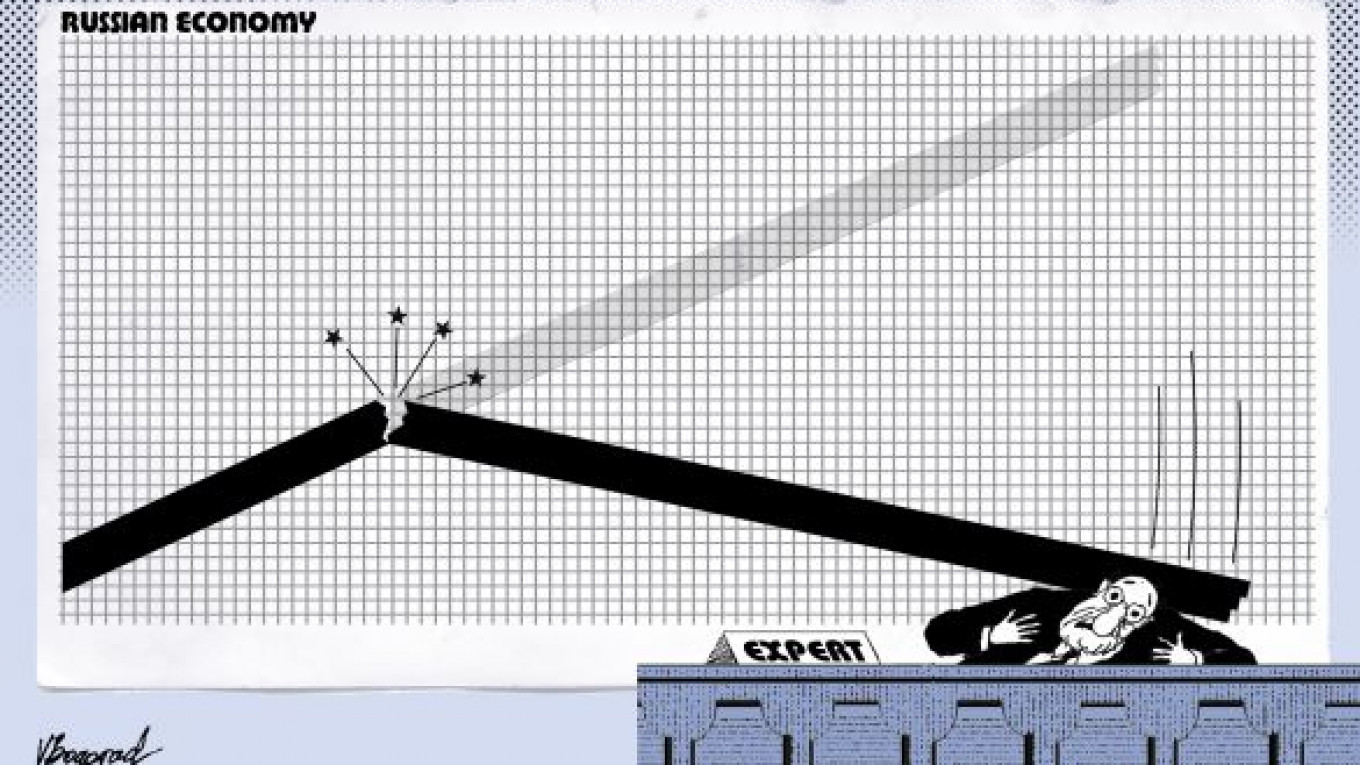

Contrary to earlier expectations, the Russian economy has been a surprising disappointment in terms of growth so far this year. The numbers are by now well-known. Growth has decelerated steadily from 2.9 percent in the third quarter of last year, to 2.1 percent in the fourth quarter, and then to 1.6 percent this year in the first quarter and down to 1.2 percent in the second.

We don't know the outcome of the quarter ending in September, and while some modest pick-up would be expected, it can hardly be assumed. For the year as a whole, a few weeks ago the Economy Ministry cut its growth forecast for 2013 to 1.8 percent from 2.4 percent last April.

And this deterioration follows a seeming trend of decline in Russia's economic dynamism in recent years from 4.5 percent growth in 2010, to 4.3 percent in 2011, and down to 3.4 percent last year.

