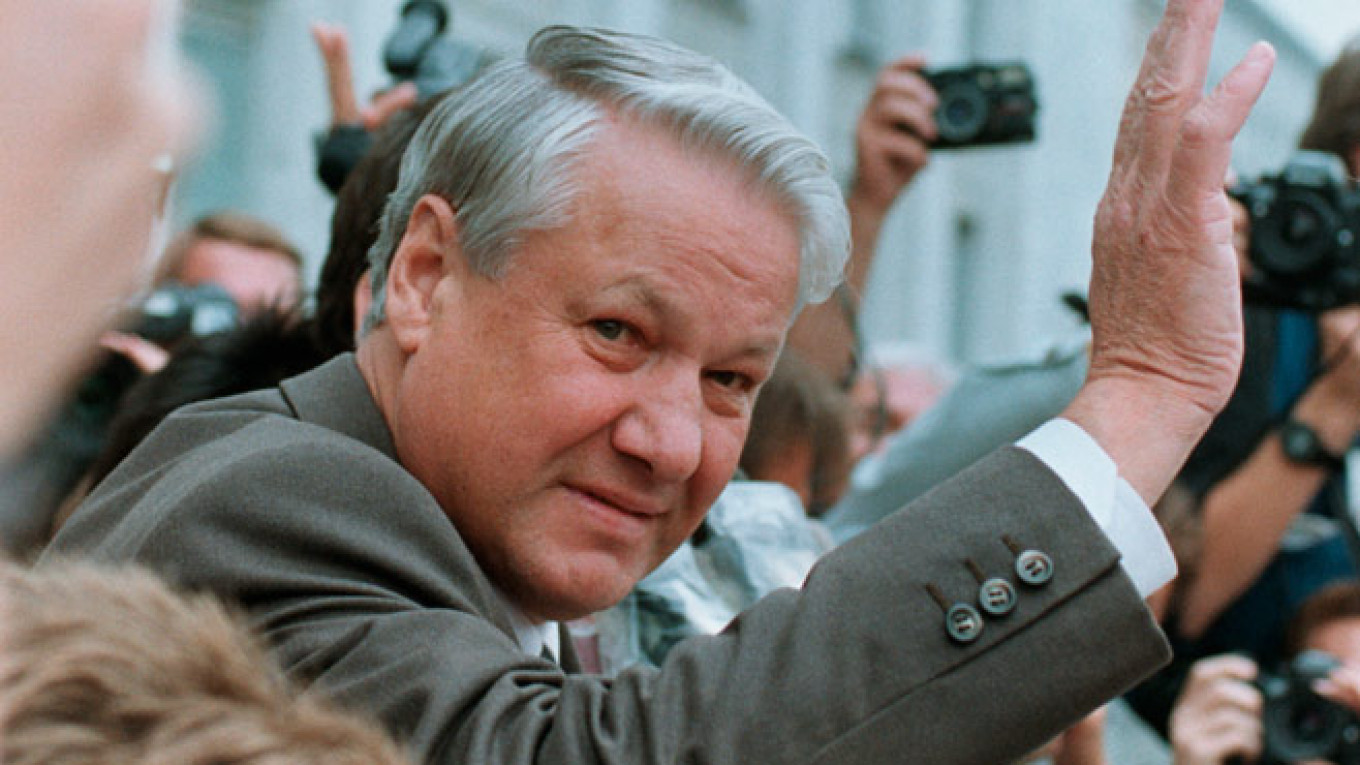

The opening of the center devoted to the legacy of Boris Yeltsin, Russia's first president, on Nov. 25 in the Urals city of Yekaterinburg, came on the heels of speculations surfacing among politicians that the notorious presidential elections of 1996, when Yeltsin won in the second round of voting, were conducted with violations and cannot be considered fair.

Just two months ago the former Kremlin official Oleg Morozov said in an interview with the Gazeta.ru news website that in the 1996 presidential elections — when Boris Yeltsin went neck and neck with the Communist candidate — were "solid evidence" that in the "wild '90s" the voting process could easily be manipulated.

