirect but key determinant of lending rates, has been cut by 500 basis points over the past year, and it reached a historic low of 8 percent on Friday. In theory, this should inspire more borrowers to take the dive. Some may be waiting for a sign that rates have bottomed, but banks don’t often pass these types of cuts on to borrowers.

The government has long been trying to get banks to boost lending. Indeed, the string of rate cuts was kicked off last spring the day after Putin suggested that Central Bank head Sergei Ignatyev consider cutting rates. A few months later, Putin called on the heads of state banks to defer their vacation plans until they increased lending.

More recently, on April 8, the Central Bank announced that it would continue its crisis-driven policy of not requiring banks to increase provisions for restructured loans. The continuation of a liberal provisioning policy flies in the face of global standard industry practices and bodes ill for upgrading regulation later. Most tellingly, in mid-April Sberbank head German Gref — immediately after meeting with Putin — announced an across-the-board cut in rates for loans to retail customers and a reduction in commissions and fees, which will likely hit the bank’s profitability. Since Sberbank accounts for close to one-third of total loans outstanding, other banks will be forced to follow its example or else face sharp deterioration in market share.

The government’s role in the Russian banking sector is already outsized. Research by economist Andrei Vernikov for the Bank of Finland shows that the percentage of banking sector assets controlled by the state has risen from 36 percent in 2001 to 56 percent by mid-2009. Instead of embracing a free-market model for the banking sector, like most other former Soviet republics have done, Russia has been drifting toward the Chinese model of state control of leading banks. Any increased government involvement in the nuts and bolts of bank lending will accelerate this trend.

Is state control over the banking sector such a bad thing? Arguably, state control makes it easier for the government to support banks, which could reduce the likelihood of instability that could be a trigger of future banking crises. But at the same time, an increased government role in the banking sector produces dangerous distortions in the market. Private banks and private investment are the first victims. Increased levels of directed and politically influenced lending are an obvious consequence, invariably leading to higher levels of nonperforming loans and massive government-funded recapitalizations of floundering banks.

In addition, state banks may be forced to support politically motivated projects. The ambitious attempt last year by Sberbank to acquire a large stake in Opel was a good example. The inefficient allocation of capital and the slow but steady crowding out of private capital undercuts healthy and productive market impulses.

In the end, when the government increases its intervention in the banking sector, the largest victim is the country’s sustainable economic growth.

Kim Iskyan is a director at Eurasia Group, a ?political risk consulting firm based in Washington.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.