Has Russia’s economic crisis ended? That depends on whom you ask. Ask Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, or any official of his United Russia party, and you will be told, “Of course it is over.” They will even produce proof in the form of an unemployment rate that does not rise, unprecedented increases in pensions and strong growth in construction and metalworking.

Of course, all these comparisons are made with how things stood last month rather than with the country’s precrisis economic performance. Then there is another “miracle” that the government is starting to trumpet, one discovered in August 2009: an increase in Russia’s population. Unfortunately, in no month before or since have births outpaced deaths.

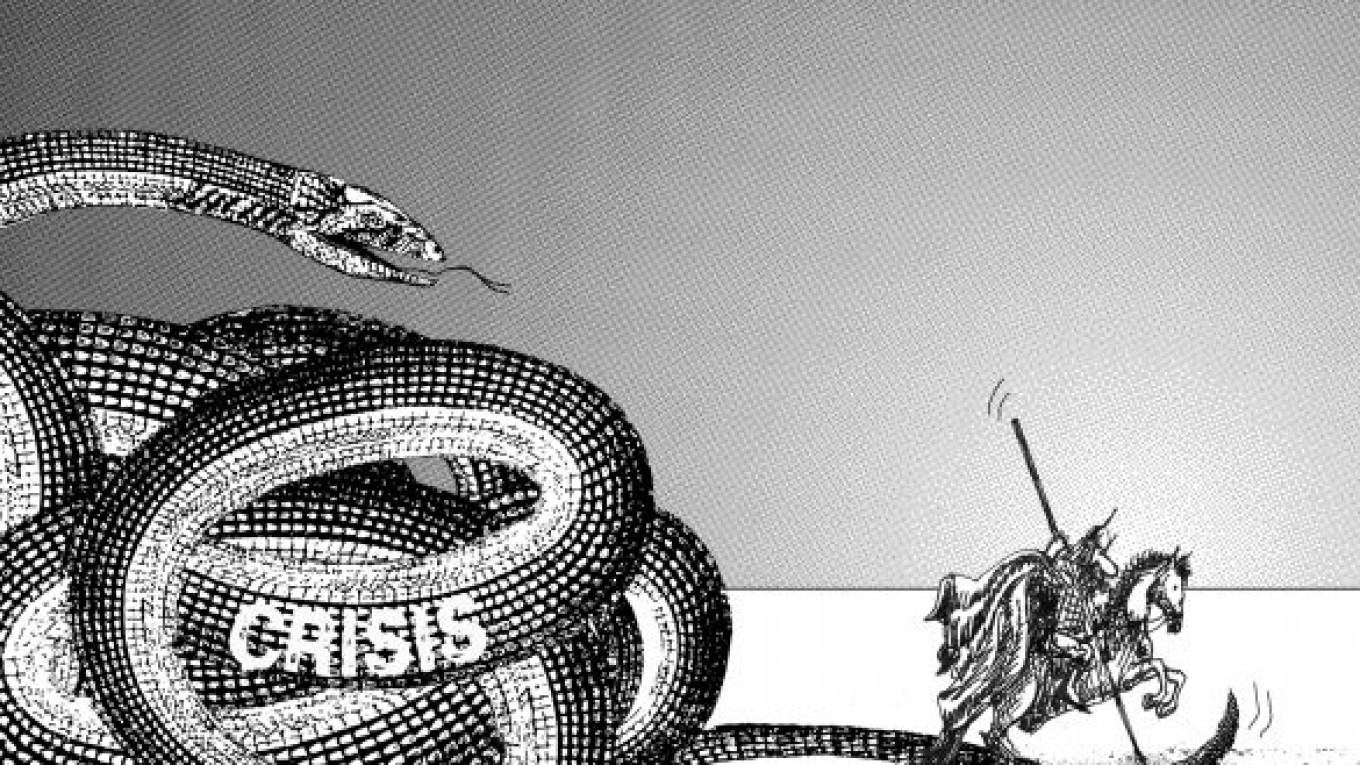

Ask a member of the opposition whether the crisis has ended, and you will be told that it is only just beginning. Gazprom’s production is falling at a dizzying pace, and the country’s single-industry “mono-towns” are dying.

There is truth in both views about the state of Russia’s economy, but because the government controls all the major television channels, it is succeeding in enforcing its view of the situation. Indeed, the opposition has access only to a few newspapers and radio stations, leaving the Internet as the sole remaining space of freedom in Russia. But there you can read very pessimistic estimates of the country’s economic future. So the Kremlin blinds its citizens with rosy scenarios, while the Internet overdramatizes reality.

The truth, it is clear, is somewhere in the middle. What is beyond dispute is that Russia’s economic health depends on external factors. But, outside Russia, no responsible economists can even begin to say whether the crisis is truly over. They know that relatively calm markets do not mean that strong economic growth is around the corner.

Russia’s economy is now hostage to potential global growth. It is clear why: The state budget depends almost totally on energy prices. Now that the oil price has reached $80 per barrel, the Central Bank can start buying foreign currency again. Gold and foreign currency reserves are increasing, implying appreciation of the ruble. But Russia’s budget for 2010 is still headed for a serious deficit because of high government spending.

The rapid income growth of the early Putin years is a thing of the past. While it persisted, expenditures swelled but were manageable — until energy prices collapsed suddenly. The Kremlin, devoted to its key fetish — Putin’s approval ratings — proved completely unprepared to curtail public spending in the wake of falling state revenues. Unsurprisingly, the budget deficit ballooned.

Yegor Gaidar, Russia’s first pro-reform prime minister, warned the government about the consequences of inflated oil prices, repeatedly arguing that excessive spending growth would undermine the political will for retrenchment when it became necessary. Gaidar died in December, his unheeded warnings having come true, proving once again that no man is ever a successful prophet in his own country.

In recent months, the government finally brought inflation down to 8 percent. Sometimes this is presented as another milestone demonstrating that the crisis is near its end. But that is wrong. Inflation fell as a result of the crisis, which reversed the direction of capital flows. Whereas inward investment reached $20 billion in 2008, capital outflows totaled $20 billion in 2009. The Central Bank buys less foreign currency and, thus, issues fewer rubles, reducing inflation.

A far more inertial indicator is unemployment, which experts predict will grow in 2010. The problem is that the country’s labor is less mobile than in the Europe and the United States. Russians prefer lower wages — or simply waiting with no wages at all — to moving in search of a new job.

The situation at carmaker AvtoVAZ is a striking example. Last year, output fell to 300,000 cars, from 800,000 in 2008. Such a dramatic fall in sales would normally require massive layoffs or lower wages. Yet of the company’s 102,000 employees, only 27 favored layoffs. As a result, wages were cut by half. The state, which is seeking to rescue the domestic automobile industry, allocated to the firm more credits through state-owned banks.

But how long can such a situation last? One day, it will no longer be possible to disguise unemployment through shorter working weeks, forced leaves of absence and decreases in wages. When that happens — and there is a strong probability that it will happen next year — the crisis will only be just beginning for Russia.

All over the world — particularly in the United States, Europe, and China — stimulus programs have paid off, as expected. But it is not yet certain whether the engine of the global economy will be able to run without additional liquidity, possibly undermining fiscal stability worldwide. Elsewhere, that will become clear in the first half of 2010. In Russia, signs of recovery, if they appear at all, will lag well behind the rest of the world.

Irina Yasina is an analyst at the Institute of Transitional Economy, a weekly economic commentator for RIA-Novosti and a representative of the Open Russia Foundation. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.