As we can appreciate, Kremlin officials are beginning to feel a sense of panic. After all, it is not as if there is an obvious reason, external or internal, to explain this unexpected development. In fact, the sense of foreboding is greater because it seems to come as a surprise to analysts who projected growth of about 4 percent or so until recently.

For instance the International Monetary Fund in its latest world economic outlook issued last week now projects real growth in 2013 for Russia at a feeble 1.5 percent. Exactly two years ago it was projecting 4.0 percent. Even as recently as April 2013, the IMF still foresaw a 3.4 percent annual growth rate. For many, including me, this sudden weakening of the Russian economy through the first half of this year is a puzzle.

What is clear is that initially staid but steady expectations of reasonable economic growth have been confounded. The economy just keeps disappointing. Many analysts fear for the worst, pondering whether Russia may already be in recession.

On the one hand, it is contended, including by many in the Kremlin, that there is simply no margin left to squeeze growth out of the status quo economic structure. In their view, shared by many external observers, Russia is finally facing a long-term secular decline after many years of living well on high energy prices and Soviet era investments while avoiding any serious structural reform.

In this view, an off-putting combination of a declining work force, inadequate productive investment in the private sector, privileged state-controlled enterprises and banks, rampant corruption and a weak rule of law have finally culminated in inevitable decline. This structural interpretation leaves little hope for an easy way out.

If Russia is in such bad shape, it is not yet obvious in the numbers. According to the recent IMF data, the Russian economy is expected in 2013 to be the seventh largest in the world, having overtaken Italy earlier and Brazil this year. In terms of per capita gross domestic product converted into U.S. dollars, Russia's almost $15,000 is higher than in neighboring EU countries like Latvia and Poland.

So maybe Russia is just confronting a cyclical trough and better news is around the corner? After all, the IMF foresees a recovery to 3.4 percent growth next year, rising to 3.7 percent by 2018.

The problem is the data are ambiguous. For instance, stagnation would usually be accompanied by rising unemployment and declining real wages. This is not the case in Russia.

The unemployment rate, at 5.2 percent in August, is as low as it has ever been, reflecting a tight labor market. Real monthly gross wages rose by 12.8 percent from over a year earlier. Overall credit growth, while fortunately decelerating from the frothy levels of 2012, is still expanding at an annual rate of 18.5 percent as of September.

In fact, when the monetary policy committee of the Central Bank met last Monday, it noted, as did the IMF a week earlier, that economic output is now only slightly below its potential so there is no scope to add demand through a loosening of policy. However, it also seems that the Central Bank is reconciled to a future of relatively mediocre growth with no significant widening of the potential output gap. This view would be consistent with its chair Elvira Nabiullina's recent statement that long term trend growth may currently be around 2 percent to 2.5 percent.

So if the economy is operating at close to its potential and yet growth is almost stagnating, what can be done? It is clear that, in such circumstances, any temptation by the Kremlin to stimulate the economy would just add to overheating and a resurgence of inflation. It was just last week that the inflation rate was finally brought down to 6.0 percent on an annualized basis, the top of the Central Bank's policy range. Inflation remains the No. 1 concern of the population and there is little margin for stimulative policies.

In trying to at least comprehend the puzzle, maybe we can glean something from the IMF analysis about why all of the BRICS, after having been until recently the motor driving global growth, have all more or less simultaneously and unexpectedly slowed. Broadly, the IMF concludes cyclical factors have played a large, perhaps under-appreciated role. This could be seen as a cause for hope since it would be reassuring that the 2013 slow-down has been the result of cyclical, external factors rather than systemic internal problems.

More troubling is the conclusion that for Russia, as the IMF puts it, "time is running out on their current growth model." In other words, after flirting with cyclical causes, the IMF seems to align itself with the dominant structural decline thesis. In their view, the potential for future growth is not only subdued but likely to endure absent major policy changes.

So the Russian economy remains a puzzle, seemingly even to the IMF. Cyclical factors seem relevant, but they are not fully convincing and neither are the structural explanations. Is there a third possibility?

Economists are not necessarily good psychologists, but there is a promising sub-field of behavioral economics that may help shed light on what is happening. After all, a Nobel Prize was just awarded to a behavioral economist this week. Maybe when we put the Russian economy on the proverbial couch, we'll find that consumers and especially investors are suffering from the blues. When, and if, the mood changes, so will the economy.

Martin Gilman, a former senior representative of the International Monetary Fund in Russia, is a professor at the Higher School of Economics.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.