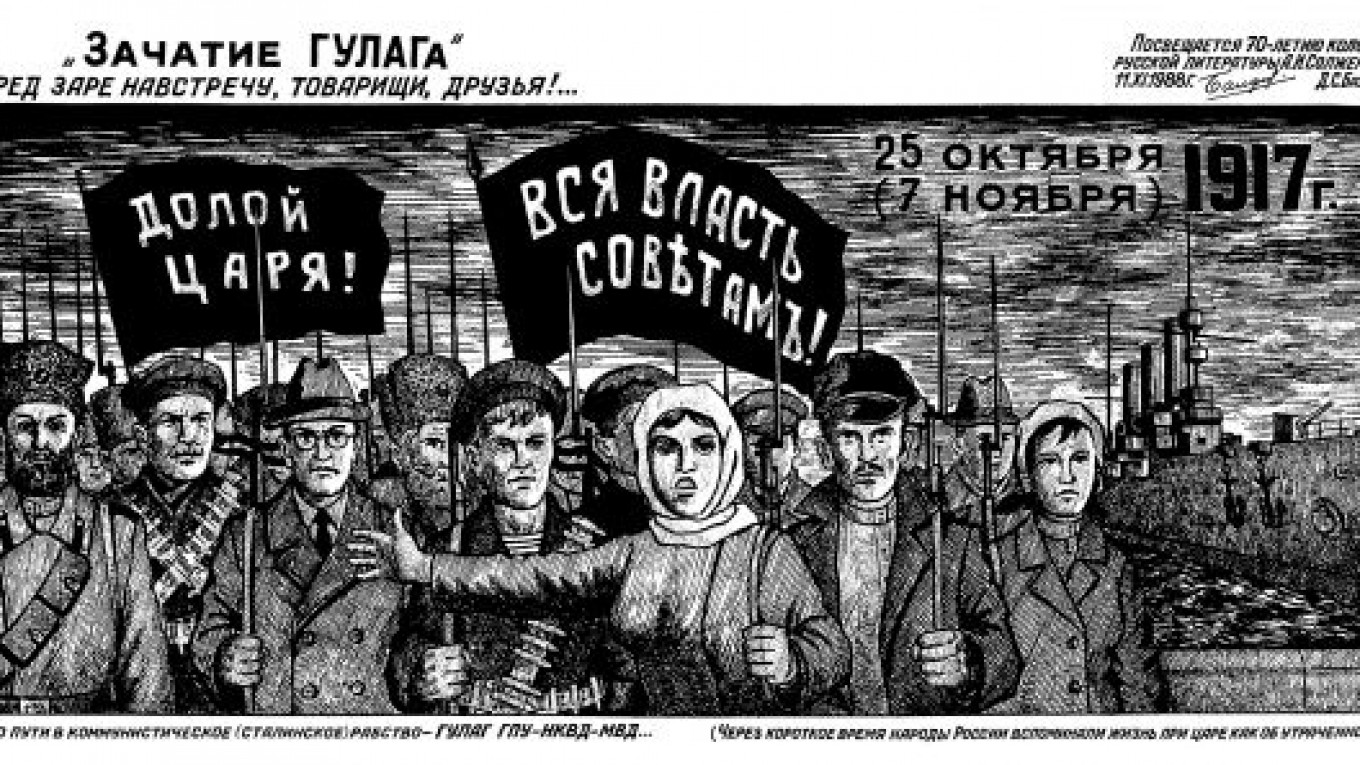

“Drawings From the Gulag” bears witness to some of the most horrific events to take place in Soviet prison camps, scenes that no camera was ever allowed to capture.

Almost 240 pages cover to cover, the book begins with a terse biography of author and illustrator Danzig Baldaev, a former warden at Leningrad’s infamous Kresty prison. After that, it’s basically 130 detailed depictions of beatings, rape and torture.

Baldaev, born in Ulan-Ude, Buryatia, in 1925, was the son of an “enemy of the people” — his father, an ethnographer, was arrested on charges of promoting tsarism — and he was raised in an orphanage for children of political prisoners. He fought in the Soviet army in World War II and, in 1949, was appointed to serve as a guard at Kresty, where he began keeping meticulous records of prisoners’ tattoos.

He reported his findings to the KGB, which, acknowledging that prisoners’ status and backgrounds were coded in their tattoos, sent Baldaev to penal settlements across the Soviet Union to continue his research. In those remote locations, he witnessed many of the shocking events recorded in “Drawings From the Gulag.”

“Initially [the drawings] appear overdramatic, focusing on the abject, the grotesque and the aberrant,” the book’s editors, Damon Murray and Stephen Sorrell, write in the prologue. “Perhaps because they aren’t photographs it is easier to dismiss them as a figment of a disturbed imagination.”

The images, and their accompanying descriptions, often overwhelm.

A man is prodded into a tiny “settling tank” that holds dozens of prisoners. Baldaev notes: “Without enough room or fresh air to breathe, some died, their corpses stood upright, squeezed in between other bodies.”

A two-page spread meticulously depicts the mass rape of female “enemies of the people” aboard a ship destined for a penal colony in far eastern Magadan. “Convicts entered the hold, breaking through the partition walls, with the collusion of the guards and crew,” Baldaev writes. “Those who tried to resist were stabbed to death or strangled.”

“Our reason for publishing the book was simple: These events are not as well-known as they should be,” Murray, the editor, said by e-mail. “We consider the work a historical document — we think of Baldaev’s tattoo drawings in the same way — and we felt an obligation to publish it.”

“By 1921, there were already 84 camps in 43 provinces designed to rehabilitate the first inmates who had been perceived by the authorities as enemies of the people. At any one time, there were about 2 million prisoners in the camps. Some 18 million passed through the system, a further 6 million were sent into exile. Although the camps shrank after the death of Stalin, many continued to operate, often less brutally, into the 1980s,” Murray said.

Fuel, the book’s London-based publisher, has also released the three-volume “Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopedia,” featuring a plethora of Baldaev’s renderings. “These books provide a way for us to expand readers’ knowledge of this subject, which is almost unknown in the West,” Murray said.

“Through these amazing and intricate tattoos, prisoners were able to tell details of each other’s deeds and misdeeds, specialities and even sexual preferences. The tattoos reveal the history of their bearers, a public record that can be read only by the initiated,” he said.

About a fifth of the illustrations in “Drawings From the Gulag” are from first-hand experience, the prologue concedes.

“We knew that Baldaev couldn’t have been present at all these events, they track almost the entire history of the gulag system. But we do know he had contact with people who were present at these events, both guards and inmates,” Murray said by e-mail.

“Because the authorities attempted to conceal its existence from the world, there are very few visual records of the gulag. Photographic records are scarce, usually limited to mug shots of inmates. Any broader photographic scenes were usually set up for propaganda purposes. They were sanitized and naturally devoid of truth.

“But where a photograph might capture the immediate reality, Baldaev’s drawings actually reveal more — they distill the essence of an experience into a vivid, focused scene. Very little is left to the imagination,” Murray said.

“They seem to reveal a side of him that recognized the then-largely untold atrocities committed by the regime, and they appeared to be his way of coming to terms with this — and perhaps his own complicity.”

“Drawings From the Gulag” is for sale on and .

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.