He echoed the rumor that gripped public attention in 2012, when Russian opposition leaders claimed Dmitry Medvedev, then president, told them during a meeting that Yeltsin wasn't the actual winner of the 1996 elections. The statement was quickly refuted by President Medvedev's spokespeople.

"I categorically object to this point of view. The elections were absolutely fair," Naina Yeltsina, the first president's wife, said in an interview with the Gazeta.ru news website on Nov. 21. "It was impossible to falsify anything. We didn't know the results until the end. Anyone who has doubts can check with the elections protocols, it's all there," she said.

While doubts about the legitimacy of Yeltsin's win are yet to be settled, one thing is clear: In 1996 independent media during elections races were replaced with propaganda, said Ivan Kurilla, a historian and professor at the European University in St. Petersburg.

"It was then when we said good-bye to the independent journalism that turned into propaganda even on respectable television channels," he told The Moscow Times.

This is not the only controversial issue discussed nowadays in relation to Yeltsin's legacy.

Russian officialdom has continuously condemned Yeltsin's era, commonly called "the wild '90s," as a dark and unfortunate period of the country's history.

At the same time, Russian society doesn't have a univocal evaluation of the 1990s. For some, Yeltsin's years are associated with freedom — both political and economical — that Russia embraced after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and some remember this decade as the time when poverty thrived and criminality and corruption blossomed, blaming their forebears for everything that looks unfortunate today.

Nothing But the Facts

Founders of the Yeltsin Center, a historical and cultural institution, promise not to judge.

"[At the center] no one will impose any judgements or appraisals. Everything is designed in order to give visitors willing to reflect on the subject, especially those who doesn't know a lot about it, to see and feel how it was back then," Alexander Drozdov, director of the center, told The Moscow Times.

The center, 22,000 square meter large, includes a museum portion and several educational facilities for young visitors that will focus on different sciences. The museum portion is devoted to Russian history in general, from Novgorod princedom to the present day, though the history of the 1990s is exhibited in more detail, with, of course, Yeltsin as a focal point.

Part of the exhibition called "The Chechen Tragedy" is devoted to the Chechen wars of the late 1990s, one of the most controversial and harrowing episodes in Russian history. Representatives of the center said they were trying to make the exhibit honest and objective by including the Chechen wars in it. Another large part of it is devoted to the controversial elections of 1996.

The center was founded under a federal law that outlines creating legacy centers devoted to each Russian president at their places of birth and partially funded from the federal budget — according to Drozdov, the center was assigned 4.9 billion rubles ($75 million). Sergei Ivanov, head of the presidential administration, chairs its board, but Drozdov said no one from the Kremlin interfered with the center's work or content of the exhibitions.

Controversy Mounts

The official position about Yeltsin's era is quite clear nowadays. "A lot of my colleagues, presidents and prime ministers, told me that [at the time] they had already made up their minds that Russia, the way it was [at the time,] is about to end its existence," President Vladimir Putin said in the documentary "President," made by the state-owned VGTRK television holding in April, commenting on the state of the country in the 1990s.

Yeltsin, elected in 1991, aimed at transforming Russia's socialist economy into a capitalist market economy. In order to do that, he implemented economic shock therapy, price liberalization and nationwide privatization, which led to skyrocketing inflation rates and almost collapsed the country's economy.

His years in office are also overshadowed by painful military conflicts, including a clash with parliament in 1993 and two Chechen wars.

"The first public opposition activist, with unique experience gained in the Soviet Communist party, Yeltsin was a child of the Soviet totalitarian Communist empire," Gennady Burbulis, state secretary in 1991-92 and one of Yeltsin's closest allies, told The Moscow Times.

The founders of the Yeltsin Center wanted the exhibition to be honest and objective.

