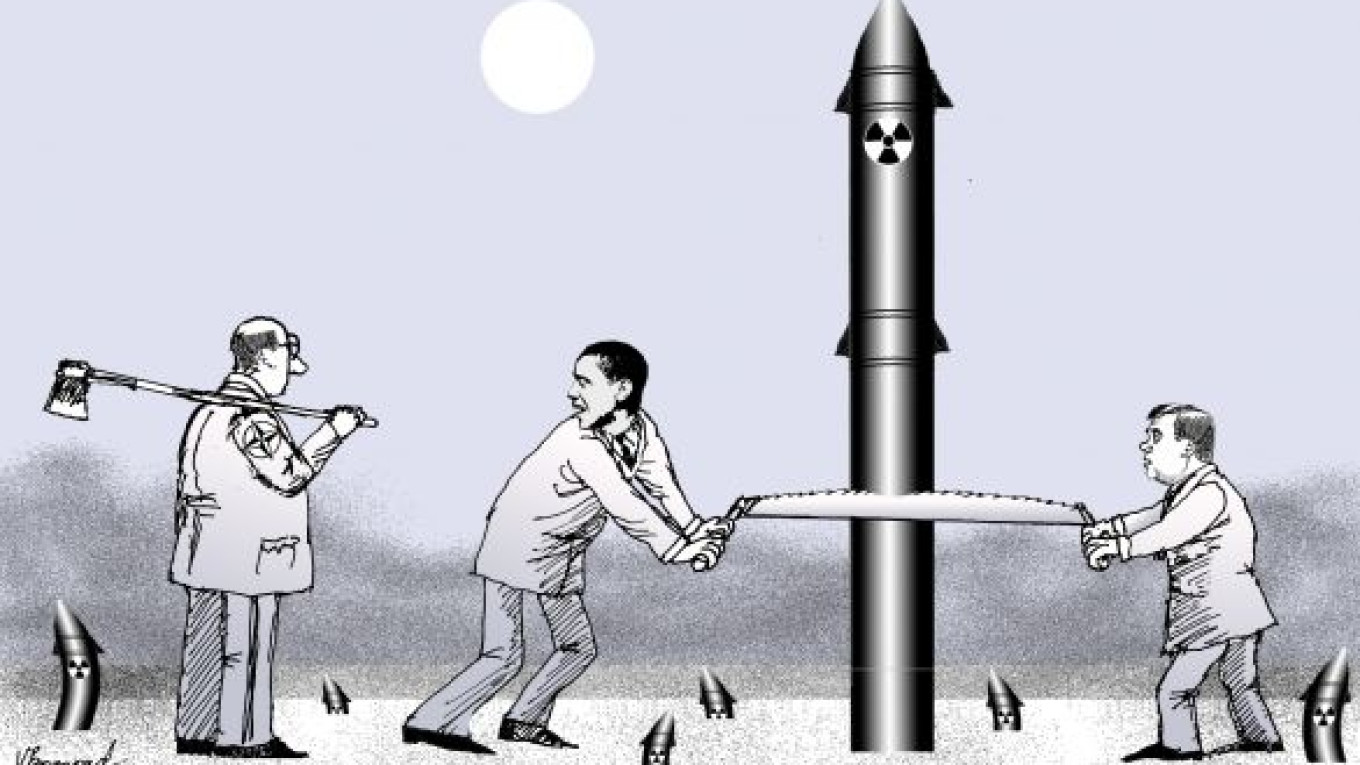

As the recent United Nations and Washington summits have demonstrated, nuclear arms control and disarmament are among the top issues on the world’s political agenda. They are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. Indeed, 2010 will determine whether U.S. President Barack Obama’s vision of a nuclear-free world will remain a distant but achievable hope, or must be abandoned.

No one should be under any illusions. Even if all of the world’s nuclear-weapon states embrace the vision of a world free of the threat of nuclear conflict, nuclear weapons will remain with us for two decades at least, and even that would require the most favorable conditions for disarmament.

