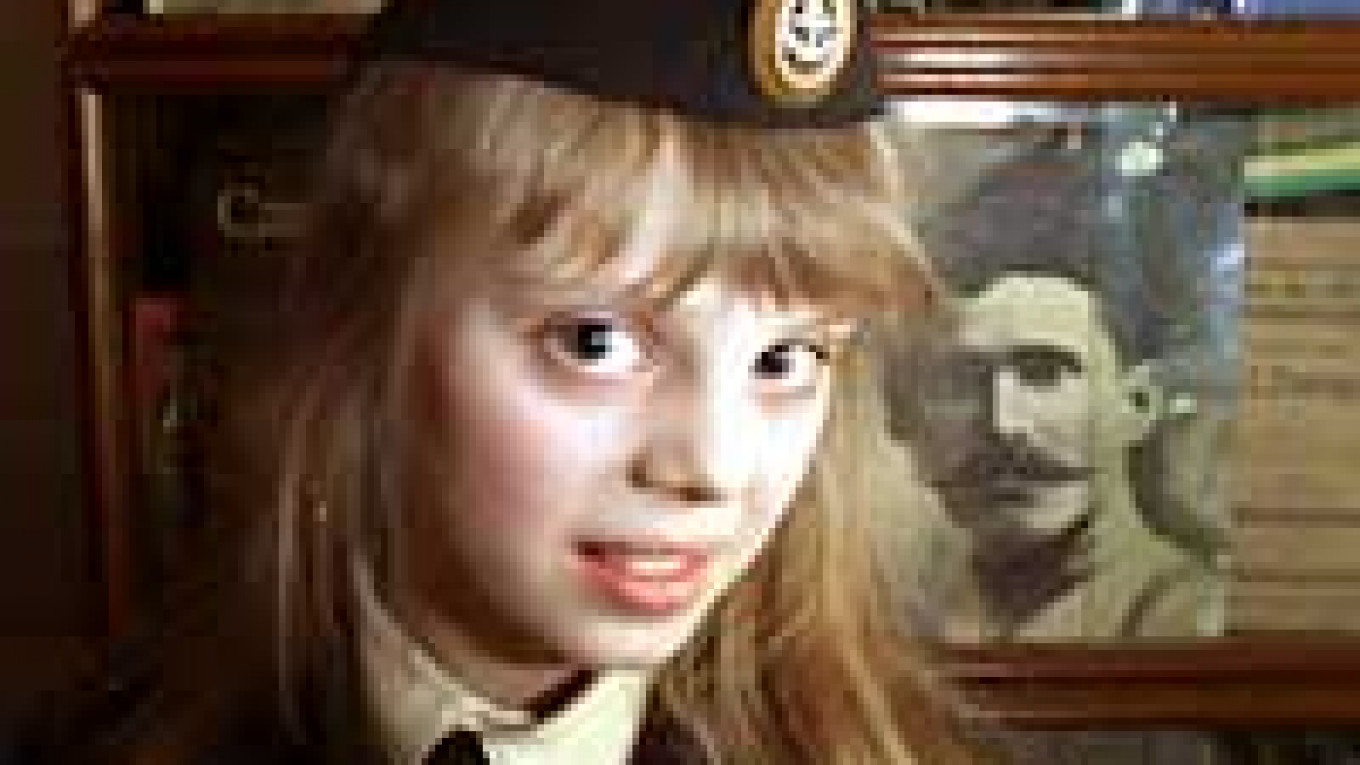

"It's hard sometimes to live up to Vasily Ivanovich. But I feel I'm the one to carry on the family's honor," the thin, fair-haired Vasilisa said in a recent interview in her family's tiny three-room wooden house outside of Moscow.

Young as she is, little Vasilisa is not only eager to keep the Soviet hero's memory alive, but ?€” to some extent ?€” to follow in her great ancestor's footsteps: She plans to become a military interpreter and has just begun studying Japanese.

Vasily Chapayev was born in 1887, in a rural settlement that is now part of the capital of Chuvashia, Cheboksary, a Volga city some 600 kilometers east of Moscow. A son of peasants, he was conscripted into the tsarist army in 1914 at the start of World War I. Although he was awarded three St. George's crosses for valor while fighting with the imperial army, true fame came to Chapayev after he threw his support behind the Revolution and became a legendary commander battling the White army in the Urals. In 1919, a wounded Chapayev was shot and drowned in the Ural river ?€” a scene immortalized in film and fiction.