"The Soviet system collapsed, and deciding what to build in its place was a tough decision. Not only was it important to feel the [nation's] pain and problems, but the situation required understanding of how to avoid the disaster of bloody redivision of the legacy … and how to create grounds for the new Russia instead of the burnt militarized Soviet empire," he said.

According to Burbulis, Russian officials embarked on falsifying and mythologizing Yeltsin's era in an attempt to restore their "imperial syndromes."

The very term "wild '90s" was invented by Putin, said Yuly Nisnevich, a professor of political science for the Higher School of Economics and former State Duma deputy from 1993-95. The term was first uttered at one of the pre-election congresses of the United Russia party, he told The Moscow Times.

"It's the leading idea that was voiced for propaganda reasons. … Because there must be an 'enemy' to fight," he said.

But it was just the historical period that was deemed an enemy, not Yeltsin himself, Nisnevich added. "The division is very simple: on one hand there are these '90s, a faceless [phenomenon,] and on other hand there's the president of the country. [He represents] authority, and authority is sacred in Russia," he said.

Putin has often expressed deep respect for his predecessor, at the same time pointing out the toughness of the decade during which Yeltsin had to rule, with his statements sometimes contradicting one another.

"Yeltsin, together with the new Russia, took on the path of tough, but necessary reforms. [He] led the process of drastic changes that drove Russia out of a cul-de-sac," Putin said in 2011, when Yeltsin's posthumous 80th birthday was celebrated all over the country.

Divided Society

Another event this year about the '90s that gripped public attention was a large festival called "The Island of the '90s," launched in September by the Colta.ru culture news website and supported by the founders of the Yeltsin Center. The festival took place at the central Muzeon park and was devoted to one of the most controversial periods of Russia's modern history.

Hundreds of Muscovites, nostalgic about the decade, attended lectures, round tables, movie screenings and concerts. The nostalgia was sparked several days before the festival, when Colta.ru launched a flash mob on social networks and called on users to post photos of themselves during the 1990s.

The practice quickly went viral — Russians of all ages started posting pictures and stories about their experiences. "We launched the festival to try and take a look at this terra incognita that the '90s suddenly turned into 15 years later," Maria Stepanova, editor-in-chief on Colta.ru, told the Kommersant FM radio station. "It was a time of huge trauma, huge shock," she said.

Although the flash mob itself didn't imply that "the wild '90s" were inarguably a good time, users who didn't share the nostalgia engaged in heated online fights with participants of the flash mob, trying to prove that 1990s were "wild" in the worst sense of the word.

"The goal [of the flash mob] is obvious: to play on the nostalgia and bring back … everything: devastation, decay, illegality, war, hunger," Ulyana Skoibeda, a pro-Kremlin columnist for the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper, wrote in her column at the time.

Surveys show that a lot of people hold a negative opinion about the beginning of the '90s, and their negativity is mostly related to way the country was governed, said Yelena Shestopal, head of the department of sociology and psychology of politics at Moscow State University's faculty of political science.

"As for the nostalgia that has been seen recently, it can be easily explained. We always consider that in our younger years everything was better: the sun was brighter and the grass was greener," she told The Moscow Times.

In addition to that, people always look for something to believe in, and, recalling the 1990s, they probably imagine some perfect model of life, she added.

Yeltsin himself rarely criticized Russia and its leaders after he retired. He only did so twice, according to his son-in-law Valentin Yumashev — for bringing back the Soviet national anthem in 2000 and for canceling gubernatorial elections in 2004.

As Yumashev said in an interview with the Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper, Yeltsin would likely not have been pleased with the current state of the country. "He [Yeltsin] would have thought that with the resources and opportunities that Russia has, with a favorable economic situation in the 2000s, Russia could have done more than it did," Yumashev said.

That was in January 2011, with Dmitry Medvedev in office as the third Russian president and Putin's successor, a few months before it became clear that Putin was coming back to the Kremlin. Since then, Yeltsin's relatives have avoided elaborating on what Yeltsin would have thought of any further developments in Russia.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.