Russia's top psychiatric institution held an open house Wednesday in an attempt to popularize its work, amid speculation about a revival of Soviet-style punitive psychiatry following the sentencing of an opposition protester to mandatory mental treatment.

The Serbsky Center of Social and Judicial Psychiatry welcomed about a dozen journalists on an annual tour of its facilities, while trying to defuse suspicions of corruption in the medical evaluation of Mikhail Kosenko, a participant in last May's opposition rally on Bolotnaya Ploshchad that ended in clashes with police.

The state institution, which handles mental examinations of suspected criminals from across the country, had timed the tour to coincide with World Mental Health Day, marked Oct. 10.

But this year's tour was different, coming on the heels of the sentencing of Kosenko to indefinite hospitalization in a mental asylum at the recommendation of the Serbsky Center.

On Tuesday, a Moscow court convicted Kosenko, 38, who in his youth was diagnosed with a form of mild schizophrenia, of taking part in "riots" and attacking a police officer during last May's authorized rally on Bolotnaya Ploshchad.

The court sentenced Kosenko to indefinite mandatory psychiatric treatment despite the fact that he had never required such treatment in the past, prompting observers to speculate about the revival of punitive psychiatry applied to dissidents in the Soviet Union.

Yevgeny Makushkin, deputy director of the Serbsky Center, told journalists Wednesday that Kosenko had been "under treatment as it is" but still "committed a legal violation," which meant that the public danger of his actions had changed.

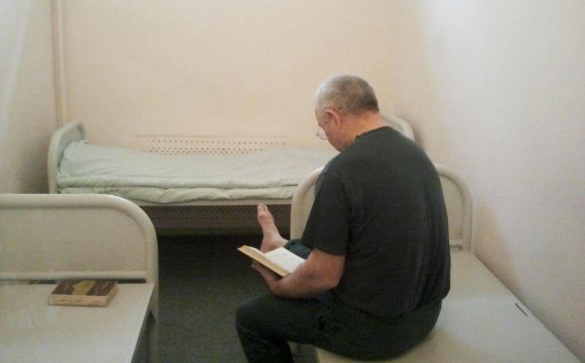

A patient reading in his room at the Serbsky Institute on Wednesday.

"If he is hospitalized, and doctors rule that he is no danger to society, then after six months doctors can address the court and, after medical measures are applied [to Kosenko], he will be released," Makushkin said during a tea party with journalists.

"How can you talk about punitive psychiatry here?" he said.

Speaking about corruption in psychiatry more generally, however, the center's director Zurab Kekelidze told journalists it was "possible, of course," adding that last year the center fired an expert "who took a bribe for his very first evaluation."

An independent service given a mandate of defending patients could provide protection from abuses by psychiatrists, said Sergei Shishkov, the center's top lawyer. He added that such a service was mandated by Russian law but did not exist, even though the center has long campaigned for its creation.

In an apparent attempt to make the center's work more transparent to the public, its management has been holding open houses for journalists for years.

This year, journalists were taken to the center's laboratories, wards and a museum. Behind the locked male wards with small glass windows in metal doors, patients in green pajamas lay on their beds reading or strolled aimlessly around the ward. One of them pressed his face against the window, gazing at reporters.

The acting head of the department responsible for the wards said that some of the patients barked and ate their excrement, and that she had been attacked by various patients on five different occasions over the course of her time working there.

"But it was my fault because I provoked them [to do so] with my questions," said Natalya, the department head. She refused to give her last name, saying she was not authorized to give official comments.

At the museum, journalists were shown items made by patients: small figurines made out of bread, a rope made from a cut-up mattress, nooses, handmade knives, slippers knitted from a blanket using pencils, and a bare wire used to boil hot water, among other things. Patients use nooses and knives to injure themselves or attack law enforcement officers.

"They seem to like people in white robes, but they do not like the convoy," said Zinaida Pugachyova, the museum's curator.

At a laboratory where sexual disorders are studied, a senior researcher told journalists about a "perversion when patients get sexual satisfaction from squeezing an orange."

Journalists were also offered condensed psychiatric dictionaries, which contained, among other terms, a list of unusual phobias, such as doraphobia — fear of animal fur, lacanophobia — fear of vegetables, and pantophobia — fear of everything.

Wrapping up the tour, the guide, Tatyana, a department head at the center who refused to give her last name for fear of being stalked by a former patient, welcomed journalists to return next year.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.