Legends about Chapayev have outlived their subject by decades. A 1934 feature film called "Chapayev" became immensely popular and, shortly thereafter, Chapayev became a fixture of every schoolbook, a key figure in Soviet propaganda and the prominent hero of hundreds of jokes. In the 1950s, Chapayev's name was conferred onto a new brand of chocolate-covered zefir, a favorite, marshmallow-like Russian sweet. The candies eventually came to be sold in a specially designed tin adorned with Chapayev's portrait ?€” one of which Vasilisa's mother gingerly lifted from a suitcase full of Chapayev memorabilia.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Chapayev's name became more and more removed from day-to-day life. But not for the family of Vasilisa Chapayeva.

The long-awaited only child of her parents Yevgenia Chapayeva and Viktor Pecherin, Vasilisa inherited her great-great-grandfather's name while still in her mother's womb.

"It was not even an issue whose surname Vasilisa would get," Percherin said.

There were no questions about her first name either, his wife Yevgenia chimed in.

"I asked for special permission [from the government] to give birth in Chuvashia ?€“ Vasily Ivanovich's homeland," said Chapayeva, a Muscovite by birth. "I got permission, but on one condition ?€“ if the baby was a boy, his name would be Vasily, and for a girl there were no alternatives but Vasilisa" ?€” an anachronistic, old-fashioned "female" counterpart to the name Vasily.

According to both parents, the most resilient keeper of the family flame was Vasilisa's great-grandmother, Klavdia Chapayeva ?€“ Chapayev's daughter, who was born in 1913 and died last year.

One of three children, Klavdia had lived in Moscow since the 1930s and spent her life as a passionate collector and preserver of all things pertaining to her father's memory. Klavdia Chapayeva had met dozens of the highest-ranking Soviet officials, including Kremlin mainstay Anastas Mikoyan and former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Although Klavdia had two brothers, it has traditionally fallen to the women in the Chapayev family to pass the renowned name down the line.

When Yevgenia became pregnant she quit her job at a small factory that made Soviet souvenirs for top Communist Party officials.

"I wanted this child so badly that I decided I would devote my life to raising her, to making her a smart, gifted kid," Yevgenia said.

"This is all for Vasilisa," she added, pointing to the snow-covered trees outside. "I want her to breathe fresh air and enjoy the closeness to nature."

But the abundance of fresh air for the Red Commander's heiress comes at a price. With Vasilisa's yen for the armed forces, she studies at a special naval academy in northwest Moscow; to be there on time, Vasilisa and her father wake up at 5 a.m. every morning to make the two-hour trip to the school.

To accommodate this schedule, Vasilisa's father quit his job as a theater set designer and switched to doing odd jobs and maintenance work at the academy.

But the sacrifices and inconveniences haven't fazed Vasilisa's parents, who seem content to give up everything for the sake of their only daughter.

At her school, which typically admits children aged 10 or 11, Vasilisa is the youngest student. In order to be accepted, she skipped a grade at her previous school by fulfilling all the requirements for that year in just one month. Teachers never tire of praising her.

On Wednesday, Vasilisa was awarded the title of "Brave Tin Soldier," a citywide award ?€” named after Hans Christian Andersen's touching fairytale ?€” given to kids who show exceptional qualities in getting along with and helping their peers.

"She became enthralled with the armed forces after we went to a reception hosted by Chuvashia's representative in Moscow, where a lot of members of Russia's top military command were present," Yevgenia recalled. "And when she saw all those men in uniform she couldn't think of anything but a military career!"

Vasilisa is very keen about her future occupation.

"I really want to work as an interpreter. I think I can be very useful."

Perhaps not surprisingly, her mother does not object.

"I really don't see anything bad about it. Somebody has to serve the country ?€” so why not my daughter?"

Commander Chapayev's life story, while distant history to many of her classmates, is a part of Vasilisa's daily life.

"I've been listening to family stories all my life," the 9-year-old said. "One day I will be the one to carry them on."

At her tender age, Vasilisa is quite a celebrity in her own right. Along with their Chapayev-related archives, her parents have folders stuffed with press clippings about their little girl.

"Look: This is how much attention she got from the press when she was born," her father said, hoisting up a fat stack of newspapers articles.

Vasilisa takes the publicity with a stoic calmness.

"I've watched my great-grandmother and my mother talking to the press, and I think it's my duty to do that too," Vasilisa said in an unexpectedly grown-up manner. "I especially felt it after my great-grandmother died."

Her fellow cadets have been excited to hear Vasilisa's family tales.

"If I'm asked about it, I tell them," she said.

"But when someone tries to tell me a joke about my great-great-grandfather, I don't like it ?€” it hurts a little bit."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.