This year is crucially important. The New START agreement signed in early April in Prague between Russia and the United States was accompanied by the publication of the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, identifying the nuclear capabilities that Obama’s administration wishes to preserve for the next four years. Many policymakers hope that 2010 will bring clarity on the North Korean and Iranian nuclear programs.

There are roughly 23,000 nuclear weapons today, which is 40,000 fewer than at the Cold War’s height. These weapons’ total yield is greater than 150,000 Hiroshima-size nuclear explosions. Nuclear disarmament is therefore still urgently needed, and prominent politicians in the United States and Germany have produced the U.S.-led Global Zero initiative and created the International Commission on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Disarmament, sponsored by Australia and Japan.

The United States, Russia, France, Britain and China — all signatories to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty — possess nine-tenths of the world’s nuclear weapons, while India, Pakistan and probably Israel possess about 1,000. North Korea presumably has a few, and Iran is most likely pursuing a nuclear-weapons program. Obama and President Dmitry Medvedev have agreed to reduce their strategic arsenals to 1,550 weapons each — far more than the 1,000 that Obama had in mind, but nonetheless a huge step that could bring about further cuts.

But the road to global nuclear disarmament will be long and bumpy. To begin with, the capacity to dismantle and destroy nuclear warheads is limited, and likely to remain so.

Second, there is the risk that other countries, particularly in the Middle East, will follow the example of North Korea and Iran. The International Commission on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Disarmament’s report “Eliminating Nuclear Threats,” released late last year, proposes meeting these challenges with a comprehensive agenda for reducing nuclear risks. As the German International Commission on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Disarmament commissioner, I believe that this report is the first and only one so far to suggest precise and feasible steps toward a nuclear-free world.

The report consists of 20 proposals to be decided on during the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty review conference in May and ends with proposed decisions to be taken after 2025. It leaves no room for doubt that a nuclear-free world is achievable without any risk to the security of individual states, provided that for the next 20 years or so there is sustained political will around the world, particularly in the nuclear-weapon states. In addition, the report proposes a declaration by these states that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons is to deter others from their use, coupled with an obligation not to increase their stockpiles.

For the 2025 time frame, the aim is to reduce the global nuclear stockpile to 2,000, or less than 10 percent of today’s total. A “No First Use” declaration should be collectively agreed upon, in conjunction with corresponding verifiable force structures, deployments and readiness status. As supplementary steps, the report suggests negotiating limitations on missiles, strategic missile defense, space-based weapons and biological weapons, as well as holding talks on eliminating conventional weapons imbalances.

Achieving this ambitious agenda by 2025 would usher in the last phase in the quest for a nuclear-free world, and requires, first and foremost, political conditions that reliably rule out regional or global wars of aggression. Nuclear weapons would thus become superfluous.

Only then could they be banned and their total elimination begin. In parallel, mandatory measures would penalize any states attempting to circumvent the ban, as well as individuals involved in producing nuclear weapons.

Obama’s vision could thus become reality 20 years from now, provided that the United States and Russia take the first steps this year. Immediate further cuts must include tactical weapons, with the few remaining U.S. nuclear weapons in? Europe withdrawn in exchange for the elimination of the still substantial Russian stockpile.

But the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe is by no means the first step toward nuclear disarmament. To suggest it as an opening move could damage European security and jeopardize trans-Atlantic cohesion, so the message has to be “no” to unilateral withdrawal, but “yes” to including these weapons in future arms-control negotiations. Withdrawal of these weapons would not mean the end of nuclear deterrence for Europe, as deterrence will remain necessary until the last nuclear weapon is dismantled. But the sole purpose of retaining some degree of deterrence will be to deter the use of nuclear weapons.

Europe perhaps benefited more than any other part of the world from nuclear deterrence because it helped preserve peace during the Cold War and prevented nuclear proliferation. But the time has now come to join Obama and Medvedev in bringing about disarmament. Indeed, without the U.S. and Russian examples, the world would see more, not fewer, nuclear-weapon states.

Klaus Naumann was chairman of the NATO Military Committee and chief of staff of the Bundeswehr. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.